- India

- International

Gujarat: The myth of a vegetarian state

Ghanshyam Shah writes: When we talk about vegetarianism and Gujarat, we are really talking about a very small section of society, whose world view is transferred and imposed, and later gains popularity and spreads.

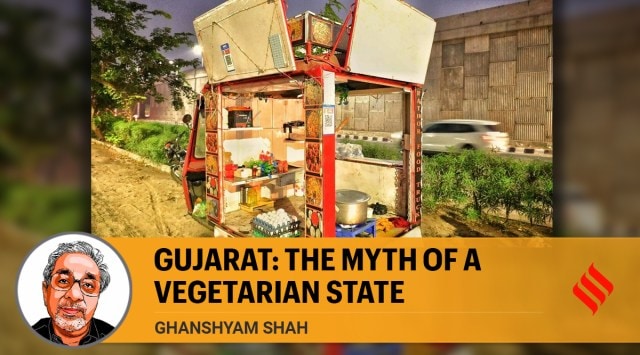

An eggstall in Ahmedabad, where many such kiosks were removed. (Express photo/Nirmal Harindran)

An eggstall in Ahmedabad, where many such kiosks were removed. (Express photo/Nirmal Harindran)It would not be incorrect to say that Gujarat’s geography has impacted its cuisine. Gujarat has a long coastal length of more than 1,250 km, and a rich history of trading with the outside world. Then, towards the east is the tribal area. As a row brews over non-vegetarian food stalls in the state, the truth is there is a wide variety among the food habits of tribals, the fisherfolk along the coastal areas and those in central Gujarat. Similarly, the fertile South Gujarat has altogether different food habits from the North, which is dry and arid.

During the pre-colonial period, the state was ruled by a number of small princely states, and areas that saw Mughal dominance. The parts inhabited by the Koli, Bhil tribals etc were isolated. However, the different regimes that ruled the state were not monolithic — they largely focused on collecting revenue and left the people to themselves. This meant that till early 19th century, Gujarat was a pluralistic society. One proof of this is that more than 20% of the words in the Gujarati vocabulary have roots in Persian and Arabic. The first history of the state, Gujarat No Itihas, was written in Parsi.

The food found across the state is no different, being an amalgamation of different tastes. The first attempt at “homogenisation” by a regime, which made it simpler to govern the people, was made during the colonial period. Questions by the Census and gazetteers demanded that people identify themselves with a particular structure. One of those who labelled Indian history as “a Hindu period” and “a Muslim period”, “an Islam period” and “a British period” was John Mill, who had never visited the country.

The beneficiaries of this British rule and demarcation were obviously those in business and the upper strata of society — the Brahmins and Baniyas — who were already several steps ahead when it came to education. As their influence increased, they also reconstructed the history of Gujarat as they perceived it.

Today, when we say Gujarat is a vegetarian state, I recall my own experience. I come from an upper strata of society, from the relatively vegetarian Vaishnav community, where even eating eggs is a taboo. Around 70 years back, when I was young, my father gave me eggs because they were good for health, inside several layers of wrapping. I would go to the roof of our building or pol to eat them.

Today, when we say Gujarat is a vegetarian state, I recall my own experience. I come from an upper strata of society, from the relatively vegetarian Vaishnav community, where even eating eggs is a taboo. Around 70 years back, when I was young, my father gave me eggs because they were good for health, inside several layers of wrapping. I would go to the roof of our building or pol to eat them.

My understanding of Gujarat growing up was that it was a kind of samaj. Today when you ask a Gujarati what is a samaj, they invariably talk about their caste. Therefore you see the Patidar samaj, Kshatriya samaj and others. Similarly, when you talk about Gujarat or Gujarat’s food habits or business, invariably we talk about the perceptions of the upper strata of society, mainly the Brahmins and Baniyas and very lately the Patidars.

However, even between them, there are variations — between the Nagar Brahmins, who were writer-advisors in courts, and the Anavil Brahmins of South Gujarat, who were largely tillers and are often called “Khato-Pito Brahman” as they eat and drink without inhibition.

According to a study by anthropologist K S Singh, with which I was associated, only about 26% of Gujarat’s population is actually “pure vegetarian” — meaning they never eat eggs or meat — and most people are better classified as “frequent vegetarians” and “frequent non-vegetarians”. When I was in college, I spent a couple of sleepless nights once over a Brahmin friend eating omelette! The fact also is that while they classify as non-vegetarian, many communities in Gujarat, including Muslims and tribals, can hardly afford meat regularly in their meals.

When we talk about vegetarianism and Gujarat, we are really talking about a very small section of society, whose world view is transferred and imposed, and later gains popularity and spreads.

Gujarat has seen the influence of both the Bhakti and Sufi movements, which were egalitarian. However, the later movements, such as of the Swaminarayan sect, were Brahminical and impacted food habits. They found their first followers among the Baniyas or the Vaishnavs. In fact, even Mahatma Gandhi blessed a movement that encouraged that the Panchmahal Bhil tribes be recognised as “backward Hindus” rather than as Adivasis. Another example are the Machhimaars who, through co-option, have been made to feel guilty about their traditional food habits.

Among others who eat non-vegetarian food too, there is a moral cost attached, with meat or alcohol to be shunned on “auspicious” days.

Interestingly, a survey in 2016 found that people in Gujarat who identified themselves as non-vegetarian outnumbered those in Punjab and Haryana, which make no boasts or claims about being vegetarian states. As Chief Minister, Narendra Modi did not venture into this territory (in fact, he belongs to a caste in which non-vegetarian food is traditionally not taboo), and this is perhaps why BJP chief C R Paatil and CM Bhupendra Patel have played down calls for action against non-vegetarian stalls along main roads in cities.

The writer is a political sociologist. As told to Ritu Sharma

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05