The passengers on Tien Pham’s 15 March flight were scared and anxious. Some were distraught or in denial. Many seemed lost.

In the months leading up to his deportation, Pham, a 38-year-old California resident, had held out hope that he’d be able to stay in the country his family had called home since he was 13. But when he saw the 30 other Vietnamese Americans who would be flying with him from Texas to Vietnam that day, he knew it was over.

“I tried to accept it. I told myself to just look forward, don’t look back,” Pham recalled three weeks later from his cousin’s apartment in Ho Chi Minh City.

Pham is one of thousands of people who have been deported by Joe Biden’s administration.

Biden has pledged to undo Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda and deportation machine, and has issued some initial executive orders reining in US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice). But in his first 100 days, he also maintained a controversial Trump-era rule to immediately expel the majority of people apprehended at the border and indicated he’d keep a historically low cap on refugees, before moving to lift it after public outcry. His deportation policies, focusing on people considered a “threat” to society, have continued to sweep up refugees with old criminal records like Pham, even after their home states have ruled that they posed no danger to public safety.

Surviving a childhood of violence

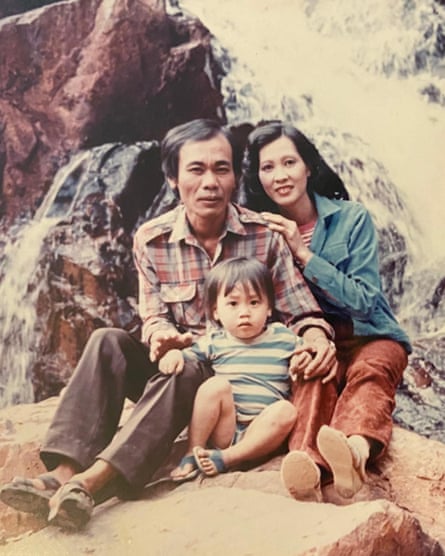

Pham’s memories of Vietnam are largely violent. Born in 1983, he grew up in the aftermath of the Vietnam war. His father had served in the South Vietnamese army alongside the US, and ended up imprisoned in a “re-education” camp where he was forced to work and ate rodents to survive.

His family, originally from north Vietnam, stuck out in Ho Chi Minh City and his parents warned him to stay home as much as possible: “Every time I went outside or went to school, I was a target,” Pham said. “The environment was very violent and corrupt.” At age 12, he said, he was brutally beaten and robbed.

Pham was relieved when his family came to California in 1996 as refugees, resettling in a low-income housing project in San Jose. But he struggled with English and fell behind in class, despite excelling in school in Vietnam: “I was embarrassed and humiliated,” he recalled.

Facing bullying and violence in his school and neighborhood, he got involved in local street gangs, which offered him protection – a common story of south-east Asian refugees who grew up in poverty in California.

His parents worked long hours in low-wage jobs to stay afloat, and were often unaware of his struggles, which included drinking at a young age. In 2000, at age 17, Pham got in a fight with other youth, and he and a friend were accused of stabbing and injuring someone. Pham was arrested, prosecuted as an adult and convicted of attempted murder. Under harsh sentencing laws, he was given 28 years.

“He looked really young back then,” recalled Chanthon Bun, a Cambodian refugee who was incarcerated at the same prison 20 years ago and became like a big brother to Pham. “He was intimidated. I showed him how to navigate prison, how to keep safe.”

Bun and Pham motivated each other over the years to stay productive, and opened up about their parallel childhoods. “We spent a lot of time unraveling our trauma,” Bun said. The duo would often joke around to make prison more bearable, Bun said. “We grew up incarcerated together.”

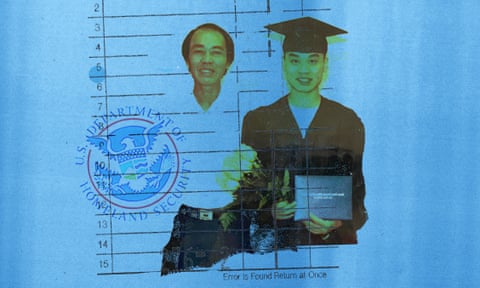

Pham received multiple educational degrees and certifications, helped teach an ethnic studies program and worked for a prisoner-run newspaper.

Pham was granted parole last June after the passage of new laws that acknowledged the harm of lengthy sentences for children. Multiple community groups had pledged to support his re-entry, he had strong endorsements from prison staff and the governor approved his release.

On the morning of 31 August, the day of his scheduled release, Pham’s family was waiting for him outside the San Quentin prison north of San Francisco, ready to take him home for the first time in two decades. But Pham never came.

“We thought we would all be joined again at our family dinner table,” said Tu Pham, Tien’s 74-year-old father, in an email in Vietnamese, translated by his daughter. “We had always believed America is a land of hope … Things were hopeful until the day we were expecting Tien at the ‘freedom’ gate only to see him nowhere in sight.”

‘We thought America was the land of hope’

Pham was one of an estimated 1,400 people who the California prison system transferred directly to Ice agents at the end of their sentences last year. Gavin Newsom, the Democratic governor, has faced intense scrutiny for this policy of voluntarily handing foreign-born state prisoners to Ice for deportation, which advocates say is a form of double punishment.

Pham was also due to be released at a time when San Quentin was battling a catastrophic Covid-19 outbreak, and he and his family were hopeful that the prison would let him go home, rather than risk spreading Covid to an Ice detention facility. They were also optimistic because Bun, also a refugee, had been released from San Quentin two months before Pham, and was not transferred to Ice.

The two planned to eat Korean barbecue, visit the beach and go fishing once they were both free. But on Pham’s release date, a van arrived at the prison that he quickly recognized as an Ice vehicle.

Pham thought of the stories he had heard of people stuck for years in Ice detention while fighting their cases: “I didn’t want to spend any more time being locked up, and not knowing how long I was going to be there weighed very heavily on me.”

Once in Ice custody, Pham’s green card was revoked. Over the next six months, Ice shipped him across the US – to Colorado, back to California, then to Arizona, Louisiana and Texas.

In February, under the new administration, Pham’s attorney requested humanitarian parole, but Ice responded with a blanket denial. Despite a public campaign to halt the deportation of Pham and other Vietnamese refugees, he was flown away in March.

Thousands deported under Biden

In February and March, Biden’s first two full months in office, Ice deported more than 6,000 people, according to data provided by the agency. That marked a sharp decline from the Trump administration, which was deporting roughly twice as many people per month and pursued removal against anyone in the country without authorization.

Biden had initially announced a 100-day pause on deportations, but the policy made exceptions for people considered a “danger” to national security. A judge ultimately blocked the moratorium weeks after its introduction.

“Ice’s interim enforcement priorities focus on threats to national security, border security and public safety,” a spokesperson said in an email.

But those priorities still ensnare vulnerable immigrant communities, including refugees who were criminalized as children under outdated tough-on-crime laws championed by then-senator Biden. Some asylum seekers were also being sent back to regions where they face severe violence, advocates say.

The Asian Law Caucus (ALC) and other California groups have been fighting for Gabby Solano, a domestic violence survivor who spent 22 years in prison and who the Biden administration is seeking to deport to Mexico. ALC activists said they were especially frustrated to see Biden deporting large groups of Asian refugees in the same week he condemned anti-Asian violence.

Advocates also argued that felony convictions should not be justification for deportation. “They are framing the deportation policy as a public safety policy – that they are deporting people who are an ‘imminent danger’,” said Anoop Prasad, ALC staff attorney who represented Pham. “But we see that is not true. California is releasing people on parole having explicitly found they do not pose a danger … and then still hands them over to Ice to be deported.”

On his flight to Vietnam, Pham tried to comfort the people around him, including some who he said barely spoke Vietnamese and had lived in the US for decades. Some were recently picked up by Ice and appeared in denial: “They were really lost … They have families and businesses and properties they are leaving.”

He and others were, however, relieved to be out of Ice custody, where he said they had not been given an opportunity to get vaccinated and had recently encountered another detainee infected with Covid.

‘I just want to hug my parents’

Pham may never be able to come to the US. His deportation order, in effect, constitutes a lifetime ban, Prasad said, unless the California governor would move to pardon him.

Meanwhile, advocates are campaigning for a proposed California state law that would end transfers from prisons to Ice and save people from deportation – and urging Biden to exercise his discretion and not deport people based on convictions.

In Ho Chi Minh City, Pham said it was overwhelming to adjust to being free for the first time since he was a teenager, while also being exiled thousands of miles from his family. He has been able to visit some relatives in Vietnam, but said Ho Chi Minh City felt largely unfamiliar. He did, however, recognize the corner where he was assaulted as a 12-year-old.

Pham might pursue teaching English, though for now is still just getting accustomed to technologies he never used behind bars.

Pham’s family hopes to travel to Vietnam, but his father has recently fallen sick.

“I pray every day for Covid restrictions to be over and that I would be strong to beat my poor health so that I can hopefully see Tien again,” his father told the Guardian. For now, he added, “We continue to see Tien over a screen.”

Pham said it was hard to think that his family reunification in California would never come to pass.

“I pictured it so many times … I always felt that America is my home. My family, my loved ones, my friends, they are all there,” he said, adding, “I just wanted to give my parents a hug and tell them, ‘Mom and Dad, I’m home.’”