With the golden winter sun slanting across the palm trees and yellow sandstone, the scene was perfect. Emmanuel Macron and his host, Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, walked down the red carpet of the Union buildings in Pretoria as the Marseillaise resonated through the clean, crisp air.

The historic setting was apt. Since taking power in 2017, the French president has sought a broad reset of national strategy, relations and intervention in Africa. He has chosen a very contemporary way to do this: by re-examining the past.

In Africa, he is not alone in regarding history as important. Last week Germany agreed to pay Namibia €1.1bn (£940m) as it officially recognised its colonists’ murder of tens of thousands of Herero and Nama people at the start of the 20th century – a gesture of reconciliation, but not legally binding reparations, for what Berlin now recognises was a “genocide”.

Others also see the history of the continent as critical – and useful – today. China, which has made a major effort to extend influence across Africa, systematically highlights the bloody past of western colonial powers on the continent. Russia has consciously invoked the relationships and myths of the cold war, telling countries such as Angola that the former ties bind tight.

Britain has tried to invoke imperial history through the Commonwealth, in the somewhat optimistic belief that leaders and citizens of former colonies will remember fondly decades of exploitative and sometimes brutal rule. So far this appears to have had little success. Early efforts to restore Zimbabwe to the Commonwealth have foundered and the government in the troubled former British colony recently unveiled a statue in the centre of the capital, Harare, of a revered spiritual leader who resisted subjugation by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa company.

“It’s true that France has a history in Africa that is complex,” said Hervé Berville, a French member of parliament who accompanied Macron. “Sometimes of happiness, of family, a wealth of cultural and other exchange, but more complex, deeper, heavier too. And we have to recognise our wrongdoings, our mistakes … This is not to self-flagellate but simply to be honest with ourselves and others who have lived the consequences of our actions.”

On Thursday, the French president spent a day in Rwanda, a former Belgian colony whose government has long accused France of complicity in the killing of about 800,000 mostly Tutsi Rwandans in 1994.

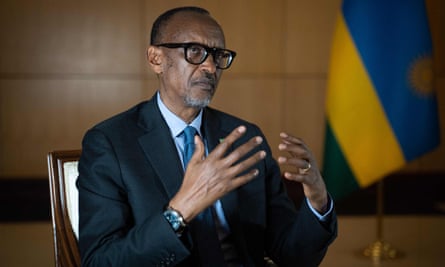

In Kigali, Macron asked for forgiveness and spoke of how the French bore a terrible responsibility after standing by a genocidal regime for far too long – though he said it had the best of intentions. The speech was based on the findings of a French report by historians and archivists given unprecedented access to key French government archives. Though not an apology, Macron’s words were enough to satisfy Paul Kagame, in power in Rwanda for 27 years and one of the most influential leaders on the continent.

“By recognising the errors of our past [in Africa], we can better prepare our future there,” said Berville, an orphan evacuated by the French army from Rwanda who grew up in France. Another benefit is pre-empting the efforts of competitors such as Russia or China from “instrumentalising and exploiting” that history.

A similar historical inquiry investigated atrocities committed by French authorities, police and troops in Algeria during the colonial period and bloody war of independence there. Then there are moves to repatriate at least some of the works in French museums that were looted from Africa.

Mohamed Diatta, an analyst at the ISS in Pretoria, said Macron had been inconsistent but appeared to have recognised the importance of the past in opening up new opportunities to engage with Africa’s young population.

“There is a little bit of movement and it is encouraging. France’s ultimate guiding principle is protection and advancement of its own interests, that’s not going to change, but the way they do things can change,” said Diatta. “France’s relationship with Africa … cannot be separated from how France is dealing with its colonial past in France itself; how France deals with its immigrant population of African descent in France. There is this past that needs to be addressed in a proper manner.”

But some aspects of the past can also be usefully ignored. Macron’s new strategy sees the continent as an immensely varied whole, not divided by old empires or language, with opportunities for political or economic advantage well outside the traditional “FrançAfrique”. Analysts point out that South Africa, a former British imperial dominion where English is the primary language of business and administration, is not a traditional partner of Paris.

“France recognises there is an advantage in non-French-speaking parts of Africa that don’t have the hang-ups and suspicions of FrançAfrique and so is making a bigger push there,” said Alex Vines, director of the Africa programme at Chatham House. “There are historical relationships with former colonies but it’s not there that its businesses are making money and making inroads.”

Critics point out that there is much that looks still familiar about French interventions. Security, arms sales and resource exploitation still loom large. Last month Macron flew to the funeral of Idriss Déby, the authoritarian veteran ruler of Chad and a key French ally for decades, to make clear to local rebels that Déby’s son and unelected successor was France’s protégé. Then there is the bloody intervention in Mali, where French troops have tried for a decade to help local forces suppress Islamist extremism without success.

In South Africa, such reminders of the priorities of a non-too-distant past were kept far away, symbolically as well as physically. Instead, Macron focused on winning hearts, minds and contracts with offers of aid, support for vaccine production in Africa and streamlined commercial ties.

“There will always be some who say it is too little, too late,” said Berville, speaking hours before his flight with the president back to Paris on Saturday. “But there is an entire generation in Africa who want to transform relations with France. In politics, you have to be responsive to reality.”