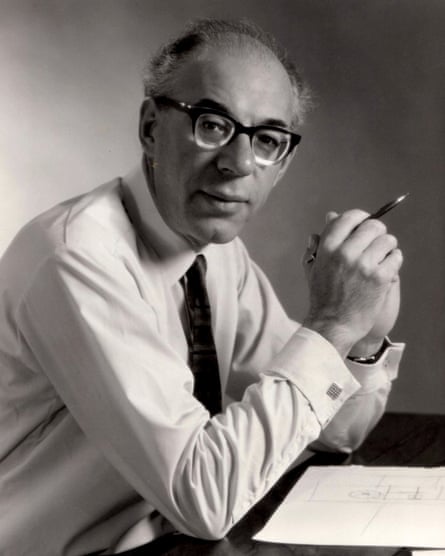

John Stillman, who has died aged 101, was the architect responsible for designing dozens of new schools across Britain in the mid-20th century, when the postwar baby boom created an urgent need.

The name Stillman had already been associated with school architecture, since his father, Cecil, as county architect for West Sussex and then Middlesex, had turned to the caravan industry to prefabricate classrooms when faced with a rapidly rising population. He inspired his son to go into the same profession, and commissioned two of his first buildings, schools in Chiswick and Harrow, completed in 1954.

John Stillman went on to design schools throughout the UK and in Gibraltar, in partnership with John and Elizabeth Eastwick-Field. Their stripped-down, modernist designs articulated the era’s concern for natural light and healthy living, exemplifying the belief that functional buildings, produced scientifically, would stimulate young minds, especially in small towns and rural areas where there were few secondary schools before 1945.

These large schools on the edges of small towns transformed education in Britain. They were so universal as to be taken for granted, and many have been rebuilt since 2000.

Stillman’s work exuded calmness and efficiency as well as good looks. Stylistically he moved from an understated minimalism in early works such as the Camden school for girls (1956-57) to a richer texture of concrete and brick in the 1960s, first at Hampstead school (1966) and then at Clissold school, now Stoke Newington school (1970), all in London. He built large numbers of schools in Cheshire and in Devon, notably at Ilfracombe, Bideford Newton Abbot and Totnes. He was particularly proud of additions to the historic Plympton grammar school, and he also extended Ridgeway school in the same town.

Whereas his father had pioneered quick-fix prefabricated solutions, John was fascinated by the materials, detailing and process of architecture. This was apparent as early as 1951 when he described the construction of the Royal Festival Hall in a pioneering series of technical articles for the sector’s leading trade magazine, Architects’ Journal, ranging from its drainage (the land was partly reclaimed from the river) and methods of construction to the planning, finishes and the acoustics of the actual concert hall.

When he created the 23-storey Hide Tower (1961), built not far from Westminster Cathedral, its small but well-equipped flats offered a high standard of accommodation mainly for older people, with a laundry and rooftop club room. It was an early example of the use of pre-cast panels for such a tall block, assembled quickly by one of the first tower cranes brought from France. Stillman’s research found that people without children liked living high up. The building won a Ministry of Housing medal in 1962.

Above all Stillman was interested in joinery, from the choice of fine hardwood finishes then available from the Commonwealth to the use of rough timber formwork to support large structures into which concrete was poured and allowed to harden. This led in 1954 to the award of the Alfred Bossom research fellowship, jointly with John Eastwick-Field, and resulted in their book, The Design and Practice of Joinery, first published in 1958, which went through four editions.

Having begun with schools, like many of his contemporaries Stillman went on to work extensively across the public sector. Hide Tower was followed by a second block of small flats for Westminster city council, William Blake House in Soho (1964-67), and meanwhile the practice designed several estates for London county council, such as Lister House, a nine-storey block built in 1956 on land in Whitechapel vacated by the London hospital and noted for its combination of efficient planning and a streamlined appearance.

More prestigious schemes followed at the new universities being built or expanded as the baby boom generation reached adulthood. At Keele University, Stillman and Eastwick-Field’s students’ union, opened in 1963, was a large building with shops, meeting rooms, a bar and a double-height ballroom.

Most impressive was a complex of buildings for teaching science and engineering at Brunel University (1968), then under construction as Britain’s first purpose-built college of advanced technology. The limited budget had to be spent on services for a group of laboratories and workshops that was one of the largest of its kind in Europe, four towers linked by lower blocks that form a series of connected courtyards, their shuttered concrete relieved by large areas of patent glazing.

John was born in Middlesex, the son of Cecil and his wife, Alma (nee Webb). After attending Peter Symonds school in Winchester, he entered the Bartlett School of Architecture in London in 1937, moving with it at the outbreak of war to Cambridge. He quickly became friends with the Eastwick-Fields, and the three formed a partnership in 1949. In the interim Stillman served with the Royal Engineers in India, where in 1944 he met and married Anne Stanton, a nurse from Wentworth, Yorkshire. They had two sons.

Like other medium-sized architectural firms, the three senior partners relied on a team of loyal assistants, led by Ralph Smorczewski, and following their retirement in 1986 the practice continued as SEF Architects, run by David Stephens and Humphrey Lukyn-Williams.

In retirement Stillman devoted himself to painting and had several exhibitions in north London and with the Society of Artists in Architecture. He was appointed OBE in 1976.

Anne died in 2015. He is survived by his sons, Martin and Andrew.

John Cecil Stillman, architect, born 27 May 1920; died 19 July 2021

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion