- India

- International

Torn between poverty and bonded labour, these children find no solace in laws either

Officials have refused to consider them bonded labourers due to lack of “documentary evidence” or proof of debt bondage or simply due to a plain denial of the existence of the menace

A child labour's home in Bhain village of Rajasthan’s Pratapgarh district.

A child labour's home in Bhain village of Rajasthan’s Pratapgarh district.Date: 7/4/2014

I, Ghevaram, son of Ramaji Rebari, a resident of Lapod village in Sumerpur tehsil of Pali district, have decided to pay Rs 1,700 a month to Shivlal’s son. I have delivered Rs 20,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 20,500 to Shivlal’s home.

Little did the eight-year-old, know that the “contract” would condemn him to 2,552 days of exploitation: grazing a herd of 300 sheep in the wilderness of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh in unsparing summers and harsh winters, a daily walk of 20-30 km, frequent flogging if sheep strayed into standing crops, and sleep deprivation. Sundays did not cheer him up. Festivals only brought extra dollops of jaggery and slivers of mutton. At night, a tarpaulin or sometimes the sky was his roof and a threadbare mat his bed. His one-room thatched house was a distant dream. So was school.

Now, having grown into a wiry frame, the tribal child returned home to an indifferent father, a loving mother, five brothers and a sister for the first time in seven years on April 5. From Bhain village of Rajasthan’s Pratapgarh district, the teenager had forgotten his native Vagadi dialect and spoke in argot-pidgin Hindi.

“I had seven mouths to feed. What option did I have?,” his father Shivlal, a farmer with two and a half bighas of land, defended the “contract” with the ‘gariya’ (herder) from Pali district.

House of a child labour in Chundai village of Banswara.

House of a child labour in Chundai village of Banswara.

The Indian Express tracked down around two dozen tribal children who had worked or are still working as shepherds on an annual contract basis in two tribal districts Pratapgarh and Banswara in Rajasthan. Aged between 8 and 14, they all had the same refrain: no off days even if sick, less food and water, physical assault, restriction of movement and sub-standard living.

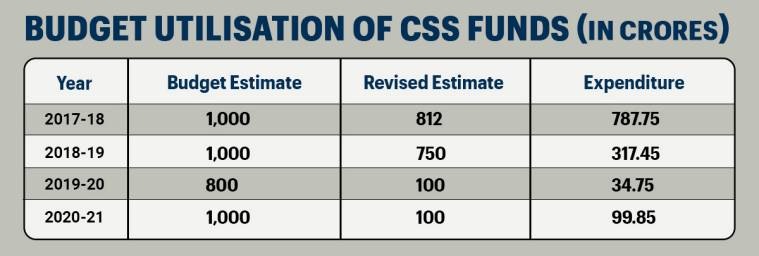

Despite their exploitation, the rescued children from the two districts have been excluded from the Union government’s Central Sector Scheme (CSS) for freed bonded labourers. This, activists argue, has violated the Supreme Court’s judgments describing all kinds of forced labour as bonded labour.

Officials have refused to consider them bonded labourers due to lack of “documentary evidence” or proof of debt bondage or simply due to a plain denial of the existence of the problem.

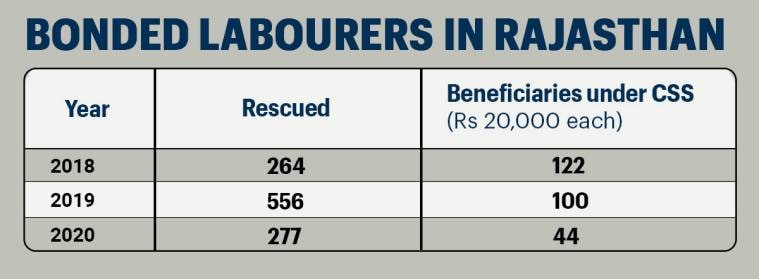

Under CSS, a victim can receive Rs 1,20,000 to Rs 3,20,000, besides other benefits. Even if these children were considered bonded labourers, their chance of getting full compensation under CSS would be next to nil because data from Rajasthan paints a sombre picture. Of the total 1,097 bonded labourers rescued in 2018-20, none had been fully compensated. Only 266 were handed over the minimum immediate relief of Rs 20,000 each.

The full compensation is given after conviction under a summary trial to be completed within three months by a district magistrate. In 2018 and 2019, the state had registered just eight cases involving an equal number of victims under the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 (BLSA).

Another kids home in Kuwaniya (Banswara)

Another kids home in Kuwaniya (Banswara)

In India, 11,849 bonded labourers had been set free, and Rs 13.13 crore disbursed under CSS, according to then Labour Minister Santosh Gangwar’s statement in the Lok Sabha on March 22, 2021. This translates into an average payout of Rs 11,081 to each bonded labourer — Rs 8,919 less than the minimum relief. The Centre does not maintain data on fully compensated victims.

Among the first bonded labourers to have been fully compensated was one Rihana Begum of Bihar who fought a two-year legal battle with the help of NGO Bandhua Mukti Morcha in the Delhi High Court (Nirmal Gorana vs NCT of Delhi). “How many Rihana Begums can approach the court for full rehabilitation? Based on our experience, we believe that fewer than 1 per cent of the freed bonded labourers with ‘Release Certificate’ can get the full amount. The reasons include lack of awareness among officials about BLSA, official apathy, migrant nature of workers and power imbalance between the labourer and employer,” said Nirmal Gorana, general secretary of Bandhua Mukti Morcha.

*********

The divide over definition

Section 2(g) of the BLSA defines bonded labour as: “the system of forced, or partly forced, labour under which a debtor enters, or has, or is presumed to have, entered, into an agreement with the creditor…” However, officials use it as a fig leaf to deny benefits to victims. “Unless it is proved that children were working to pay off debt, they won’t qualify for CSS,” stressed a senior official from the state Labour Department.

The Supreme Court, in its various judgments over the years, has chipped away at the narrow reading of bonded labour. In its landmark judgment in 1983 (Union of India Vs Bandhua Mukti Morcha), the apex court declared, “…Whenever it is shown that a labourer is made to provide forced labour, the Court would raise a presumption that he is required to do so in consideration of an advance or other economic consideration received by him and he is therefore a bonded labourer.”

Sampurna Behura, director (legal) of Bachpan Bachao Andolan, contended that the definition of bonded labour could not be held ransom to the proof of debt bondage. “These children work beyond reasonable hours, walk 20-30 km daily, lack minimum standard of living, get regularly beaten up and are paid less than the minimum wages. They deserve to gain from CSS,” she said.

A home in Miyasa village.

A home in Miyasa village.

Pratapgarh Child Welfare Committee (CWC) chairperson Jagdish Chandra Purohit said the children were not bonded labourers “because they are grazing sheep with their parents”. But none of the children interviewed were related to the shepherds.

Banswara CWC chairperson Dileep Rokriya refused to comment, saying he was only a month into the job and was not aware of the bonded labour laws. Banswara SP Kavendra Singh Sagar said: “As far as I know, no case under the BLSA Act has been registered in the district.” In the last three years, the two districts had not registered even a single police case under the BLSA.

****

‘Toothless’ child labour law

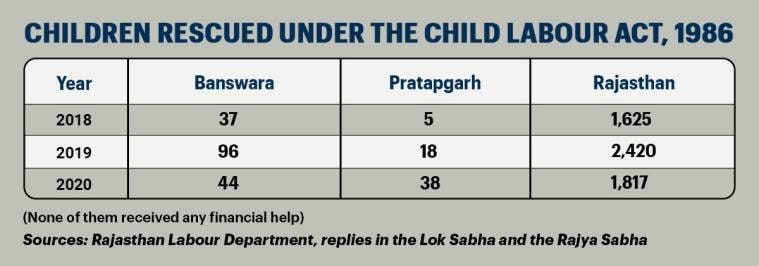

Due to official apathy, the minors are simply considered child labourers under the Child and Adolescent Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, or CALPRA. Under CALPRA, termed “toothless” by activists for lower compensation and protracted legal battles, authorities have to deposit Rs 35,000, including a maximum penalty of Rs 20,000 imposed on an employer, into the rescued child’s bank account. However, the aid remains only on paper in the state.

Between 2018 and 2020, Rajasthan freed 5,862 child labourers, including 238 children, from the two tribal districts but none of them have received financial aid. “We have reunited them with families and sent them to schools though,” said Hemant Patidar, director of the Banswara Social Justice Department.

Former Pratapgarh District Magistrate Renu Jaipal argued that the children could not be compensated in the absence of “documentary evidence”. “However, we have ensured that all these children are in school, and their parents have been restrained from resending them to work. At the panchayat level, we have made villagers take oath against child labour. Since 2019, no herder case has come to our knowledge,” she said. The Indian Express found that only three of the interviewed children were in school while the rest were either lugging bricks at construction sites or hunting for odd jobs.

Police claimed children were no longer employed by herders after 2019. “Such cases are no longer reported in our district after 2019 (when 11 children were reunited with their families). I challenge you to show me at least one case,” said Kailash Singh Sandhu, Banswara additional superintendent of police.

******

Jurisdictional jeopardy

When a child is freed from bonded labour, the rescuing state informs the source state and coordinates with district authorities, including CWCs, for compensation and rehabilitation. The rescuing state is required to issue a ‘Release Certificate’ or Bandhua Mukti Praman Patra (a preliminary proof of bondage) to the victim and grant an immediate relief of Rs 20,000.

Indifferent district authorities are averse to pursuing such cases on the pretext of jurisdictional constraints. For example, three children from Pali were freed from a shepherd and issued ‘Release Certificates’ by Khargone district in Madhya Pradesh. The immediate relief of Rs 20,000 was denied to them by Khargone. “We did not have their bank details. Moreover, they were from Rajasthan. So, Rs 20,000 should be disbursed by the source state,” said Rahul Muvel, Khargone labour inspector. Pali CWC chairman Sitaram Sharma said the three children could not benefit under CSS because “they said they had gone to MP to meet their parents”.

A senior official from the office of the Director General of Labour Welfare explained that interim relief can be disbursed by the rescuing state and the final compensation by the source state.

Activist Behura said, “A child may not understand the meaning of exploitation and share his/her experience from the word go. To ensure this, the CWC has to hold several counselling sessions before they are comfortable to share details.”

Similarly, several bonded labourers rescued from Rajasthan were denied even the interim relief because they were migrants. At least six of the freed bonded labourers from Rajasthan could not get Rs 20,000 as they were wrongly categorised as “migrant workers”, the state Labour Department’s records revealed.

****

Targeting tribals

Every year, the pastoral Gariya community from Pali, Jalore and Sirohi districts leaves with its families and livestock for Madhya Pradesh in summer. Along the route, herders are always on the lookout to hire children, preferably below 10. During their stopover in Banswara and Pratapgarh, they contact middlemen to rope in impoverished tribal children.

“The reasons for employing tribal children are manifold: they can endure physical exploitation on less food, demand less wages (from Rs 1,500 to Rs 4,000 a month) and are pliant. Once they reach adolescence, they are returned to their families due to the herders’ perceived insecurity towards their women and daughters. Lack of schooling then reduces these young adolescents to unskilled labourers,” explained Kamlesh Bunkar, a member of Banswara Childline. Villagers revealed that children with single parents, alcoholic fathers and those born due to lack of family planning are also forced into labour.

In Chundai village of Banswara, the uncle of a 13-year-old who fled from regular beatings by his herder in MP’s Ratlam district in 2019 said herders had woken up to the importance of education. “While their children go to school or colleges, poor families are being targeted,” he said. A small colony of 22 households in Chundai has been sending their children to graze sheep.

In another village in Banswara, a 14-year-old child, who was surreptitiously brought back from Madhya Pradesh after six years, recalled how he was allowed to bathe only once a fortnight and could not sleep on the bare ground for the first few days. “During rain, our tarpaulin cover used as a blanket would leak,” said another from Bhain village.

Though there is no official estimate on the number of children working as shepherds, Pratapgarh MLA Ramlal Meena claimed that nearly 60 per cent of the district panchayats were reeling under this modern form of slavery. “The district administration needs to survey the vulnerable villages from where children migrate,” he said.

Local activists said villages untouched by the bountiful flow of the Mahi river are more vulnerable to poaching by herders. Banswara Childline has been involved in bringing back two dozen children from herders in the last two years.

In Madhya Pradesh, Ratlam Juvenile Justice Board member Jeevraj Purohit, whose term as CWC member ended in January 2021, said 948 children including around 100 who grazed sheep were rescued in Ratlam district, which borders Rajasthan, in the last three years but no ‘Release Certificate’ was given.

*******

The Way Forward

Two officials from the Rajasthan State Commission for Protection of Child Rights (RSCPCR) and the Directorate for Child Rights (DCR) said if officials are sensitised about CSS and BLSA, a turnaround is possible. They agreed that the extent of exploitation of the interviewed children makes them eligible for the rehabilitation scheme. “CWC members and district officials are ignorant as to how CSS can support bonded child labourers,” said the RSCPCR official. “If I had known about CSS earlier I would have insisted on getting the ‘Release Certificate’ from the district administration for these kids,” said a former Banswara CWC member who completed his term in May.

The Indian Express interviewed around two dozen children, who had grazed or were grazing 200 to 400 sheep each. They hail from eight tribal villages in the hinterland of Pratapgarh and Banswara districts in Rajasthan. All of their households are involved in farming and own small landholdings.

Children’s age: 15 and 14

Years of work: 5 and 6

Village: Kuwaniya (Banswara)

His father surreptitiously brought him back after Childline learnt about his disappearance. The mentally unstable child, who was handed over to a herder for Rs 2,000 a month, now wants to resume school. “Who would admit him in school? He is too old,” said his father who owns a one-bigha plot.

Another 14-year-old child returned home after six years in April. “I hated waking up at 4 am to milk 400 sheep… I was allowed to take a bath only once a fortnight,” he said.

Child’s age: 14

Years of work: 2

Village: Bhain (Pratapgarh)

Unable to tolerate constant beating, the child fled Indore in 2019. “I was given a 500 ml water bottle for the whole day. That was not enough and sometimes I thought I would die of thirst,” he chuckled. He is now looking for odd jobs. Every household in the village has, over the years, sent at least one child with herders.

Age: 12

Years of work: 2

Village: Khalakhet (Banswara)

The child is still herding 200 sheep in the wilderness of Madhya Pradesh. When asked if the family had recently spoken to him, his elder brother declared: “The gariya won’t allow any phone call. My brother has gone to work not to talk.”

Age: 13, 11

Years of work: 1

Village: Miyasa (Banswara)

The two brothers dropped out of school because they “wasted their time in playing games”, their father, a farmer, said. Their mother had left the family after giving birth to the younger brother. The brothers are herding sheep in a neighbouring village, 60 km away, and earn Rs 4,000 a month.

Age: 13

Years of work: 2 years

Village: Chundai (Banswara)

The child called it quits in 2019 after he was caned for his inability to discipline sheep. He was found in Ratlam and brought back to Banswara. He is studying in Class 3. Five other children from the village also recounted that beating was the price they had to pay for survival. At least 22 households have, over the years, sent their children with herders.

Age: 12 & 6

Years of work: 1

Village: Kataron ka Kheda (Pratapgarh)

The brothers were rescued in 2019 with the help of a school teacher. When they returned, the two had blisters on their feet and were emaciated. “A lot of people came after the rescue. Officials promised help, but we are still waiting,” their grandmother complained. The children’s mother allegedly eloped with another man six years ago. While a younger brother is studying in Class 4 and can rattle off poems, another brother works as a construction labourer with his father.

Age: 10

Years of work: 1 month

Village: Patinagra (Banswara)

The child was asked to return home in March as he could not keep pace with the herd due to festering wounds on his legs. Asked if he wanted to return to school: “How can I go to school when my father insists that I work for the gariya. If I protest, he beats me up.” He dreams to become a “sarkari naukar”.

Age: 14

Years of work: 3 months

Village: Saumpur (Banswara)

In 2017, the orphaned child was sold to a herder by his eldest brother for Rs 1,500 a month. Unable to bear the physical abuse, he fled and was found in Madhya Pradesh’s Nagda district. “I dream to become a police officer and catch terrorists,” said the child, now a Class 5 student.

Rehabilitation of bonded labourers

*Upon rescue, the district administration is required to issue a ‘Release Certificate’ and immediately deposit Rs 20,000 into the bonded labourer’s account as an interim relief under the Central Sector Scheme (CSS), 2016

*The district magistrate/sub-divisional magistrate holds a summary trial, which has to be completed within three months

*The rest of the rehabilitation amount (Rs 1 lakh to 3 lakh) is to be released after conviction of the accused in the summary trial or regular trial under judicial process

*The final amount is Rs 1 lakh for adults, Rs 2 lakh for children and women and Rs 3 lakh for orphans, widows, differently abled people and transgenders. The scheme is fully funded by the Central government

*Besides, the state government can also fund housing plots, land for farming, employment, health and education

India

11,849: Bonded labourers rescued/rehabilitated since the Central Sector Scheme (CSS) was launched in 2016

Rs 13.13 crore: Amount disbursed in the same period

Rs 11,081: Average payout per freed worker

*Union Labour Ministry does not maintain data on fully-compensated victims

Apr 16: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05