- India

- International

In times of family grief, we become one and get tied to our unified selves

Our minds think about the beautiful things we have and that is family. It is the most valued institution where respect and honour are not performative. It is a candid space of attracting compassion and sharing warmth.

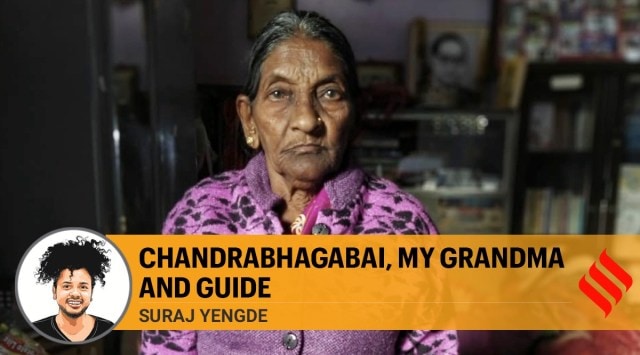

My grandmother, Chandrabhagabai, the common thread of our family passed away on January 4 at 9.15 pm in a civil hospital in Nanded

My grandmother, Chandrabhagabai, the common thread of our family passed away on January 4 at 9.15 pm in a civil hospital in NandedThis year started with grief for me. Having just bid farewell to what was the most difficult year for all, I wanted to look at 2021 with optimism. However, that optimism was to last a short while. My grandmother, Chandrabhagabai, the common thread of our family passed away on January 4 at 9.15 pm in a civil hospital in Nanded. She was suffering from asthma for the past quarter century of her life. She was battling exhaustion and had difficulty in breathing. The day she left us, she suffered a lot. She was on ventilator support. Her blood pressure was up and down.

My brother and uncle whose turn it was that night to attend to her sent me a photo of grandma from the ICU ward where she was admitted. The photo showed her lying on a torn, nylon government hospital bed with no sheets. This sight broke me. I was immediately drawn into depression. Nothing prepared me to see my grandma in that condition.

Before going to hospital, she hugged my mother and wailed, and asked her to take care of us – her grandchildren. My dad passed away six years ago; my grandma was crestfallen to see her eldest son — baba as she fondly addressed him — pass away in front of her eyes. Even though we are grown up and independent, a mother’s heart always looks at her children with love.

A week ago, I was told by my sister that aai’s health is serious. I immediately made a video call to her. Her face was swollen but at least she could stare into the screen and communicate with the help of my cousin. Aai had lost her ability to hear a few years ago. Her ears had become frail, and thus it was advised to not put any further pressure on it with a machine.

Chandrabhagabai’s children called her aai and the tradition continued with her grandchildren. Her ears grew accustomed to the melody of three boys addressing her as aai and later nine grandchildren adding chorus to that tune. Aai lived a satisfactory life. She saw her children and grandchildren grow into life size humongous people. She was four feet tall. Whenever we hugged her, we had to bend to allow her enough space to expand her arms like a giant eagle and take us into her. Once in, you felt safest. Her wrinkled skin was smooth like the stones in a flowing river.

Getting trapped into her hug meant at least a minute’s worth of embrace and bunch of embarrassing kisses. She kissed us like she did when we were toddlers. I always wondered how she felt when she saw us, her grandchildren, who had grown into larger size beings. Seeing me at a noticeable height, she began to address me as “saheb”. Earlier, she called me “balla”. She would also address me with honorifics such as “tumhi” or “aap” in Hindi. This came to her naturally as someone who had grown to genuflect or act as subordinate to a slightly educated, higher authority. The story of Chandrabhagabai, my aai is emblematic of the lives of the elderly Dalit generation.

Our family is unsure of the year of Chandrabhagabai birth, let alone date or month. The closest guess is 1940, if assessed through her children’s age. She was born to a family of landless labourers, Hanumante. She was disciplined into the caste codes early on. “We were taught not to touch the food and water pots of the higher castes”, grandma reminisced. “We were never given water with respect. They would pour the water from top.” Grandma worked as a child labourer in the fields of Maratha landowners. Her family would make 25 paise per day during the harvest season. She never went to school.

Chandrabhagabai was older than her two brothers and younger than her sister, and like many sisters she virtually brought her brothers up. Along with her husband, the handsome mill worker comrade who toiled in the Usman Shahi Mill in Nanded, she lived on the peripheries of semi-urban life in a ghetto of Dalit labourers. The couple had a makeshift room without a door. A plastic cover acted as a wall and the door was made of dry twigs.

Chandrabhagabai had three boys and worked odd jobs to raise her family. She worked in farms, in a shoe factory, as cook in a hostel for Dalit students. Working in a congested room, cooking three times a day for an entire hostel, took a toll on her health. But she had to slog it off. She did it for her children. Poverty was an inheritance for her but aai never compromised on wearing a clean saree (lugda). Her beauty was unsurmountable. Yet, she remained a victim of toxic patriarchy in which every Indian girl is married into..

Once, Chandrabhagabai’s story or a tribute to her life by her grandson, that too in English, would not have made it to international press. This is a marvel for the Dalit community, a rare sight indeed.

She comes from a community of great people, yet the lowest class outcastes, who dared to dream bigger than their immediate reach, time and life. For Dalits, our ancestors are our gods. It is upon their lives that we build on further. Aai has joined the pantheon of our ancestors to guide us through her spirit, and act as an example of faith, tolerance, integrity, and tight love.

I write this as a tribute to all the grandmothers and grandfathers whose strong love and fortitude has made possible for their grandchildren to strive for something more than what was inherited as a moral value.

To those who lost their loved ones in the recent past, I mourn with you. Our losses are irreplaceable, but we should always think about the good moments we had with the departed souls. After all, what remains is memory. The repository of good memories is what will keep us moving. There should be public platforms to share the phases of mourning. Let it be a collective mourning exercise. We should acknowledge the fundamental truth to life that no one has been able to alter — death. To work with death as a finality, we can find peace in the essence of life. We should learn to embrace death that guides the Buddha’s enlightenment. My grandma was born as an untouchable but she died a Buddhist.

To allow empathy to soothe our roughened mind, we need a contentment in our inner self. In times of family grief, we become one and get tied to our unified selves. Our minds think about the beautiful things we have and that is family. It is the most valued institution where respect and honour are not performative. It is a candid space of attracting compassion and sharing warmth. This is a feeling we all need to share with each other as we prepare for transcendence.

This article first appeared in the print edition on January 10, 2020 under the title ‘Chandrabhagabai, my grandma and guide’. Suraj Yengde, author of Caste Matters, curates the fortnightly ‘Dalitality’ column

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05