What do Hollywood actor Humphrey Bogart, Senator Mitt Romney and half the US presidents have in common?

They are all alleged descendants of someone involved the 1692 Salem witch trials, in which an infamous outbreak of religious hysteria resulted in 19 early settlers hanged and one pressed to death.

Salem, Massachusetts, is America’s Halloweenville.

Every October thousands of tourists in costume flood the streets, buying “spell books” and snapping selfies in cemeteries.

Behind the shops, almost entirely divorced from the town’s main industry, lies the memorial with 20 stones carved with familiar names like John Proctor and Rebecca Nurse, who were immortalised in Arthur Miller’s 1953 “red scare” parable, The Crucible.

Alongside the tours, however, are a growing stream of visitors from as far as California paying their respects.

One card left in September for Susannah Martin, a 70-year-old impoverished widow from Buckinghamshire, England, executed for “bewitching oxen”, came from her alleged nine times great-grandchild, Riley.

They wrote: “I have felt the sorrow, pain, magic and power in Salem in myself. Unbeknownst to me I [had] three grandmothers buried in these grounds the whole time.”

An estimated 15 million Americans could claim a connection to the 329-year-old tragedy, according to the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), with millions more traceable to others accused of similar “crimes” in the 17th-century colonies, including New York and Connecticut.

For hundreds of years they were a source of shame. Nathaniel Hawthorne, the author of the 19th-century novel The Scarlet Letter, altered his name to distance himself from his great-great-grandfather, a Salem judge.

But recently, those who are descended from the accused witches have claimed the connection with pride.

“Witches are icons of early American history,” said Brenton Simon, president of NEHGS, founded in 1845.

The historian, who is indirectly related to three accused witches himself, added: “Alongside being descended from the Mayflower, witches are highly desirable ‘target’ or celebrity ancestors. People yearn to be related to them.”

Terry Koch-Bostic, the National Genealogical Society’s education chair, said Americans’ interest in witch ancestors relates to a history of “a country founded largely on immigrants whose stories were question marks, so we’re all looking for something that makes us special.”

She said heritage digging kicked off in earnest in 1976 after Alex Haley’s Roots, followed by the internet and digitised archives since the 1990s, cheap DNA testing since the 2010s, social media, and TV programmes like Who Do You Think You Are.

Europe executed thousands more “witches” than America, but due to largely piecemeal record-keeping until the 19th century, compared with fastidious New England records since the 1620s, and an unusual number of first-hand accounts of the trials, more Americans can prove lineage.

In the last few years it went mainstream.

Tourism organisations offer holidays to places where “witches” were murdered.

In 2017 Teen Vogue ran a story titled: “How to tell if your ancestors were witches.”

In the Facebook group Bloodlines of Salem, which has more than 2,000 members, hundreds of “cousins” commune over allegedly mutual ancestors.

Under a post about the sale of Proctor’s former home, 200 “relatives” debated crowdfunding its $750,000 purchase “so we can all take turns living in it. Lol.”

More rigorous lineage organisations like Son of a Witch, founded in 1975, or Associated Daughters of Early American Witches (ADEAW), founded in 1987, issue certificates and pins featuring witches or black swans, if applicants provide strict historical proof.

It took Lindsay Perodeau, 36, from Natick, Massachusetts, six years to get ADEAW membership, after accidentally discovering while looking for Mayflower relatives that Susannah Martin was her ninth-time great-grandmother.

She confirmed it through online and paper archives.

As a child in 1993 she was “obsessed” with Disney’s Salem film, Hocus Pocus, starring Sarah Jessica Parker, who also discovered a ‘witch’ relation, Esther Dutch Elwell, in 2010.

Perodeau added: “It’s amazing to be related to such a famous piece of American history. I feel proud that Susannah was clearly a feisty lady … I see my mom in her.”

The “daughter of a witch” certificate hangs in her house.

“Some people laugh: ‘You’re a witch?!’” she said. “I say: ‘No, I’m not making potions. No potions!’”

Some academics suggest the revival is a by-product of far-right attacks on women’s rights.

In 2019 the New York Times announced: “Witches are having a resurgence among feminists who want authority over their lives.”

“WitchTok” on TikTok also reportedly helped inspire the popularity of modern witches, or wiccans, with the now ubiquitous phrase “we are the daughters of the witches you didn’t burn” emblazoned on T-shirts (although US witches were hanged).

Many of the women convicted of witchcraft were considered outspoken and fairly independent, including women working as medical practitioners, Dr Amy Smith, Salem State University’s media professor, said, so contemporary women could “graft modern values of feminism on to pious and fairly powerless women”.

“It helps,” she added, “if it ‘confirms’ something you already believe about yourself, like: ‘Yes! I’m a fighter too!’”

And while historians continue to make discoveries, including Salem’s gallows site in 2013, critics accuse the town of “social amnesia”, especially after the 2005 unveiling of a statue of Samantha from the 1960s sitcom, Bewitched.

Richard Trask is related to several victims, including Mary Estey, from Norfolk, England, who was hanged aged 58.

He’s the archivist for Danvers, the original Salem Village outside modern Salem and site of the first accusations, before changing its name in 1752.

Trask said the confusion between “Halloween’s Disneyland and innocent people being murdered” had led to a “misrepresentation” that all victims were witches, citing wiccans holding ceremonies at Danvers’ memorial.

He added: “They were mostly Christians persecuted by other Christians, who died rather than admit to witchcraft. They would be horrified.”

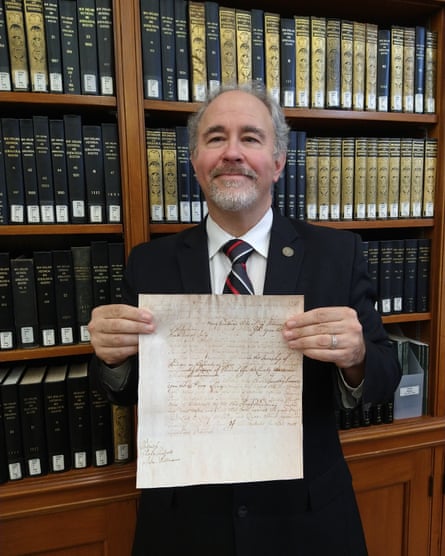

For David Allen Lambert, it doesn’t matter so long as the victims aren’t forgotten.

The chief genealogist for NEHGS is unusual in that he’s related to both a Salem victim, his eighth great-grandmother Mary Bradbury, from Warwickshire, England, who was convicted but escaped execution, and a judge, his seventh great-uncle Samuel Sewall, the only magistrate to publicly apologise.

“It was the darkest time in Massachusetts’ history,” Lambert said.

“It echoes today, what happens when disinformation spreads and neighbours turn on neighbours. We should remember our ancestors, not glorify their suffering. In my family none of our children have ever dressed as a witch at Halloween, out of respect for Mary.