Students share ‘coming out’ experiences, celebrating LGBTQ+ history month

University of Iowa students reflect on their coming out stories as they celebrate National Coming Out Day and LGBTQ+ History Month.

Lillian Poulsen poses for a portrait in her apartment in Iowa City on Thursday, Oct. 7, 2021.

October 12, 2021

Trigger Warning: This article includes mentions of sexual assault.

I was 12 when I first thought I might be gay. I had just finished watching the “Starships” music video, which featured a semi-naked Nick Minaj, and I ran across the street to my best friend’s house to tell her.

“When you watch women in videos and stuff, do you feel kind of funny?” I had asked.

“What do you mean?” she said.

“I feel like I feel when I look at boys,” I told her.

She responded, “Oh, I think that’s just how everyone feels.”

At the time, I thought nothing of it. When she came out as bisexual nearly seven years later, I thought back to that day. I’d asked a bisexual person to help me confirm my heterosexuality — obviously, it didn’t work.

It wasn’t until over nine years later that I would come out to some of my family members and my closest friends. While my thoughts seemed natural for a straight woman at the time, I spent the next nine years considering the same questions, with virtually no one to tell.

I grew up in a Christian household that told me any sexual thoughts outside of marriage — never mind gay ones — were not only inappropriate, but sinful. For nearly a decade after I had my first gay thought, I sat hiding in a closet my parents had built for me.

National Coming Out Day was Monday. This is the annual LGBTQ+ awareness day to support LGBTQ+ people “coming out of the closet.” October is also LGBTQ+ History Month, an annual observance of queer history and related civil-rights movements.

For me, though, coming out wasn’t some joyous experience that other LGBTQ+ people get to have — and I’m not the only one who felt the coming out process was negative. Over a third of LGBTQ+ people feel the same way I did when I came out, according to a 2018 survey from Bespoke Surgical.

My coming out experience was one that happened quickly — my parents pushed my announcement aside before I could even get the words “I’m bisexual” out of my mouth.

I came out to my parents earlier this year, in a devastating and surprising way. I told my mom, who grew up with conservative Christianity at the forefront of her life, that I might like women. I couldn’t make myself tell her that this wasn’t a confusing thought, but rather something that I had thought about since before I knew how sexual attraction felt.

My mom told me I was confused and that liking women was just a phase for me. This was hard to hear, especially because I knew I had felt this way since my adolescence.

My coming out experience ended up being overshadowed by my own physical and mental health, but my parents didn’t take it seriously. While I had summoned the courage to tell my mom, I didn’t tell my dad. As with most other secrets in my life, I waited until my mom told him.

RELATED: Different groups of people come forth about mental struggles and barrier to treatment

While I battled health problems and worried about being out in a family that would never fully accept me for who I am, my sister was figuring out their own coming out story.

One day, while my parents looked through my phone, they saw text messages between my sister and me that detailed a relationship my sister had with a woman. My dad later confronted them, blindsiding them with the news and meeting their expectations of being homophobic rather than loving.

Annalyn Poulsen, my sister and a second-year creative writing major at the University of Iowa, said their experience with coming out didn’t allow them to tell our parents.

“It didn’t feel like coming out, it felt more like I was outed,” Annalyn said. “I had a conversation with my father about it, and he kind of eased into it so I didn’t know what he was going to talk about.”

Annalyn’s experience was a negative one, in which our dad invalidated their feelings and explained the problems with being a lesbian.

“He said to me, ‘The thing about gay people is that they’re confused,’” Annalyn said. “He told me he had seen messages about me being gay and said I was just confused and didn’t know for sure.”

Our dad went on to say that being gay goes against nature, citing the AIDS epidemic, which killed 448,060 Americans between 1981 and 2000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“He said he didn’t agree with it, but he wasn’t concerned because it’s just a phase,” Annalyn said. “He also compared it to him being liberal for a large part of his life before realizing he was conservative.”

Annalyn said the only things they could to my dad, a man who is firm in his beliefs and won’t change his mind for anyone — including his two daughters.

“I said, ‘I don’t agree with that, but OK,’” they said. “All I knew was that he wasn’t going to kick me out, which is what I was worried about.”

Annalyn said they haven’t had a conversation with our dad or mom about sexuality since that day, and our dad will sometimes act like it didn’t happen. Even after my sister came out in May, my dad continues to ask them if they have a boyfriend.

Because of the way it happened, Annalyn said they will have to come out again once they’re in another relationship, telling our parents that they are dating a woman.

Despite having a negative experience with our parents, Annalyn had a positive experience when telling our brothers, one of our cousins, and me. They felt especially happy when they came out to many of their friends in high school, learning that many of them were also part of the LGBTQ+ community.

Like me, the first time my sister questioned their sexuality was middle school. It wasn’t until college that they realized they were lesbian.

“I thought I might be asexual, because my sister — you — told me what it meant. When I started high school, I watched a lot of YouTube videos featuring bisexual people which led me to thinking I was bisexual,” they said. “I started to explore my sexuality more and came to terms with it my junior year of high school.”

While my sister and I didn’t have a traditional coming out experience with our parents, every experience is different for each LGBTQ+ person.

Zarina Cornell, a first-year student in the UI REACH program, said she came out when she was 17. Before that, she didn’t know what being part of the LGBTQ+ community meant.

Like Annalyn and me, Cornell said her first queer experience was when she was 12. She said the first person she told was her brother, who later told their mom. However, she said she had a positive experience after telling her brother and dad.

“I never knew what being gay was or if it was seen as the norm,” Cornell said. “I always pressed those feelings down in my head and my heart, and I had a lot of sleepless nights.”

While Cornell realized she was a lesbian in high school, it wasn’t until college that she felt comfortable expressing her more feminine side and embracing her identity as a transgender woman.

For Annalyn, it wasn’t until their freshman year of college that they felt comfortable telling people they identify as non-binary and use she/they pronouns. Despite feeling comfortable in this identity with their friends, Annalyn said they don’t think they’ll ever feel comfortable telling our parents.

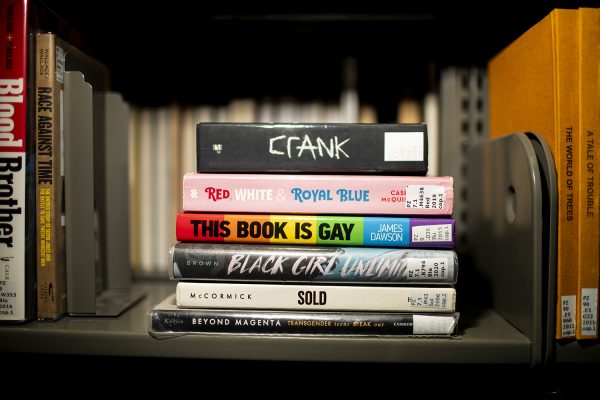

RELATED: Coming Out: University of Iowa students share their stories

Cornell said the first sexual experience she had with a man wasn’t pleasant, resulting in a traumatic sexual assault.

Cornell isn’t alone in this experience as a transgender lesbian. According to The Human Rights Campaign, LGBTQ+ people face high rates of poverty, stigma, and marginalization, which puts us at a greater risk for sexual assault.

Forty-four percent of lesbians and 61 percent of bisexual women experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner, compared to 35 percent of straight women, according to The Human Rights Campaign. Additionally, 26 percent of gay men and 37 percent of bisexual men experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner, compared to 29 percent of straight men.

While Cornell’s experience with coming out was scary at the time, she said she feels much more confident in her identities now and safe to be herself. She is especially grateful that she has friends and family accepting her for who she is.

No matter where someone is in their coming out journey, it’s important for people to check-in with themselves and the people they love. While I was scared telling my parents, I knew my community of friends, especially those who identify as LGBTQ+, would embrace and love me.

The most important thing to consider when coming out is timing, Cornell said. Although it can take a while, patience is crucial when telling family and friends, she said.

“Don’t rush it because it could lead to regrets,” Cornell said. “Coming out is not for your friends or family or anyone else, it’s for you and only your business.”

Although my parents may never understand my sister and me when it comes to gender and sexuality, we are both happier and more ourselves than we could be hiding in the closet.

The university offers a variety of resources to help people in the LGBTQ+ community. People who are struggling or looking for a community can find resources here.