- India

- International

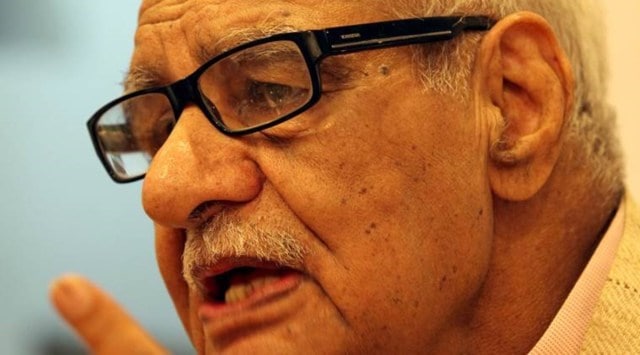

Kuldip Nayar created pathways in dark times

Remembering Kuldip Nayar on his third death anniversary.

Kuldip Nayar was among the journalists who had staunchly opposed the Emergency and was jailed during that period. (Express Photo by Ravi Kanojia)

Kuldip Nayar was among the journalists who had staunchly opposed the Emergency and was jailed during that period. (Express Photo by Ravi Kanojia)Written by Meera Diwan

Jab kashtī sābit-o-sālim thī sāhil kī tamannā kis ko thī

Ab aisī shikasta kashtī par sāhil kī tamannā kaun kare

(When the boat was steady and secure

Who would have liked to meet the shore?

Now that the boat is sinking

Who can hope to meet the shore?)

-Moin Ahsan Jazbi

For the past three years, the Wagah-Attari border has fallen silent and desolate, come August 14. Thirty years of celebrations under the night sky, with the satisfaction of shared bonhomie, are now relegated to memory. Citizens on both sides of the Indo-Pak border had gathered and greeted each other by candlelight. The soloist was Kuldip Nayar, chanting “Hindu-Muslim, Bhai Bhai”, to a chorus of “Bhai Bhai.” Poets, politicians, seculars, sceptics were volunteers of his peace-keeping force.

There was much to celebrate during those heady midnight vigils — three birthdays; one each of the two nations meeting like estranged siblings, much as midnight meets daylight, setting aside ill feelings; the third, the day of birth, appropriately, of their go-between and willing matchmaker, Kuldip Nayar. Boundaries did blur, lightening dark memories into softer focus.

An atheist who believed in destiny, his weaving of words could well convince his readers that his departure date, August 23, 2018, was predetermined. Forward-looking and generous, this down-to-earth dreamer did not leave his following of readers completely bereft. Within the legacy of his printed pages are directions and instructions, some expressed in explicit prose, some to the rhythm of quoted verses; others as evidence through lived experiences. A treasure hunt with clues and hints revealed within them guide us through unlit paths, out of the dark nights that history recycles from time to time.

An atheist who believed in destiny, his weaving of words could well convince his readers that his departure date, August 23, 2018, was predetermined. Forward-looking and generous, this down-to-earth dreamer did not leave his following of readers completely bereft. Within the legacy of his printed pages are directions and instructions, some expressed in explicit prose, some to the rhythm of quoted verses; others as evidence through lived experiences. A treasure hunt with clues and hints revealed within them guide us through unlit paths, out of the dark nights that history recycles from time to time.

On August 14th 1947, Nayar had watched the communal fires from a distance, in his native Sialkot. “My mother tip-toed to me and whispered in my ear: These are just lights. Today is August 14th, your birthday.” Gathering courage, the 22-year-old left for Amritsar, with Rs 200. Families crossing borders individually or in smaller groups was a survival strategy.

Reaching Delhi, at Urdu Bazaar, now Chandni Chowk, he would meet his mureed — not a chance encounter as he would have us believe. Syed Fazl-ul-Hasan had adopted the pen name of Mohani, after the town of his birth, Mohan, in Unnao district of then-United Provinces. Hasrat Mohani was a freedom fighter who coined the slogan “Inquilab Zindabad”, a communist who described himself as an ishtaraaki or socialist Muslim. A renowned Urdu poet, he felt no contradiction in composing verses in praise of Lord Krishna and occasionally participating in Janmashtami celebrations at Mathura, well within reach from his hometown.

The young murshid, Kuldip Nayar, would surely find this multi-faceted personality admirable, if not irresistible. He could relate to Mohani’s belief in a gradual transition from capitalism to socialism by democratic means — ishtaraakiyat or communal living. As a teenager in Sialkot, he had a tattoo of a crescent moon and star embossed on his forearm, an expression of fellowship and in farewell to his close friend, Bashir. Perhaps this was his personal genesis of the annual border chant “Hindu-Muslim Bhai Bhai”.

The young murshid, Kuldip Nayar, would surely find this multi-faceted personality admirable, if not irresistible. He could relate to Mohani’s belief in a gradual transition from capitalism to socialism by democratic means — ishtaraakiyat or communal living. As a teenager in Sialkot, he had a tattoo of a crescent moon and star embossed on his forearm, an expression of fellowship and in farewell to his close friend, Bashir. Perhaps this was his personal genesis of the annual border chant “Hindu-Muslim Bhai Bhai”.

When the family left Sialkot, he wrote: “I did not want to leave. This was my home. Our spiritual guardian was here… Not a superstition, but our faith that the grave in our back-garden was that of a peer who protected us. How could we leave the peer? The grave was our refuge, our temple.”

Under the protective umbrella of his Guru, and his self-belief that “optimism is a moral duty”, he went on to become a journalist committed to the truth of the oppressed. During a communal riot at the Kishanganj slums in Delhi, he, an editor of a leading newspaper, moved into the home of an office worker living there, for first-hand reportage of residents and local police. Journalism included humanism and a duty towards people without privilege.

Writing also meant fearlessness. Days before his arrest during the Emergency and perhaps as a consequence of continuing to speak up despite ordinances of censorship, while editor of The Indian Express, he wrote to the then-PM Indira Gandhi:

“Madam, it is always difficult for a newspaperman to decide when he should reveal what is what (the truth). Free society is founded on free information. If the press were to publish only government handouts or official statements to which it is reduced today, who will pinpoint lapses, deficiencies or errors?”

“Madam, it is always difficult for a newspaperman to decide when he should reveal what is what (the truth). Free society is founded on free information. If the press were to publish only government handouts or official statements to which it is reduced today, who will pinpoint lapses, deficiencies or errors?”

The Tihar experience, he wrote, “woke me up. I began to feel for the violation of personal liberty and human rights. The young boys interned in jail for no fault of theirs shook my conscience to the core.” He would encourage aspiring journalists to highlight the arrest of under trials, students and minorities, draw parallels between Tihar jail and Twitter jail; define conversations between enriching and impoverishing memories; keep alive the conversation of the ethics of news ownership.

In his typical self-questioning style that is both philosophical and refreshingly childlike in innocence, he wondered if he had “over-lived”. Dissatisfied with this self-assessment, I searched in vain for an appropriate interpretation. I did locate it, plagiarising his own quote from Ghalib:

“Shama har rang mein jalti hai,

Sehar hone tak.”

“The flame flickers in every hue,

Till the dawn of the day.”

“It is beyond my capacity to describe what has goaded me on and on, for over eight decades: destiny or determination?”

The answer may perhaps lie in the conviction expressed within the title of his sole work of fiction, written in Punjabi: Mainu Hanera Kuan Nahi Lagda? translated by Navyug Publishers as “ Why don’t I fear the darkness?” The backdrop of this novel stretches from Operation Bluestar and climaxes with the riots of 2002 in Gujarat. “Through this book, I have tried to express how politics and religion push people into a fire in which truth, principle and neutrality are burnt.”

Did you turn off the lights when you left? Even so, we still have the torchlight within the words, between the lines and beyond the lines. Could we ask for clearer directions, out of these dark times?

Meera Dewan is a filmmaker who produced a biopic with Kuldip Nayar

40 Years Ago

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05