- India

- International

For Operation Green to deliver, experience of raising milk production in Operation Flood can prove beneficial

A closer examination of the scheme in terms of achieving its objectives of price stabilisation, reveals that Operation Green is in slow motion, and nowhere near achieving its objectives.

The announcement to create an additional 10,000 FPOs along with the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund and the new farm laws are all promising but need to be implemented fast.(Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

The announcement to create an additional 10,000 FPOs along with the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund and the new farm laws are all promising but need to be implemented fast.(Illustration: C R Sasikumar)While presenting the Union budget for the FY 2021-22, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that Operation Green (OG) will be expanded beyond tomatoes, onions, and potatoes (TOP) to 22 perishable commodities. Although we don’t know yet which other commodities have been included in OG, we welcome this move as it reflects the government’s intentions of creating more efficient value chains for perishables. Operation Green was originally launched in 2018 by the late Finance Minister Arun Jaitley. It has been now three years, and it may be useful to see how it has progressed so far, and whether it has achieved its objectives. Based on this rapid appraisal, one can suggest what else needs to be fixed to ensure that it delivers quickly and effectively as it expands to cover 22 commodities.

There were three basic objectives when OG was launched. First, that it should contain the wide price volatility in the three largest vegetables of India (TOP). Second, it should build efficient value chains of these from fresh to value-added products with a view to give a larger share of the consumers’ rupee to the farmers. And third, it should reduce the post-harvest losses by building modern warehouses and cold storages wherever needed.

The design and strategy followed so far are that the OG scheme is housed in the Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MoFPI) under a Joint Secretary. MoFPI has invited some programme management agencies to see its implementation. Out of the Rs 500 crore from its initial outlay, Rs 50 crore were reserved for the price stabilisation objective, wherein NAFED was to intervene in the market wherever prices crashed due to a glut, to procure some excess arrivals from the surplus regions to store them near major consuming centres. Another Rs 450 crore has been reserved for developing integrated value chains projects. Such projects are given 50 per cent grants-in-aid with a maximum limit of Rs 50 crore per project. This subsidy goes up to 70 per cent in case the project is of a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO). As of February 23, six projects worth Rs 363.3 crore have been approved for the scheme, of which Rs 136.82 crore has been approved as grant-in-aid. But so far, a mere Rs. 8.45 crore has been actually released, which may be because the scheme envisages the payment of subsidy on a reimbursement basis.

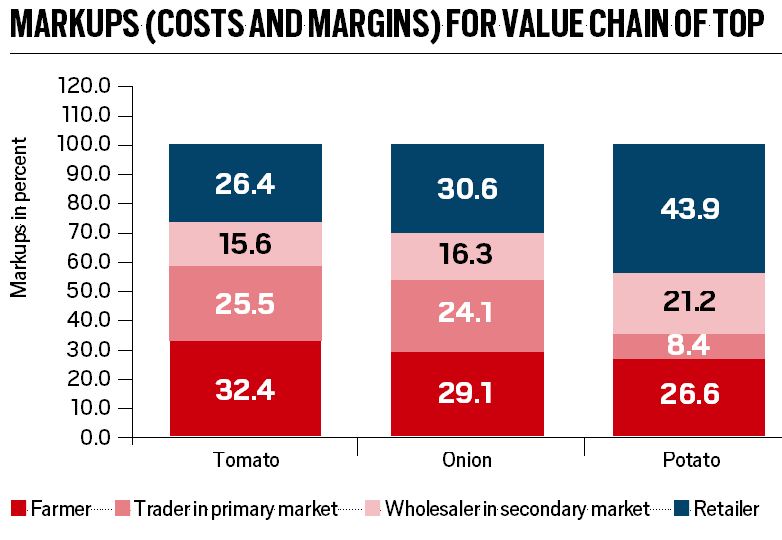

A closer examination of the scheme in terms of achieving its objectives of price stabilisation, or ensuring a larger share of farmers in consumers’ rupee, reveals that OG is in slow motion, and nowhere near achieving its objectives. Our research at ICRIER reveals that price volatility remains as high as ever, and farmers’ share in consumers’ rupee is as low as 26.6 per cent for potatoes, 29.1 per cent in the case of onions, and 32.4 per cent for tomatoes (see graph). This is reflective of the malaise in the horticulture sector.

Graphic: Ritesh Kumar

Graphic: Ritesh Kumar

In contrast to this situation in the horticulture sector, in the milk sector. In cooperatives like AMUL, farmers get almost 75-80 per cent of what consumers’ pay. Operation Flood (OF) transformed India’s milk sector, making the country the world’s largest milk producer, crossing almost 200 million tonnes of production by now. Although OG is going to be more challenging than OF — each commodity under OG has its own specificity, production and consumption cycle, unlike the homogeneity of milk as a single commodity — there are some important lessons one can learn from OF.

First and foremost is that results are not going to come in three to four years. One has to be patient. OF lasted for almost 20 years before milk value chains were put on the track of efficiency and inclusiveness. If this is the horizon needed for OG, we need a different structure and strategy than is being followed currently. There has to be a separate board to strategise and implement the OG scheme, more on the lines of the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) for milk, which keeps itself at arm’s length from government control.

Second, we need a champion like Verghese Kurien to head this new board of OG — a leader who is respected for his/her independence, as well as commitment and competence to give a different shape to horticulture sector value chains. That person will have to be given at least a five-year term, ample resources, and be made accountable for delivering results. The MoFPI can have its evaluation every six months, but making MoFPI the nodal agency for implementing OG with faceless leaders (joint secretaries who can move from one ministry to another at the drop of a hat) is not very promising.

Third, the criteria for choosing clusters for TOP crops under OG is not very transparent and clear. The reason is while some important districts have been left out from the list of clusters, less important ones have been included. For example, Nashik, a well-known tomato-growing region, with one of the largest tomato mandis in Pimpalgaon, has been left out, while less important districts from states like Odisha (Kendujhar and Mayurbhanj), Gujarat (Sabarkantha, Anand and Kheda) and West Bengal have been included. Similarly, Nalanda in Bihar was included in the onion cluster, but Aurangabad district in Maharashtra, (which is an important white onion growing region) was left out. For potato, Punjab was finally included after Chief Minister Amarinder Singh requested the addition of districts from the state as clusters. What is needed is quantifiable and transparent criteria for the selection of commodity clusters, keeping politics away.

Fourth, the subsidy scheme will have to be made innovative with new generation entrepreneurs, startups and FPOs. The announcement to create an additional 10,000 FPOs along with the Agriculture Infrastructure Fund and the new farm laws are all promising but need to be implemented fast.

This article first appeared in the print edition on March 1, 2021 under the title ‘A project of slow motion’. Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor and Wardhan a consultant at ICRIER

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05