You could measure my life in recipes. Each one a letter to a friend, a story of something I have made for dinner, the tale of how it came to be on my table. A salad tossed together with broad beans, salted ricotta and the first white tipped radishes of spring; a roast chicken, its crisp skin served with a fat jug of its roasting juices on an autumn day; or a gloriously messy platter of grilled aubergines, hummus and torn flatbread shared with the best of friends.

That letter might accurately chronicle the details of a cake with which I am quietly pleased, tell the reader of a quince that has simmered peacefully in lemon juice and orange-blossom honey on my hob on a winter’s afternoon, or mention a pillowy dumpling I have just lifted from a steaming bamboo basket. Sharing food with those at your table – passing round a bowl of late autumn raspberries or a slice of sugar-encrusted blackberry and apple pie – is heartwarming enough, but a recipe posted in a newspaper, ephemerally on social media or in more lasting form in the pages of a book has the chance to be shared even more widely. It is just a recipe, a suggestion for something you might like to make for others, but it is what I do.

The first recipe I encountered – for a Christmas cake – belonged to my mother. Handwritten on a piece of ruled Basildon Bond notepaper, it lived in the bowl of the electric mixer that only saw light of day once a year, when I helped her make The Cake. The first cooking I did on my own was a tray of jam tarts – blackcurrant, marmalade and raspberry. The ghost of them lingers still, me standing on a stool in an attempt to reach the kitchen table, rolling out scraps of pastry into a craggy rectangle with a red-handled wooden rolling pin, pressing Mum’s crinkle-edged cutters into the pale dough and filling the little tarts with jam as bright and clear as jewels. The jam boiled over and glued the tarts to the tin, but peeling off the chewy crumbs and eating them was a delight.

There is something – and this is the point really – that goes hand-in-hand with making something to eat, that transcends putting the finished dish on the table. Cooking is about making yourself something to eat and sharing food with others but is also about the quiet moments of joy to be had along the way. Watching the progress of dinner as you stir onions in a pan, at first crisp, white and pungent – you may have shed a tear – then slowly becoming translucent gold, darkening to bronze, all the time becoming softer, sweeter. Take them too far though, and the sweet onions will turn bitter. And that is where a good recipe comes in and partly the point of what I do; to guide a new cook towards a pleasing dinner and, for those who have been cooking for years, to share a recipe they may not know.

I am not a chef and never have been. It is no secret that I ran away from the heat of the professional kitchen. The stress and frenetic speed of the work, the dedication required to be really good at what you do and the relentlessness of that life simply wasn’t for me. I wanted to cook for a living but without the seasoning of stress and adrenaline. I fell into writing about food by accident – while working in a rather lovely cafe – so it is odd to think I have had a cookery column for nigh on 30 years, written 10 cookery books and penned a memoir (which itself spawned a film and stage play). My respect for professional chefs not only remains undimmed, but I find myself in awe of what they do. It just wasn’t my thing.

Potato and burrata

A contemporary version of the cheesy chip supper. Thicker wedges, baked in the oven, then eaten while almost too hot to hold, dunked into a mound of cool, milky cheese. The cheese will be split open to reveal the snowy curds within; a little puddle of olive oil, chopped tomatoes, capers and gherkins sit on top. The salty capers and acid snap of the cornichons work neatly with the soft cheese. It is hardly dinner, more like something to eat while watching a film.

Serves 2

potatoes 900g, large, yellow-fleshed

groundnut oil 120ml

cherry tomatoes 100g

cornichons 12

capers 1 tbsp

olive oil 3 tbsp

burrata 2 large balls

Set the oven at 180C fan/gas mark 6. Scrub the potatoes and cut them in half lengthways, then into long wedges. Toss them in the groundnut oil, then place in a roasting tin in a single layer, with as much space as possible between them. Roast for about 45 minutes, turning them over halfway through. They should be crisp and deep gold.

Dice or cut the tomatoes into small pieces and put them in a bowl. Cut the cornichons in half and add to the tomatoes. Stir in the capers and the olive oil. Slit the burrata open, then spoon over the tomato salsa and its oil. Eat with the chips.

James’s fideuà

Ten years ago, James introduced me to a recipe that has become, in our house, the most hungrily anticipated feast of all. Fideuà, a Valencian pasta dish, is cooked in the style of a paella, using a mixture of shellfish and tiny macaroni-type pasta. (Any very fine tubular pasta will work, such as stortini bucati, if you can get it.) Good though this mixture of pasta, tomatoes, clams and mussels is, the real celebration is turning a spoonful over to reveal the gloriously smoky, sticky crust that has formed underneath. This essential detail – it feels like winning a prize – will only form if we resist the temptation to fiddle, to poke and stir. It is that, as much as the seafood itself, that is the true feast.

Serves 4

onion 1, medium

squid 2, cleaned

olive oil 3 tbsp

garlic 4 cloves

tomatoes 600g

sweet smoked paprika 2 tbsp

saffron a generous pinch (optional)

pasta 500g, small, macaroni-type such as stortini bucati

chicken or fish stock 1 litre

large prawns 12, uncooked

clams 250g

mussels 12

Peel the onion and cut into small dice. Remove the tentacles from one of the squid. Cut the body sac into small dice and set aside. Cut the second squid into wide strips, removing and reserving the tentacles as you go.

Place a shallow pan over a moderate heat and pour in 2 tablespoons of the olive oil. When the oil is hot, add the diced squid and cook quickly, letting it sizzle and colour lightly on both sides.

Peel the garlic and slice each clove very finely, then add to the pan, still set over a moderate heat, together with a little more oil if needed. Chop the tomatoes, fairly finely, add them and all their juice to the pan, and cook for 2 minutes. Stir in the paprika, saffron (if using) and pasta. Let the pasta toast for a minute, then pour on the stock, season with salt, bring to the boil and leave to cook for 8 minutes, or until two-thirds of the liquid has evaporated. At this point do not stir again until a fine crust has formed on the base.

While the pasta cooks, warm the remaining tablespoon of oil in a shallow pan, add the reserved raw squid and the prawns and cook for 2 minutes, till lightly browned. Remove immediately.

Place the clams and mussels and the squid and prawns over the surface of the pasta, then make a loose dome of kitchen foil over the pan and leave everything to steam for 2-3 minutes, till the mussels and clams have opened.

Serve immediately.

Sweet potato and lentil ‘shepherd’s’ pie

A big, fat, golden pie.

Serves 6

For the filling

onions 450g (2 large)

olive or vegetable oil 3 tbsp

carrots 150g

garlic 2 cloves

red chillies 2

cardamom pods 8

cumin seeds 1 tsp

ground coriander 1 tsp

ground turmeric 2 tsp

tomatoes 350g

vegetable stock 500ml

red lentils 350g

spinach 350g

lemon 1 large

curry leaves 10

For the topping

potatoes 500g

sweet potatoes 1 kg

butter 50g

parsley a small bunch, chopped

Peel and roughly chop the onions, then cook them in the oil in a deep pan over a moderate heat for 15 minutes, stirring from time to time.

Cut the carrots into fine dice, peel and finely chop the garlic and the chillies (discard the seeds if you wish), then add all to the softening onions and continue cooking for another 10 minutes, until the onion is pale gold and translucent.

Break open the cardamom pods, extract the seeds within and grind them to a coarse powder. I use a pestle and mortar for the sheer olfactory pleasure, but an electric spice grinder will work too. Mix them with the cumin seeds and ground coriander and turmeric, and stir into the onions. Cut the tomatoes into small dice and stir into the vegetables, leaving them to simmer for a further 10 minutes until the tomatoes have released their juice.

Add the stock and bring to the boil, then lower the heat to a simmer, season and leave to putter away over a low heat. Check the liquid level from time to time: you want a decent amount of juice, so add some more boiling water if needed.

Cook the lentils in deep boiling water for 20 minutes, until they are just tender, then drain. Try not to let them fall apart. Stir them into the tomato mixture.

While the lentils cook, peel the potatoes and sweet potatoes, then steam or boil until tender. This is best done separately as they cook at different times. Drain and mash them together with a vegetable masher or food mixer. Add the butter, chopped parsley, and salt and pepper, and set aside.

Wash the spinach leaves and put them, still wet, into a pan over a moderate heat. Cover tightly with a lid and let them cook for a minute or two until wilted. Remove the leaves, drain them and squeeze out most of the moisture.

Set the oven at 180C fan/gas mark 6. Stir the spinach into the lentils, together with the juice from the lemon and the curry leaves, then transfer to a deep baking dish, about 24cm x 28cm. Spoon the mashed vegetables on top – they will sink a little but no matter – and bake for 25 minutes.

Roasting a chicken

A good bird, the thoughtfully seasoned pan juices and a roast potato or three is more than enough.

Roasting and resting

Leaving the bird in the switched-off oven for 10-15 minutes with the door ajar is all the attention it needs, but if the roasties need a few minutes longer then I usually bring the meat out and let it snooze on a warm dish, hidden under a crinkly tent of foil.

Basting

You can, of course, roast a chicken with nothing but its own fat. The flesh will be tender and the flavour pure. But it will lack the crisp, burnished finish and juicy flesh of a bird cooked with fat. Butter, olive oil, dripping and pork fat (Ibérico, from a jar) all do the job, though I regard goose fat as the most successful for achieving bronzed skin. I reserve it for special occasions. For “special occasions” read birds whose price makes you swallow hard at the butcher’s counter. My fortnightly chicken gets a mixture of butter and olive oil. One fat flavours and burnishes, the other moistens. The olive oil prevents the butter burning.

While the chicken roasts, baste it two or three times. Briefly open the oven door, tip the tin to one side and delve into the pan juices with a large metal spoon. Pour these over the breasts and legs, then close the door. The job should be over in less than a minute; you don’t want the oven to lose its heat.

Seasoning

Thyme is the herb I use most often here. I stuff wisps of it deep into the chest cavity and squeeze a couple of sprigs into the pinch-point between leg and breast. Some cooks suggest pushing a herb or spice butter under the skin so the flesh is moistened continuously, and it is something well worth doing, but I am clumsy enough to tear the skin occasionally, which then shrinks and the naked flesh dries out as it cooks.

Tarragon has a legendary affinity with chicken. I would chop its aniseed-scented leaves into the pan juices once the bird is cooked. This gentler warmth will release the herb’s fragrance. A squeeze of citrus juice will accentuate the aniseed notes.

A lemon is another possibility. For years I popped half a lemon inside the bird as it roasted and still do so from time to time. Mostly on a summer’s day, for the citrus spirit it imbues to the meat juices.

The roasting juices

Once the bird and its potatoes are out of the tin, we are left with a deeply savoury, shallow pool of chicken juices and a sticky, almost caramel-like goo of toasted sugars and aromatics. This is a concentrated essence that we can trickle over the meat as it is, or dilute with stock, wine or water to pour over the carved meat on the plate. Sometimes I stir in a glass of white vermouth or a dry and nutty sherry. Tarragon is the only soft-leaved herb I use in the gravy. About 20 large leaves is enough. This is also the only time I would add cream to the pan. Roasting juices, tarragon and cream being very much the Father, Son and Holy Ghost to a chicken.

A small glass of dry marsala, stirred in with a wooden spoon as the juices simmer on the hob, always reminds me of Christmas. White vermouth is less sweet, summery even. Once you have let everything bubble, correct the resulting liquid with salt, fine pepper and perhaps the merest squeeze of lemon.

The accompaniments

Over the years I have served stuffing alongside the meat. In my 20s it was sage and onion from a packet, then, once I knew better, a homemade version with sausage meat, sweet onion and fresh thyme. I rarely bother now, preferring stuffing that is cooked outside the confines of the rib cage, in a separate tin, allowing it to form a crust.

If I want a stuffing swollen with the juices from the meat then I involve a few new potatoes no bigger than a bird’s egg, briefly steamed, lightly cracked and cooked inside the bird. There are other starches worthy of our attention: pieces of sweet potato swollen with the hot fat from the pan; chickpeas, cooked within the bird then crushed to a rough mash. I have also eaten my Sunday roast with a buttery mash of potato and melted cheese, even pearls of giant couscous stirred into the cooking liquor to soak up the sticky brown goo from the pan. All delicious in their own way. But far from essential. That is the term I reserve for roast potatoes.

Roast chicken with roast potatoes and roasting juices

Serves 3-4

a free-range chicken 1.5-2kg

olive oil 2 tbsp

butter or goose fat 50g

thyme 8 small sprigs

bay leaves 3

garlic 6 plump cloves

potatoes 1.5kg

For the gravy

dry marsala or white vermouth 4 tbsp

stock 200ml

Optional

lemon ½

stuffing

Set the oven at 180C fan/gas mark 6. Choose your heaviest roasting tin. A solid vessel is less likely to buckle when you transfer it to the hob to make the “gravy”. Retrieve the bag of innards from inside the bird. (I can’t tell you how many times I have forgotten to do that.) You can add them to the stock if the mood takes you. Place the chicken in the roasting tin and season it inside and out with sea salt and pepper. (I prefer a coarse grind.) Rub the olive oil into the breast and legs, then massage the breasts, legs and wings with the butter or goose fat.

Put half the thyme and the bay leaves inside the chicken and tuck the rest round the bird. If you are adding stuffing or lemon, do so now. Add the garlic to the pan. You will barely detect it as such, but the toasted cloves will lend a deeply pleasing, mellow sweetness to the juices. When the oven is hot enough, put the chicken in the oven. A 1.5kg chicken will take about an hour; a 2kg chicken 90 minutes. During cooking, baste the bird two or three times with the contents of the pan.

While the bird is cooking, peel the potatoes and cut them into large pieces (about 45-50g each for me, but only you know what size you like your roast potatoes to be), then bring to the boil in deep, salted water. Once the water is boiling, let them cook for 10 minutes or until they will easily take the point of a knife. Drain them in a colander, then return them to the pan and give them a quick shake from side to side to rough the edges up. They will crisp lacily if their edges are frayed and bruised. Once the chicken has been roasting for 25 minutes, add the potatoes to the roasting tin, turn them over in the fat and continue cooking.

The bird is done when its skin is puffed and golden, the flesh firm and its juices run clear when the thigh is pierced with a skewer at its thickest part. When it is ready, remove it from the oven, cover loosely with foil and keep in a warm place. If you have potatoes to brown, return them to the oven, putting the temperature up to 200C fan/gas mark 7 and keeping a close eye on their progress. Watch that the pan juices don’t evaporate or burn. The potatoes will take up to 10 minutes. They should, rather neatly, be ready by the time the chicken has gathered its thoughts.

A few notes

To make the gravy: once the bird is resting under its foil, and the potatoes are out, place the roasting tin over a moderate heat and bring the juices to a bubble. Squeeze the creamy interior of the garlic into the tin and discard the papery skins, then mash them into the fat and aromatics with a spoon. Stir in 4 tablespoons of dry (secco) marsala or white vermouth such as Noilly Prat and the stock. Now, this is the crucial bit: as the liquid starts to bubble, scrape at the tin with a wooden spatula or spoon, loosening all the jammy, crusty bits of Marmite-like goo from the tin. These are the concentrated meat juices and caramelised sugars that will enrich your gravy. They are the very essence of the roast bird. Stir as the liquid bubbles, dissolving any deliciousness from the roasting tin as you go. Season generously and, if you wish, pour through a sieve into a warm jug.

Sausages and sauce

In a perfect world, I would make this a day before I needed it, leaving it to mellow overnight in its pan. (Ragù is always better for a night’s sleep.) But even ladled onto pasta or soft polenta the day it is made, this is a splendid alternative to the traditional minced beef ragù. The soul of a ragù is in the browning of the meat and onion. Take your time when softening both – the onions need to be a deep golden brown, glossy to the eye and sticky to the touch before you add the rest of the ingredients.

Serves 4

olive oil 4 tbsp

thick Italian sausages 8 (850g)

red wine 250ml

onions 3 medium

garlic 4 cloves

thyme 4 bushy sprigs

rosemary 4 bushy sprigs

bay leaves 3

fennel seeds 1 tsp

plum tomatoes 2 × 400g tins

For the polenta

water 500ml

milk 500ml

polenta 125g, fine, quick-cooking

double cream 100ml

butter 50g

parmesan 50g, grated

Warm 2 tablespoons of the olive oil in a large frying pan over a moderate heat, tear the sausages into small pieces and add to the oil. Leave to brown and lightly crisp, turning from time to time. The crucial point here is to let each piece of sausage meat brown before you move it, so you encourage a build-up of sticky (and very tasty) goo on the bottom of the pan. Lift the sausage meat out into a bowl, turn up the heat under the pan, then pour in the red wine. As the wine starts to bubble, scrape away at the bottom of the pan with a wooden spatula – stirring the sticky goo from the sausages into the wine. After a couple of minutes of bubbling, remove from the heat.

Peel and roughly chop the onions. Warm the remaining oil in a large, deep-sided saucepan or enamelled cast-iron casserole. Keeping the heat no more than moderately high, let the onions cook till translucent and starting to soften, stirring regularly. As they start to turn pale gold, peel, finely slice and add the garlic. Add the thyme and rosemary sprigs, the bay leaves and fennel seeds. Grind in a little black pepper, lower the heat and continue cooking till the onions are pale brown and very soft. Don’t hurry this. You should be able to crush them easily between finger and thumb.

Stir in the sausage meat and the red wine, then add the tomatoes and their juice and bring to the boil. Lower the heat to a very low simmer – the liquid should blip and bubble lazily. Partially cover with a lid and leave to cook for a good hour to 75 minutes. The occasional stir will stop it sticking to the pan. Should the liquid level drop, add a little water or stock.

For the polenta, put the 500ml of water and milk on to boil in a deep, high-sided pan. As it boils rain in the polenta. Season very generously with salt and bring to back the boil. Warm the double cream in a small pan. As the polenta thickens, pour in the warmed double cream, add the butter, then stir in the grated parmesan.

A Basque-style cheesecake

In San Sebastián with James, late winter 2016. After a standing lunch of grilled prawns and chilled fino, we followed the curve of La Concha Promenade, then wandered through the cobbled streets of Donostia. There was no plan, no tourist map in our hands. Just the assurance that should we get lost, it would be brief and perhaps it wouldn’t be such a bad thing anyway. Late in the afternoon – at my insistence – we stopped at a pasteleria for coffee and something sweet. A morsel to keep us going until our inevitably late dinner.

I chose a slice of cheesecake, its centre as soft as syllabub, its crust scorched. A cheesecake with no pastry or crumb crust to support its curds, no berries rippled through the deep, vanilla-scented custard. A cake that wobbled mousse-like on the fork. I was surprised not to miss the crunch of pounded crumbs. Not only was it not missed, the biscuit crumbs suddenly felt like an interference. Grit in the oyster. The smoky bitterness of the blackened crust was all the contrast I needed.

Back at home, I set about making a similar Basque-style cheesecake. I am used to keeping an eagle eye on progress, to ensure not a freckle of brown appears on my cheesecake’s surface. It took six attempts to perfect the wobble and char, but I think we are here now.

Serves 8

full-fat cream cheese 650g

caster sugar 220g

lemon 1

vanilla extract ½ tsp

eggs 4, plus an extra yolk

double cream 250ml

soured cream 150ml

cornflour 30g

sea salt a generous pinch

Set the oven at 200C fan/gas mark 7. Line the inside of a high-sided 20cm springform cake tin entirely with baking parchment, making sure you bring it up the sides. It will pucker around the edges, but no matter. Place a pizza stone or baking sheet in the oven to heat up.

Put the cream cheese and caster sugar in the bowl of a food mixer and beat for a few seconds until mixed. Grate the lemon zest into the cheese, then add the vanilla extract.

Break the eggs into a small bowl, add the extra yolk and beat lightly with a fork to combine the yolks and whites. Introduce the eggs to the cream cheese, beating at slow speed, then pour in the double and soured creams. Push the mixture down the sides of the bowl with a rubber spatula and briefly continue mixing. At this point it may look too liquid but worry not.

Stir in the cornflour and salt, making sure it is thoroughly combined, then pour the mixture into the lined cake tin. Slide carefully into the oven, place on top of the hot stone or baking sheet and bake for 45 minutes, until the cake has risen a little and its surface is dark brown. The centre may quiver when shaken. A thoroughly good thing. Now turn off the heat and leave the cake to settle for a further 10 minutes. Remove the cake from the oven and leave to cool, then place, still in its tin, in the fridge.

When completely cold, remove the cheesecake from its tin and serve in thick slices, perhaps with a small dish of extra soured cream.

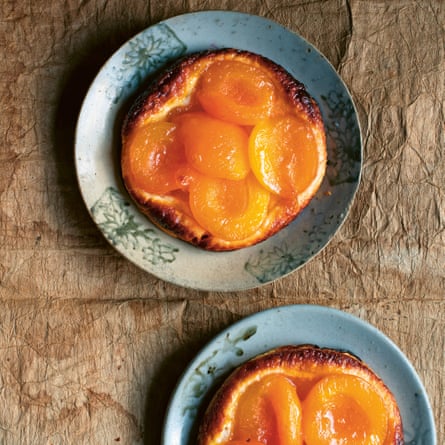

Quick apricot tarts

As a rule, tarts are filed under “serious cooking”. There is pastry to be made; baking blind to be done; fillings to be mixed; a glaze of some sort. Recipes that take hours rather than minutes.

Enter frozen puff pastry and tinned apricots. Commercial puff pastry is pretty good, especially (for which read “only”) if it is made with butter. Apricots survive the canning process better than most fruits – they can often be better than the fresh fruits you so carefully poach in sugar syrup. Tarts made using such everyday shortcuts still possess the crisp, buttery pastry and melting fruits you would get if you spent hours making your own puff pastry and preparing your own fruit.

Makes 4 tarts

apricots 10 fresh, or 20 tinned or poached in syrup

caster sugar 3 tbsp

puff pastry 320g

apricot jam 4 heaped tbsp

If you are using fresh apricots, halve and stone them, then put them in a small saucepan, add the sugar and enough water to just cover the fruit and bring to the boil. Lower the heat and simmer for about 10 minutes till the fruit is soft and tender. The apricots must be so soft you could crush them between your fingers. Drain them.

If you are using tinned apricots, drain them in a sieve over a bowl.

Set the oven at 200C/gas mark 7. Place a baking sheet in the oven to get hot.

Roll out the pastry to a rectangle 30cm x 23cm. (That is pretty much the size of a roll of ready-made puff pastry.) Using a 12cm-diameter template (a saucer or small plate or large cookie cutter), cut four rounds of pastry. Place each on a lightly floured baking sheet (lined with baking parchment if you wish). Score a wide rim around the outside of each one about 1cm in from the edge – I use a 10cm cutter for this – taking care not to cut right through the pastry.

Place the apricots on the pastry, four or five halves to each tart, steering clear of the rim. Slide the baking sheet on top of the hot baking sheet in the oven and bake for 10-12 minutes, till the pastry is puffed and golden.

Warm the apricot jam in a small saucepan. Remove the tarts from the oven and brush the jam over them, covering both fruit and pastry. Return to the oven for 3-4 minutes till the edges have browned and the glaze is just starting to caramelise. Let the tarts settle for 10 minutes before eating.

A Cook’s Book by Nigel Slater (4th Estate, £30). To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

The Observer aims to publish recipes for sustainable fish. Check ratings in your region: UK; Australia; US