- India

- International

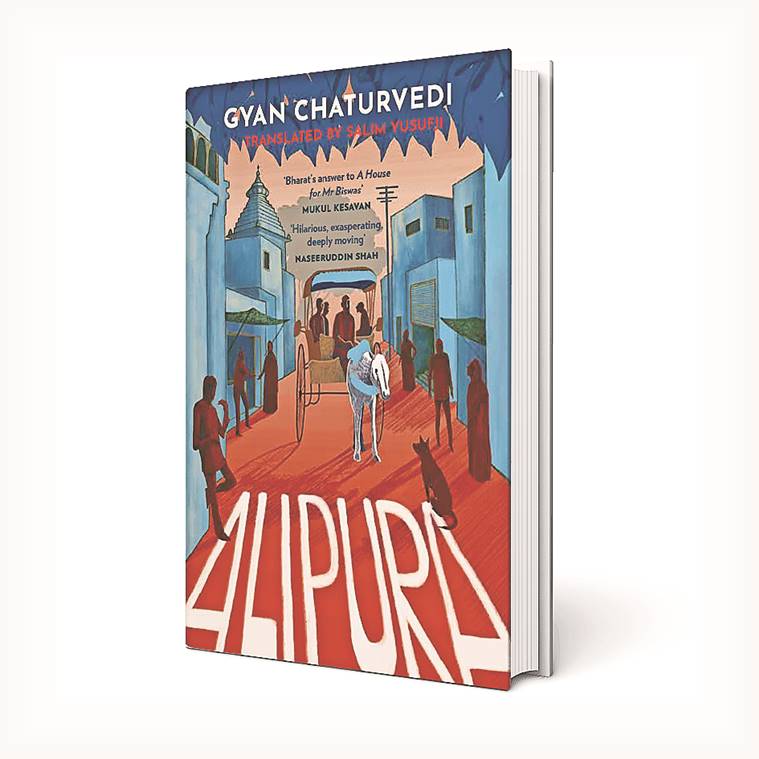

A new English translation of Gyan Chaturvedi’s Hindi classic satire Baramasi kindles nostalgia but labours emotionally

Translator Salim Yusufji has done a commendable job with Alipura, in deftly recreating a vanished way of life and character portrayals — but the tragic absurdity of their situation is lost in translation

Set in Bundelkhand, Chaturvedi’s novel Baramasi sparkles with a wit intrinsic to the language and culture it is located in. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Set in Bundelkhand, Chaturvedi’s novel Baramasi sparkles with a wit intrinsic to the language and culture it is located in. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)Gyan Chaturvedi is a Hindi writer of dazzling brilliance. His novels are often riotously funny. But they also open up windows to underlying existential tragedies. His first novel, Narak Yatra, was set in the corrupt world of Indian medical colleges, where the exercise of petty power is the raison d’etre of education, more than the healing of the body or enriching of the mind. The novel is like a dark Raag Darbari (Shrilal Shukla’s 1968 novel) of Indian education. There is a particular genre of Hindi literature that is hard to describe. It is not quite satire because it does not mean to mock. But it is not quite idle humour either. It is a form that is acutely realist in its descriptions. But it is laced with comic effect, not because it is making fun of reality, or because it makes light of human suffering. It is comic because characters use language that embraces a kind of absurdity. This is their way of holding onto meaning in a world that otherwise does not make sense.

Alipura, a translation of Chaturvedi’s classic Baramasi (1999), is the story of an impoverished family in Bundelkhand. It begins with the daughter of the family Binno waiting for an appropriate groom to accept her. But the canvas then shifts also to the lives of her four brothers: an older brother who cannot seem to bear the world, another who is waiting to pass an exam that forever eludes him; a third one, who seems to be both too clever by half and heading nowhere and a younger one whose studiousness might just allow him to escape into the middle class. But this is also the world of the sacrificing mother, some colourful relatives, and the town of Alipura as a whole.

Alipura by Gyan Chaturvedi; translated by Salim Yusufji; Juggernaut Books; 344 pages; Rs 599

Alipura by Gyan Chaturvedi; translated by Salim Yusufji; Juggernaut Books; 344 pages; Rs 599

In all his novels, Chaturvedi is a master of deft characterisation. But he also opens up a window to a whole social milieu. In this case, it is the town of Alipura, at the margins of history, where the passage of time is vicariously marked by Dilip Kumar being replaced by Dharmendra and then Dharmendra being replaced by Amitabh Bachchan on calendars.

In the translation, the title has been changed to Alipura, suggesting the novel is about a place, with all its texture and thicket of social relationships. This is a place where the ability to wield a lathi is a badge of honour and being a dacoit is an open social role, not a crime. Alipura is precise and evocative in its physical descriptions. It conjures up a whole world by placing telling details in all the right places. It is worth reading just for its recreation of a vanished world. But it is also deft in its portrayal of characters. For all their volubility, each of the siblings has a strange inwardness. Like the town as a whole, they are stuck in the gap between dreams and reality. In some ways, the novel is far more than just about a place. It is more about a condition than a location. This is, perhaps, something that changing the title of the book to Alipura might not quite capture. It is about the passage of time, where time changes, but little else does other than the slipping away of dreams. It is, above all, about lives that are marked by disappointment; the sense of not being

able to measure up to the norms of success or feeling wanted.

Alipura pulls off the interesting feat of suspending the reader between two contradictory dispositions. On the one hand, the social world the characters inhabit appear utterly meaningful to them; yet, there is a tragic absurdity to their situation that does not make sense. This split in the self is captured and managed through the medium of language. It is through language that drips with contemptuous wit that they can achieve a measure of freedom. Just the freedom to say as a character says at one point, “Chhodo raja, kaun saala harami nahin hain”, is an act of clarity that compensates for the sense of helplessness.

But this poses a problem for translators. So much of the force of Chaturvedi’s novels depends upon the cadence of the language, reading them aloud in Hindi produces an effect that is almost impossible to reproduce in English. Salim Yusufji has done a commendable job. But I must confess that Alipura is the kind of novel that runs up against the limits of translation very quickly. Take a small example. In the book, there is a hilarious moment. Chhuttan and Bibbo are two characters. The Hindi sentence goes, “Chhuttan tatha Bibbo ke beech gobar aa gaya aur sab gudgobar ho gaya.” Part of the effect comes from the play on “gobar” and “gudgobar”. But how do you translate this? Yusufji translates it as “the two piles of excreta should have intervened so forcefully and turned Chhuttan’s chances to shit.” It’s not exactly wrong, but it cannot capture the delicacy, alliterative power or existential irony of the Hindi novel. It is a cliché that all translations are incomplete or imperfect. But it is, perhaps, even truer of novels where the central character is language itself in all its rambunctious glory.

Alipura is worth reading in English for the access it gives to a vanished world and the lives of its characters. But, somehow, the emotional resonance of this sad and comic world feels a little more laboured in Englishthan in Hindi.

(Pratap Bhanu Mehta is contributing editor, The Indian Express)

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05