- India

- International

Tea, talk, tally and temple

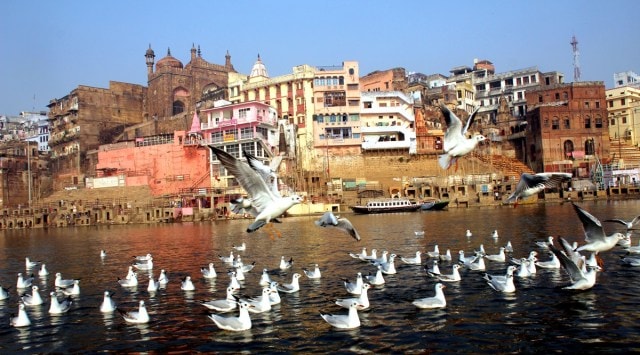

Below the Ganga waters, there are undercurrents, a desire for ‘naya chehra’, discontent over prices, bitterness over Covid, disquiet over religious rift. However, will it matter in 2022? One can’t say with Banaras.

At the ghats, Ganga’s waters have risen past the steep steps to lap at the doors of homes and hotels. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

At the ghats, Ganga’s waters have risen past the steep steps to lap at the doors of homes and hotels. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)Something was different about ‘Pappu ki Dukan’.

There is still no banner or board announcing it in the chowk. It’s still just there, a short walk through twisty lanes from Assi Ghat, where, as they do every monsoon, the Ganga’s waters have risen past the steep ghat steps to lap at the doors of homes and hotels.

Banaras is a city that savours the rituals of argument and banter nearly as much as it relishes its vivid varieties of street food. For the everyday debate, Pappu’s tea shop, small and ill-lit, a couple of smudged tables and benches against world-weary walls, is a daily nook.

Here, you don’t wait for the noise to fade or the crowd to clear before arguing. Perhaps because this knowing city and its cramped tea shop have a heads-up — they know that the mess and the noise, the beauty and the squalor, are part of the to-and-fro, not outside of it. And that you can’t cordon off the debater or the debate.

At Pappu’s tea shop, during elections and in between them, you will always find a political conversation you can join or poke, no matter what your own politics may be. On a given day, you could spar with a poet or a retired bureaucrat, a professor who has ambled in from the Banaras Hindu University campus next door, a politician in search of an audience, a daily wage-earner on a break. The discussion, no matter how heated it gets, could end with your sparring partner buying you the tea. It could leave you with a brief flash of insight, an unexpected frisson of understanding.

For the everyday debate, Pappu’s tea shop, small and ill-lit, a couple of smudged tables and benches against world-weary walls, is a daily nook. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

For the everyday debate, Pappu’s tea shop, small and ill-lit, a couple of smudged tables and benches against world-weary walls, is a daily nook. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

During a visit in February 2020, after a particularly sharp and angry exchange on the anti-CAA protests that raged at the time, just before the coronavirus forced the protesters indoors, it suddenly seemed to be writ on the tea shop wall: It’s intent, not law. The amended citizenship law, which excludes Muslims from the list of groups to be given fast-tracked citizenship, and the proposed National Register of Citizens that threatens to make the citizen’s sense of home hostage to documents and cut-off dates, are the distillation of a political message. There is no point in quarrelling about legal clauses or details.

As we sit again at Pappu’s on a sweaty August afternoon, waiting for the chai, purposeful looking men, tilaks on foreheads, come in and gesture in a peremptory sort of way. Space must be cleared on the benches for a prominent BJP leader and his entourage. The leader makes an entry and his band of supporters fill up the tiny shop barely long enough for a cup of tea over talk about the party’s “chunavi tayyari (election preparedness)”, and take a round of selfies.

But a moment has been marked that goes against the tea leaves in Pappu’s chai shop. In this Banaras corner, debate was the great equaliser, power an idea to be played with, punched holes into. It was not to be deferred to. Or ceded the tea-shop bench. Not anymore, it seems.

***

Ajay Kumar Gautam, 32 years old, and Manish Kumar Pandey, 24, two young men who drive taxis in the city, live in villages nearby. Ajay and Manish are as different from each other as a Dalit can be from a Brahmin in caste-ridden Uttar Pradesh. But the pandemic has pounded and flattened their stories, bringing the same underlying precarity to the surface.

At Pappu’s tea shop, during elections and in between them, you will always find a political conversation you can join or poke. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

At Pappu’s tea shop, during elections and in between them, you will always find a political conversation you can join or poke. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

Ajay, a Dalit, returned to work in the first week of this month, after the pandemic-induced lay-off of over a year, starting from the first lockdown in March 2020. In this period, he went back to his village Sadalpura in district Chandauli, worked on his small patch of land, and did construction jobs for daily wages. Before the pandemic, he had worked as a driver since 2018 in a Banaras hotel, which laid him off after guests dried up due to Covid. Earlier, he worked for one-and-a-half years in a Maruti factory in Gurgaon, but was forced to return in 2013, along with other young men from the district, after they ran foul of the factory’s management. They had mounted a “dharna pradarshan (agitation)” to demand adequate compensation and a job for the family of a fellow worker, who lost his arm while working. “This could have happened to any of us”, says Ajay.

Ajay commutes from his village to Banaras every day and rising fuel prices have meant that Rs 120 worth of petrol in his bike is barely enough to make the daily trip to the city and back. He got a TV as dowry when he got married in May 2017, but hardly gets time to watch it, “not even Modiji’s speeches”, because he reaches back home late in the night, and must leave for the city again early next morning at 6.30-7.

Ajay belongs to the same sub-caste as Mayawati, but his family has been voting BJP, because “the BSP government favours only a few, not the poor”, and the SP brings the fear of “Yadav raj”. But next time elections come, he and his wife will break away from the family, they want change. Next time, other factors will prevail — the local (BJP) MLA is unhelpful, but the (SP) MP is benevolent, he says.

Ajay ran from one hospital to another to arrange oxygen for his mother-in-law and his sister’s mother-in-law, when both were infected by Covid. No hospital took in his mother-in-law, she died at home. For his sister’s mother-in-law, one hospital asked for Rs 1.5 lakh for oxygen, “no guarantee”, and the family spent Rs 60,000 for treatment at a second hospital, but she died too. Giving the lie to the ubiquitous government posters that promise free vaccines, Ajay has just paid Rs 100 to register for his first shot.

“My two-year-old son runs to me every evening when I get back home, asks papa kya le ke aaye (what have you brought me). How do I tell him, Rs 120 ka toh tel hi bharwa diye (Rs 120 went only in filling petrol)”.

“Koi naya chehra (a new face)” is needed again, says Manish Kumar Pandey, a Brahmin, who also commutes daily to Banaras, from village Jalhupur, 10 km away. “We were Congressi, but voted for Modi in 2014. We thought he has risen from below, sold tea, gareebon ka samjhenge, karenge (he understands poverty, will work for the poor)”.

“Sanskriti” or culture is important, says Manish, but the main issue is “bhookhmari (hunger)”. “Ghar bhi toh chalana hai (we have to run our households too)”.

Manish’s father died in 2007, casting the burden of earning on the young boy of 10, who headed to Gorakhpur the next year to wash plates at Anuradha Coffee Centre, and from there to work in a poultry farm in Kushmi Jungle outside the town.

From there, Manish went to Mumbai, worked as a coolie-cum-helper in a garment factory. He taught himself to stitch and sew, and earned much better for the next six years, saving enough money to send home — in 2015, he remembers sending up to Rs 18,000 a month. Then, notebandi (demonetisation) happened in November 2016, and the karigar (craftsmen) bore the brunt. They were not paid on time or in full. Manish had to come back to Banaras in 2017, where he picked up work as a driver. He remembers the day he bought his own car to ply as a taxi, as if it were yesterday — August 1, 2019. Then, Covid struck.

Houses have been demolished, compensation paid, and many allege even as the Commissioner refutes, several smaller temples brought down, to make way for the 24 grand new structures part of temple project. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

Houses have been demolished, compensation paid, and many allege even as the Commissioner refutes, several smaller temples brought down, to make way for the 24 grand new structures part of temple project. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

“In the three months of the first lockdown, the car stood still. Business is now picking up, but people are still not travelling freely… About 50 per cent market sahi ho gaya hai (has recovered), but diesel is Rs 90/litre. It means that if I earn Rs 2,000 in 12 hours, Rs 1,200 goes on diesel.”

“Earlier, edible oil was Rs 50 a litre, now it is Rs 200, and the gas cylinder is touching Rs 920. Kam kharcha karte hain (we have cut our expenditure),” he says.

Manish is a devout Hindu, visits the Kashi Vishwanath temple regularly, but “insaan hee nahin rahega, toh mandir kya karega

(of what use is a temple when survival becomes difficult)”.

***

If a city has a voice different from the sum of its parts, you can’t be sure if Banaras would agree fully with Manish — so mindful does it seem to the rhythms of devotion, so readily does it give devotees the right of way.

The temple complex is a hive of buzzing activity, massive machines noisily at work, heaving, lifting and pumping. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

The temple complex is a hive of buzzing activity, massive machines noisily at work, heaving, lifting and pumping. (Express Photo by Anand Singh)

At the congested Godowlia chauraha, spread across the facade of a building that offers multi-level parking, a giant TV screen is a splash of moving light and colour above the busy crowds — in July-August, the month in the Hindu calendar dedicated to Lord Shiva, it shows rituals inside the garbha griha or sanctum sanctorum of the Kashi Vishwanath temple, live. Even the Covid lockdown days were shifted in Banaras to accommodate the pilgrim rush on “Sawan ka Somwar”, the Mondays of July-August, when devotees flock to the temple to seek “Baba’s” blessings.

There is the grand temple to Lord Ram that is being built across the state in Ayodhya. More importantly for Banaras residents, “Baba ka vistarikaran”, the large-scale expansion and renovation of the Kashi Vishwanath temple under the temple corridor project, whose foundation stone was laid by PM Modi in March 2019, is racing towards completion.

The inauguration of the renovated temple will keep its deadline of November 30 this year, says head of the Mandir Nyas Executive Committee, Divisional Commissioner Deepak Aggarwal. Houses have been demolished, compensation paid, and many allege even as the Commissioner refutes, several smaller temples brought down, to make way for the 24 grand new structures being built in eight kinds of stone. All the better for pilgrims, who come mostly from the country’s south, to make their way to the temple, and to connect the temple to the Ganga.

On a wet Sunday, the temple complex is a hive of buzzing activity, massive machines noisily at work, heaving, lifting, pumping, as pilgrims make their way, seemingly undeterred by Covid or the slashing rain. The Yatri Suvidha Kendras (pilgrimage facilitation centres), guest houses, viewing gallery, museum, hospice, food court, souvenir and book shop, ramps, lifts and escalators — they are there in skeletal forms, in different stages of completion.

Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath visits Varanasi and the Kashi-Vishwanath temple about twice in a month, people here say, and his visits continue amid Covid. PM Modi came here roughly once in three months, before the pandemic.

A message has travelled from West Bengal to politically aware Uttar Pradesh, and it pierces the inevitability of Modi. Vis-a-vis the Yogi government, too, there are mounting signs of disbelief, even within the saffron camp — from complaints about the temple renovation project to the wider Covid suffering and economic distress, from grumbling about political favours to the Yuva Vahini and Thakurs to resentment against “taana shahi” and/or “bhasha shaili” (authoritarianism, abrasive politics). But come elections, the economic distress that seems so pulsating and concerns that seem so irrefutable now, may well be overlaid. Will they be rubble under the temple, is the question.

***

The Kashi Vishwanath temple complex is adjacent to the compound of the Gyanvapi mosque — this mandir-masjid dispute is still unresolved, still in court. The entry from the road is common to the temple and mosque. “If we build for the temple, mosque goers will benefit too,” says Commissioner Aggarwal.

Yet in the run-up to another election, old anxieties are being stoked again.

“They will play the Hindu-Muslim card when the election comes,” says a Muslim sari-seller in an upscale locality, who doesn’t want to be named. He refers to the line that divides his Muslim dominated mohalla from the Hindu neighbourhood next-door as the “border”, in a normalised, matter-of-fact way.

So what has changed after the BJP swept to power in 2017? “Earlier, every few days, two or three times in a month, I would go with my family to the banks of the Ganga, to roam on the ghat, rent a boat, have dinner, and not worry about the evening fall. Now we try to get back home before dark. Now we hesitate to go out… ched-chaad aur badtameezi karte hain (they trouble and threaten us),” he says. “People from good families have stopped venturing out of the mohalla after dark”.

And then, many point out, the Opposition seems unresisting or absent. In Yogi raj, under Akhilesh Yadav, the Samajwadi Party has seemed more active on Twitter. Mayawati’s tightly controlled BSP does not easily come out on the streets anyway. “Leaders of the Opposition need to vigorously stand up to the Yogi government’s bid to silence political disagreement and protest, they should be prepared to even go to jail…,” a former journalist says.

***

“Banaras ke logon ka kuch theek nahin hai, seedhe chalte-chalte kab ghoom jaayen, kuch pata nahin (the people of this city can take you by surprise, you make a prediction at your own peril),” the Banaras resident will say.

Banarasi exceptionalism is real as well as imagined. Yet it would indeed be foolish to second guess this “galiyon ka sheher”, this city of narrow lanes, where traffic must weave and reverse to move forward, where lines lose their straightness, and where negotiation is a daily staple.

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05