The day former UK prime minister David Cameron popped in must have been an odd one in the little office inhabited by the 15 or so employees of The Bond & Credit Co, a small insurance business run out of the 14th floor of a nondescript office building in Sydney.

But industry sources say that while he was there the former UK prime minister saw someone very important to the globe-spanning financial empire put together by his friend, former Queensland sugar farmer Lex Greensill.

That person was Greg Brereton, an insurance executive who worked with Greensill Capital.

Until recently, Brereton was a relatively unknown figure in an obscure industry, trade credit insurance.

But he has been identified as being responsible for writing billions of dollars in insurance that helped turn the gears of Greensill Capital’s complex financial engine.

In early March, documents released by a Sydney court included the allegation he went too far in servicing the finance group’s need for insurance.

The documents were tendered to the New South Wales supreme court as part of an application Greensill Capital made for an order forcing its insurers to renew $4.6bn in policies covering loans the group made to its customers. Greensill Capital was unsuccessful and the insurance lapsed.

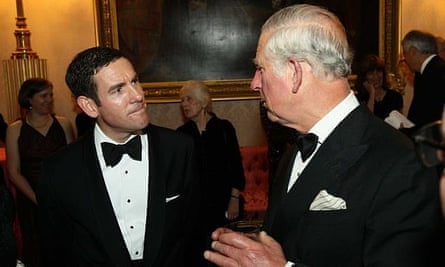

It is not clear what the purpose of Cameron’s visit was in 2018 although it is public knowledge that he was one of Greensill Capital’s advisers. There is no suggestion of wrongdoing with respect to that visit or the meeting between Brereton and Cameron.

But other questions have been left hanging following the collapse over the past fortnight of Greensill Capital, which is now under the control of administrators in the UK and Australia.

The unwillingness of The Bond & Credit Co’s owner, large Japanese insurer Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance, to extend some of the policies that Brereton was identified as having written has emerged as a prominent factor in the collapse.

Tens of thousands of jobs are now at risk at Greensill Capital’s corporate clients, which relied on it for finance to pay their suppliers.

Its biggest single client, GFG Group, owned by British businessman Sanjeev Gupta, is racing against time to refinance some $4bn it owes Greensill Capital so that it can avoid a failure that could devastate communities that depend on steel mills it runs in Britain and Australia.

It’s not the outcome Lex Greensill was hoping for – until recently he was hoping to raise more than $500m by floating the company on the stock exchange, a move that would have valued it at more than $7bn.

Now, it will be up to administrators from the accounting firm Grant Thornton to figure what, if anything, the insolvent empire might be worth to bargain-seeking buyers.

Supply chain financing

Lex Greensill wasn’t always a financial engineer. He started out in the family business, sugar farming.

He and his family own thousands of hectares of land near Bundaberg, north of Brisbane, where they farm sugar, the region’s main crop, and sweet potatoes.

Greensill Capital’s operational centre is in London, but the parent company of the group remains an Australian company, registered to one of the family’s farming facilities outside Bundaberg.

The family has been growing sugar cane for three generations, starting with a small crop, planted and cut by hand, in 1945.

But these days Greensill Farming bills itself as a large agribusiness that uses “innovative practices to achieve sustainable farming for future generations to come”.

It was on this farm that in 2016 Greensill and Gupta came up with a plan to finance Gupta’s bid to rescue the Whyalla steelmill from the wreckage left behind by the collapse of Australian mining group Arrium, according to a 2018 profile of Greensill in the Australian newspaper.

“I’m a farmer at heart. And I love it here,” Greensill reportedly said of the farm. “Whilst I think I’m blessed to be able to run our financial services company, in my heart I will always be and want to be a farmer.”

Until recently, he was a farmer with a fleet of four private planes that would sometimes touch down at Bundaberg’s single-runway airport.

The jets are gone now, sold in November as part of efforts by Greensill Capital to make itself more attractive to would-be investors. Until then, they had been a symbol of the fast growth enjoyed by the finance group since Greensill founded it in 2011. As it grew, it attracted well-connected advisers to smooth its way – in the UK, Cameron, and in Australia, former foreign affairs minister Julie Bishop, who quit the role in the past few weeks.

His burgeoning empire also helped pay for a vicarage in the Cheshire village of Saughall, which he renovated into an eight-bedroom mansion, and earned him a CBE for services to the British economy in 2018.

Greensill Capital’s core product was something known as supply chain financing, or reverse factoring. What it amounts to is lending money to large companies to help them pay their suppliers. It’s a little like payday lending, but for the big end of town.

For cash-hungry corporates, it’s a sugar hit that immediately frees up money. In Australia, clients included blue-chip companies such as Telstra and the contractor CIMIC, which were always capable of paying their suppliers.

But the ratings agency Moody’s says getting hooked on supply chain financing can be dangerous for less financially solid companies. It lays some of the blame on the practice for the collapses of the UK government contractor Carillion, which failed in 2018 owing about £1bn, and Abengoa, a Spanish renewable energy company and Greensill Capital customer that imploded in late 2015 owing banks €20.2bn.

“Supply chain finance is very addictive for companies, because you pay later and later and later,” an industry source says.

Small business and Australia’s opposition Labor party have also attacked the use of supply chain financing to push out payment times to suppliers.

In 2019 Lex Greensill told Guardian Australia the use of the product was “completely optional” for suppliers and that he urged companies to pay on time.

At the time, Greensill Capital’s business model was already under fire from some, especially financial media in the UK.

It was complex enough that Greensill himself couldn’t explain how the UK operating entity was booking solid revenue despite having negative cash flow – “I honestly don’t know what the answer to that is,” he told Guardian Australia. (Greensill executives later explained the difference.)

Nonetheless, Greensill was full of expansion plans. He had just met the Australian prime minister, Scott Morrison, with a view to lending to public servants against their next pay packet.

The proposal never got off the ground, but Greensill Capital’s corporate customers kept coming back for more. Greensill Capital made loans worth more than $140bn in 2019, and about the same again last year, despite the pandemic.

The financial apocalypse

Of course, the money Greensill Capital loaned out was not its own. Ultimately, it came from investors in funds run by Credit Suisse in Luxembourg.

The biggest of these, with an estimated US$5bn in it, was a sub-fund of a Credit Suisse fund called Virtuoso, which is believed to have invested heavily in loans to GFG companies.

To make itself more attractive to investors, the fund took out insurance that would pay out if the Greensill Capital customers it ultimately loaned its money to defaulted. No matter how bad the customers turned out to be, the insurance company would be good for the money.

This feat of financial alchemy, comparable to the way mortgages were packaged up and sold before the global financial crisis, transformed GFG’s rickety steel mills into investment-grade gold.

But at midnight on 1 March, the spell was broken when insurance on $4.6bn in Greensill Capital loans written by Brereton expired.

The crisis had been in the works for some months. TBCC’s owner, Tokio Marine, first flagged problems with the policies Brereton had written for Greensill Capital on 2 July last year, documents tendered to the NSW supreme court show.

In an email to Greensill Capital’s insurance agent, Mark Callahan, a Tokio Marine executive based in Houston, Texas, said Brereton’s ability to write insurance was reduced a month earlier. He said the company would not be writing any new insurance for Greensill, or extending existing policies, until further notice from Tokio Marine’s Australian managing director, Toby Guy.

On 4 August, Guy, in his capacity as a director of TBCC, wrote to Lex Greensill and Markus Nunnerich, a director of a bank Greensill Capital owns in Germany, to tell them that TBCC was investigating more than $10bn in insurance Brereton wrote over Greensill Capital loans between June 2019 and July 2020.

This is about 7% of the total loans made by Greensill Capital in a year.

In the 4 August letter, Guy alleged that some of the insurance policies lacked supporting paperwork, including proposal and transaction documents as well as monthly reports on their status.

Brereton has not responded to efforts to contact him via LinkedIn.

TBCC formally advised that the insurance would not be renewed in a notice sent to Greensill on 1 September.

Inside Greensill, executives knew the company was in trouble. Company documents show that Greensill Capital engaged the London office of the accounting firm Grant Thornton on 31 December to provide “contingency planning which included conducting supporting analysis in relation to the options and financial outcomes available to the companies as they sought to restructure”.

But despite knowing for months that the insurance was going to run out, Greensill Capital did not launch legal action seeking to force its renewal until after business hours on 1 March – just hours before the two policies at the centre of the case were due to expire.

Nor did it find another insurer to take on the risk – even though it’s understood TBBC was just one of about 20 insurance companies Greensill Capital has used.

Once the insurance fell away, European regulators swooped.

On 3 March, German regulator BaFin temporarily shut down Greensill Capital’s bank, saying there was “an imminent risk that the bank will become over-indebted”.

As a result of the insurance lapsing, Credit Suisse suspended the funds that pumped money into Greensill Capital’s engine.

It also took action in Australia to secure a separate $140m loan to Greensill Capital, by appointing receivers over the company in Bundaberg that sits atop the group.

Confronted with the financial apocalypse, Greensill Capital’s directors, including Lex Greensill, handed over control of the group to administrators from the accounting group Grant Thornton.

Before the collapse, Greensill Capital had been negotiating to sell all or part of itself to private equity group Apollo. That now seems less likely, although after sifting through the wreckage the administrators may find some parts of the group that may still be of some value.

The fate of Gupta’s steel empire also now hangs in the balance. It is in dispute with Greensill Capital over the debt, on which Greensill Capital claims it has defaulted, but says it has “adequate funding for our current needs” as it looks for a new backer.

Some are sceptical Gupta can make it happen and fear a collapse that could wipe out more than 30,000 jobs in Australia and the UK.

“How does he survive and prosper when his business is based on supply chain financing, which I call payday lending,” a source with knowledge of GFG’s Australian operations says.

The source says one bright spot was that the Whyalla mill, which GFG has been trying to transform into a producer of green steel, was “making money for the first time in a long time”.

“Sanjeev has just staked so much of his personal credibility on Whyalla, and he’s done that globally,” the source says. “If it all becomes a farce and it all goes to shit, that’s a different prospect.”

Keeping the farm

Murray Ironfield, TBCC’s former head of risk, declined to answer questions about the Greensill insurance.

“I was peripheral to that business at that stage in 2018-19,” he says.

Ironfield says those questions are for Guy, who did not respond to emails. Tokio Marine also declined to answer detailed questions, but a spokesman said: “Tokio Marine has examined in detail the group’s relationship with Greensill and can confirm that no changes to the group’s 2020 financial forecast are necessary and that existing guidance remains unchanged.” Greenskill declined to comment on the allegations made in court documents against Brereton.

Whatever happens, it looks as though Lex Greensill will be able to keep that farm he loves so much.

Guardian Australia understands Greensill and its creditors have no claim over the Bundaberg operation and Greensill’s spokesman says the farming business “operates entirely independently of Greensill Capital”.