For years, as East Baton Rouge has sprawled south and Ascension and Iberville parishes have reached north, people have searched for ways to unclog the scenic bottleneck that is Bayou Manchac.

Hemmed in by low bridges and the occasional bulkhead, choked by sediment and debris, the bayou holds a key spot in Louisiana history, had once been intermittently tied to the Mississippi River and is the occasional grounds of wandering manatees. Now, it has become, by necessity, a utilitarian drainage outlet for suburban growth.

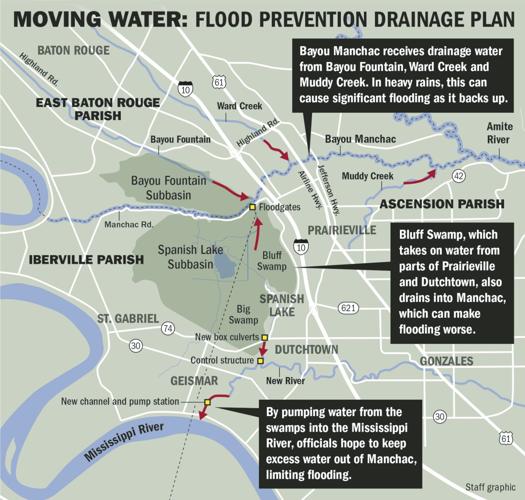

Trying to avoid the complications of clearing a wider path through Manchac east to the Amite River, people have often called for pumps that would drain the bayou west to the Mississippi River.

Cost has always been a stumbling block, however, for pumping plans that likely would need federal dollars, officials have said.

Though still very early, engineers working for Ascension Parish now say they may have found a plan to provide the long-sought back-door drain for the Spanish Lake region and, by extension, Manchac, as the August 2016 flood, repeated hurricane threats and the rains of May have focused attention on the region's drainage issues.

Ascension consulting engineers have proposed linking New River with the southern end of the Bluff Swamp at a chronic low spot at La. 74 and Bluff Road in Dutchtown. A new pump station at the Mississippi would draw water from the swamp through New River and a newly dug canal into the "big muddy."

Engineers with the Baton Rouge firm HNTB say the plan would take advantage of a natural link between New River and the Bluff Swamp that La. 74 is blocking and reduce swamp flood waters that must now wait in line — along with runoff from South Baton Rouge and eastern Iberville — to exit through Manchac to the Amite.

John Monzon, civil works manager for HNTB, told an Ascension drainage panel that the pump would allow the parish to better control water levels in Bluff Swamp and build up flood storage capacity in advance of big rains.

The eastern swamp of the huge Spanish Lake region receives runoff from Dutchtown, Geismar and Prairieville and is susceptible to high water from Manchac when it overtops a levee road.

That combination left homes in the basin stranded and flooded for weeks in August 2016 and again in May and has prompted dramatic but controversial emergency steps by Ascension and Iberville officials, like inflatable AquaDams and repeated cuts in the levee road, to protect people living in the swamp basin.

The new pump would also keep that water from having to get through Manchac in the first place, allowing water to drain more quickly out of Bayou Fountain in East Baton Rouge, Monzon said.

The new outlet and pump would also remove runoff from New River that now must travel 18 miles east through Geismar, Gonzales and St. Amant to Ascension's Marvin J. Braud Pumping Station, ultimately also keeping some water out of St. James and Livingston parishes downstream from those pumps.

A new control gate on New River would direct how much water heads east, how much heads west and prevent water from backing up into Bluff Swamp.

"We do believe this project will provide an immediate benefit to Ascension Parish and the surrounding parishes as well," Monzon said.

Lots of questions

The plan already has received mixed reviews from some Ascension officials. They want to see more work on the bayou itself that benefits northern Prairieville residents directly.

Councilman Corey Orgeron, who represents northern Prairieville west of Airline Highway, had a basic question for Monzon.

"What does that do for those districts that are residing along the Bayou Manchac? We're still going to get all this water from EBR, so there's no plan to protect the northern part of the parish with this effort," Orgeron asked last week.

Monzon said the New River pump would help Ascension along Manchac and west of Interstate 10 by reducing water in the bayou.

Under the leadership of U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, R-Baton Rouge, officials in Ascension, Iberville and East Baton Rouge also have agreed to look at other ideas to alleviate Manchac flooding.

They include at least one other pump station at the former Willow Glen power station near St. Gabriel that would drain Manchac directly, bayou clearing projects and the raising of low bridges over Manchac, Ascension and other officials have said.

Pumps directly tied to Manchac have been seen as prohibitively expensive because of the amount of canal dredging, wetlands destruction and home displacement necessary, but the officials are looking at alternative routes and at repurposing Willow Glen's discharge pipes over the Mississippi River levee to save money.

Details that might determine the future of the New River pump like construction cost, the amount of flood reduction and operations remain unknown. HNTB officials did not respond immediately to requests for comment.

Recent leadership and electoral turmoil on the East Ascension drainage panel that would pursue the project — likely through Louisiana Watershed Initiative funding — may also call into question what the body ultimate decides once HNTB finishes its analysis of the concept.

Days after sitting in on a presentation about the plan with the parish councilmen who make up the drainage panel, Parish President Clint Cointment received a notice on Thursday that he would be terminated as head of drainage. Six members of the panel face their own election recalls, including Orgeron.

Also, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers officials said the idea would also likely prompt an extensive permitting review because it will affect the hydrology of a large wetland area containing federal land banks set up to compensate for wetlands loss elsewhere in Louisiana. Ascension officials will likely have to come up with an operational plan regimenting the pump's operation, Corps officials added.

Bob Jacobsen, a Baton Rouge hydrologist who has been a part of past studies of Manchac, said a lot will depend on what kind of flood reduction HNTB can find from the proposal.

He noted other concepts, including a stalled idea in the mid-2000s to put a pump and floodgate across Manchac, just haven't shown the benefit necessary to compete for dollars and generate political momentum.

"The problem is … really understanding, you know, what drives the flood risk and where the flood risk is and what's going to change the flood risk is, obviously, complicated or people would have solved it long before now," Jacobsen said.

What about dredging?

Others say Ascension is leaving too many other stones unturned. John Rosso, a resident of the Belle Grove neighborhood in Prairieville, has been trying to gather support from surrounding neighborhood associations to press Graves and local officials on Manchac.

Rosso, 69, who spent a career in industry and doesn't like to hear what can't be done, said he doesn't understand why more hasn't happened on Manchac in the five years since the August 2016 flood sent nine inches of water into his house.

But he believes mechanical drainage methods like pumps should only be a last option after all natural solutions are examined.

"The natural flow of the terrain, in my view, is the best means to address the problem, alright? … But what I think is that we haven't yet taken and addressed those means to determine whether or not it's going to be satisfactory to meet the requirements of any 100-year flood," Rosso said.

That kind of work could require, Rosso said, dredging out the Amite from its mouth at Lake Maurepas north and then into Manchac.

On the other hand, people who study and manage the ecology of the Spanish Lake region said, at first blush, a New River pump might provide an important benefit that has been unrecognized in recent talks.

As growth has continued to sprawl around the swamp basin, more roofs and concrete have sent more runoff into the basin. Global climate change has also made rains more intense.

Both have acted to make flooding last longer and go higher in the swamp, an LSU coastal researcher said, and has simultaneously raised the average water level in Manchac by one-tenth of a foot per year since the 1970s.

Paul Kemp, who has studied the Bluff Swamp as LSU coastal sciences professor, said longer periods of flooding don't allow cypress and hardwood seedlings to take root. As old trees die, new ones aren't replacing them.

Anything that would reduce that flooding would help improve the forest's health, he said.

Scott Nesbit, who manages the 4,000-acre Spanish Lake Restoration wetlands bank in the Bluff Swamp, agreed with Kemp, saying the land bank would support the idea as long as the proposed Bluff and Willow Glen pumps are managed properly.

"SLR supports both projects which partially restore the historic, seasonal hydrologic regime that sustained the 17,000-acre forested wetlands for thousands of years," Nesbit said.

Also, Kemp and others noted, any major plan to dredge out Manchac ignores an important fact about flooding on the bayou.

Some of the worst flooding along Manchac happens from backwater in the Amite, which pushes water up the bayou and against its normal flow.

Work that improves the efficiency of Manchac to drain to the Amite will likewise improve the efficiency of Amite to send water back upstream, Kemp said.

"So," he said, "anything that we could … you know add another outlet somewhere is worth looking at."