On the field Maro Itoje is a dominant presence. But in front of his old headmaster, after Saracens played Ampthill at home, the England and Lions lock is polite and deferential, showing respect that counts double as that same man set him on his path to rugby greatness.

“Hello Mr Steadman,” Itoje says with a nervous smile. Floyd Steadman first spotted the 26-year-old’s rugby potential during his time as headmaster at Salcombe prep school in the London suburb of Southgate.

“I paid little attention to rugby until Mr Steadman suggested I play, but I followed his advice. I began playing when I attended St George’s School and then went with a classmate to Harpenden Rugby Club,” says Itoje, who is now involved with education himself as a patron for The Black Curriculum, an initiative which aims to address the lack of black British history in UK schools.

“Mr Steadman rarely mentioned that he had played for Saracens at such a high level,” he adds. “But his love of rugby and Saracens always came through when he spoke about me playing and it is good to see him when he comes and watches us play.”

Steadman says: “Maro was big, he was a sportsman. He was a tall boy and always loved his basketball and he was very, very athletic. The conversation I had with him one day was: ‘You would be a really good rugby player, you’re ideal for rugby.’ He was a bit reluctant, but I said: ‘I’ll speak to your Dad about it’ and I did. I said: ‘You’ve got to get him playing rugby and you’ve got to take him to Saracens.’”

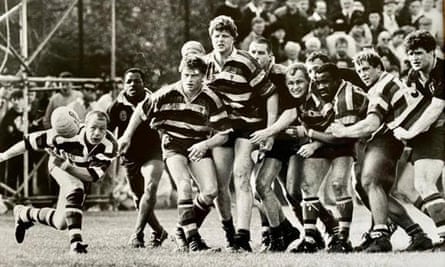

Itoje was a foot taller than his schoolmates and thrived at many sports as a junior. But Steadman had more reason than most to recognise Itoje’s potential and back his own judgment. In the amateur era Steadman played for Saracens 469 times over 10 years from 1980, and in 1989 captained them to promotion to the old first division for the first time with 11 wins from 11. He was a pioneer in the English club game as captain and scrum-half, at a time when black players tended to be either the big man in the pack, or the flyer on the wing.

“It was incredibly brave of them [the Saracens board] because there was no other black captain,” Steadman says. “I got a lot of interest in the national press [earlier] and thought it was because I was 23 or 24, but I found out that the interest was because of the colour of my skin, playing scrum-half, and being captain.”

Steadman’s background was far from the stereotype of rugby union as an upper middle class sport. The son of Jamaican immigrants and born in north-west London, Steadman says his father’s violence forced his mother to leave and he never saw her again after his third birthday. From the age of nine he lived in care. “I was in a really loving environment, but it’s not home.” At Kingsbury High School in north-west London his PE teacher Brian Jones, a Welshman, pushed him towards rugby. Jones also came to Steadman’s aid with a room to rent when he was 17 and social services wanted him to leave care despite him being halfway through his A-levels. It was a sliding doors moment. Steadman completed his A-levels, earned a place at Borough Road College (now part of Brunel University), and left with a teaching degree and a request from Saracens to begin training with them.

“The 70s were very tough,” Steadman admits. “When I do my presentations, I talk about the language that was used that is unacceptable now. This was the time of Love Thy Neighbour and me and the other black boys got involved in so many fights because of the names we were called because of what was said at the time that many thought was acceptable.

“Rugby gave me the chance to shine and through that people looked at me a different way, they treated me differently and treated me with more respect. Rugby opened doors,” Steadman reflects. “Rugby was different because when you play rugby it is team work, and everyone knows you are playing together. You put your body on the line and your teammate is there to protect you and vice versa. You are all in it together.”

During his Saracens career and appearance for Middlesex and the Barbarians he encountered racist abuse. On one occasion the then-Saracens captain Alex Keay threatened to take his team off if the referee Roger Quittenton didn’t do something to stop the abuse that Steadman and his black teammates were receiving. Playing for Middlesex, Steadman was racially abused by one of his own teammates. Crowds greeted Steadman and other black teammates with monkey chants and being stopped by police on his way home from training was a regular occurrence.

“Things you had to put up with, and you did, you did for the sake of the team,” he says. “When you start saying don’t call me that you lose the balance, the trust of the team. So sometimes for the greater good of the team you had to put up and shut up.

“They did it to put me off my game. I had ways of retaliating, so if we were winning I would say: ‘Look at the scoreboard’ and they’d hate that. Some of the big guys would thump me and I loved that. I loved the physical element of rugby and they would thump me, and I’d smile and say: ‘Is that the best you’ve got?’ and they hated that. You learn psychologically to be really, really tough because in that era it was acceptable to dish it out.

“I always felt, rightly or wrongly, that people were waiting for me to make a mistake and then it would be a case of: ‘Well, you know why, don’t you. He’s just not good enough, we’ve always told you that’.”

Saracens continued to improve under Steadman’s leadership and the team that went up in 1989 featured a young Jason Leonard. The next season, Steadman’s last for Saracens, they nearly won the first division but lost to Wasps on the final day.

Away from rugby Steadman forged a groundbreaking path in teaching despite being interviewed by school governors who were generally “white, middle-class, pompous, conservative men”. He went on to become headmaster of four private prep schools.“When you’re a young teacher and young rugby player there is always discrimination out there and you learn to live with it, as painful as that is,” Steadman says. “It is not water off a duck’s back, it is still very painful, but you learn to live with it and disguise the pain and get on and do your job.

“Something you’ll hear a lot of minority people say is you had to do your job twice as well as others. If I were going for an interview, I couldn’t just be OK, I had to stand out. If I didn’t stand out I wouldn’t have stood a chance. It is actually the same on the rugby field. I couldn’t just be OK – I had to be better.”

Steadman works with the Drive Forward Foundation, a charity that provides education and opportunities for children and young adults who have grown up in care. With a background in rugby and education, and his current consultancy work at the age of 62 that takes him into schools to talk about unconscious bias, Steadman would appear to be a perfect candidate for the Rugby Football Union’s diversity and inclusion advisory group, although he has not yet been asked.

“I’m helping schools kickstart these conversations,” he says. “From that point of view there is no question that the RFU are behind the curve. The RFU have missed tricks on many occasions. Why have the RFU or Saracens not used me? Clubs and societies who I have played with in the past are missing out on my skillset and experiences. I’m 62 and hope that I will be around for the next five, 10 to 15 years. I hope that I have a lot to give, but at some point I will slow down and step away. Before then I want to give something back.”

Steadman praises Harlequins’ work going into non-rugby-playing schools to develop and give opportunities to children from a variety of backgrounds, and says that any London club that doesn’t feature black players is “doing something wrong”.

The one county union to have tapped into his knowledge is Berkshire under Wayne Foncette, a former teammate for Reading West Indians. It is a group whose progress he considers to be far ahead of the RFU’s. “Wayne has done a brilliant job and Berks will be so far ahead of the other counties with diversity and inclusion because of what Wayne has done and who Wayne has brought together. What we are putting together will have the RFU and other county unions coming to Wayne for advice because he has been very proactive.”

Steadman says rugby is only just starting to fully understand what diversity and inclusion means, and while he may not be included he hopes the right people are involved to help explain what is needed and what they have gone through.

“All clubs need to be more savvy when it comes to talent awareness and talent development,” he says. “We know that the competition is football, or it might be cricket, or it might be something else, so you have to give such a compelling reason that this youngster who is so talented and may be talented in so many other sports should pick rugby. If they are from a minority background they can look at people like me and I can tell my story. For a lot of youngsters, you have to see it to be it.”