- India

- International

MSP is not the way to increase farmers’ income

Ashok Gulati, Ranjana Roy write: Augmenting farmers’ income will require investment in animal husbandry, fisheries and fruit and vegetable cultivation. Private sector needs to be incentivised to create value chains

A better method would have been to look at average annual growth rates (AAGR), if yearly data was available. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)

A better method would have been to look at average annual growth rates (AAGR), if yearly data was available. (Illustration: C R Sasikumar)After two successive droughts in 2014-15 and 2015-16, Prime Minister Narendra Modi set out an ambitious target to double farmers’ incomes by 2022-23. Many analysts thought he was talking about nominal incomes. But the Ashok Dalwai Committee, which was set up to chalk out a strategy to achieve this, made it clear that the target of doubling farmers’ incomes was in real terms and the goal was to be achieved over seven years with the base year of 2015-16. It clearly stated that a growth rate of 10.4 per cent per annum would be required to double farmers’ real income by 2022-23. According to an estimate of farmers’ income for 2015-16 by NABARD in 2016-17, the average monthly income of farmers for 2015-16 was Rs 8,931. However, unless a similar survey is conducted in 2022-23, we won’t really know what happened to the target of doubling farmers’ real income.

We do have the recently released data for 2018-19 based on the Situation Assessment Survey (SAS) of agricultural households conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO). As per this survey, an average agricultural household earned a monthly income of Rs 10,218 in 2018-19 (July-June) in nominal terms. We have a similar SAS for 2012-13, when the nominal income was Rs 6,426. In nominal terms, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) turns out to be 8 per cent between 2012-13 to 2018-19. But we need to know the growth rate of real incomes. For that, the choice of deflator becomes critical. If one deflates nominal incomes by using CPI-AL (consumer price index for agricultural labour), which should be the logical choice, then the CAGR turns out to be just 3 per cent. If one uses WPI (wholesale price index of all commodities), the CAGR in real incomes turns out to be 6.1 per cent. This vast difference is just due to the choice of deflator. However, there is another SAS that the NSO conducted for 2002-03. Although the definition of agricultural household in that SAS was based on some area operated during the last year of the survey — replaced by minimum income earned from agriculture in the SAS of 2012-13 and 2018-19 — when one compares CAGR in farmers’ real income (deflated by CPI-AL) over 2002-03 to 2018-19, it turns out to be 3.4 per cent (and 5.3 per cent if deflated by WPI). Obviously, in such point-to-point comparisons, the situation in the base year and terminal year influences the growth rates dramatically.

A better method would have been to look at average annual growth rates (AAGR), if yearly data was available. The AAGR for agri-GDP is available and at an all-India level, between 2002-03 to 2018-19, it turns out to be 3.3 per cent — this is very close to the real income growth (CAGR) of 3.4 per cent for the same period. However, at the state level, the variation is much more as state agri-GDP growth is volatile and depends on the monsoon — this is especially true for states that have a much lower level of irrigation. For example, Punjab with almost 99 per cent irrigation cover, will have a much more stable income than say Maharashtra with just 19 per cent irrigation cover.

A disaggregated state-level analysis shows a huge gap between agriculture GDP and farmers’ income growth in many states — Kerala, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh. But a closer look at individual states indicates that the Gujarat region had a 27 per cent deficient rainfall than its Long Period Average (LPA) and Saurashtra, Kutch and Diu were 38 per cent rainfall deficient in 2018-19. Jharkhand had 31 per cent deficient rainfall, while Kerala experienced a major flood in 2018-19. No wonder, the agricultural GDP growth of Gujarat was negative (-8.7 per cent) in 2018-19. This would surely depress the farmers’ incomes in the state for 2018-19. But overall, for the period 2002-03 to 2018-19, Gujarat’s agri-GDP growth is 6.5 per cent — one of the highest in India. The upshot of this analysis is that at the state level, it is important to consider both the indicators (growth in agri-GDP as well as farmers’ incomes based on a survey of the specific year) to get a clearer picture of the state of affairs at the farmer level.

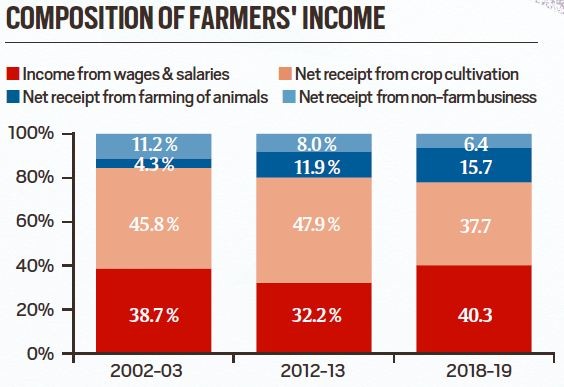

What is the policy message that one can derive from comparing these three rounds of SAS – 2002-03, 2012-13 and 2018-19? The figure gives the changing composition of farmers’ real income.

What is clear from this comparison is the following: One, the share of income from rearing animals (this includes fish) has gone up dramatically from 4.3 per cent in 2002-03 to 15.7 per cent. Two, the share of income from the cultivation of crops has decreased from 45.8 per cent to 37.7 per cent. Three, the share of wages and salaries has gone up from 38.7 per cent to 40.3 per cent. Four, the share of income coming from non-farm business has come down from 11.2 per cent to 6.4 per cent.

What these survey results indicate is that the scope for augmenting farmers’ incomes is going to be more and from rearing animals (including fisheries). It is worth noting that there is no minimum support price (MSP) for products of animal husbandry or fisheries and no procurement by the government. It is demand-driven, and much of its marketing takes place outside APMC mandis. This is the trend that will get reinforced in the years to come as incomes rise and diets diversify. Those who believe that farmers’ income can be increased by continuously raising the MSP of grains and government procurement, irrespective of the fact that grain stocks with the government are already overflowing and more than double the buffer stocking norms, are living in the past — and advocating a very expensive food system. That will fail sooner or later. Wisdom lies in investing more in animal husbandry (including fisheries) and fruits and vegetables, which are more nutritious. The best way to invest is to incentivise the private sector to build efficient value chains based on a cluster approach. The Narendra Modi government has started working in this direction, but much more needs to be done.

This column first appeared in the print edition on September 25, 2021 under the title ‘Not the MSP route’. Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Roy is a Research Fellow at ICRIER

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05