EVERETT – It’s called “The Wall” and it could help thwart cybersecurity attacks that threaten us all.

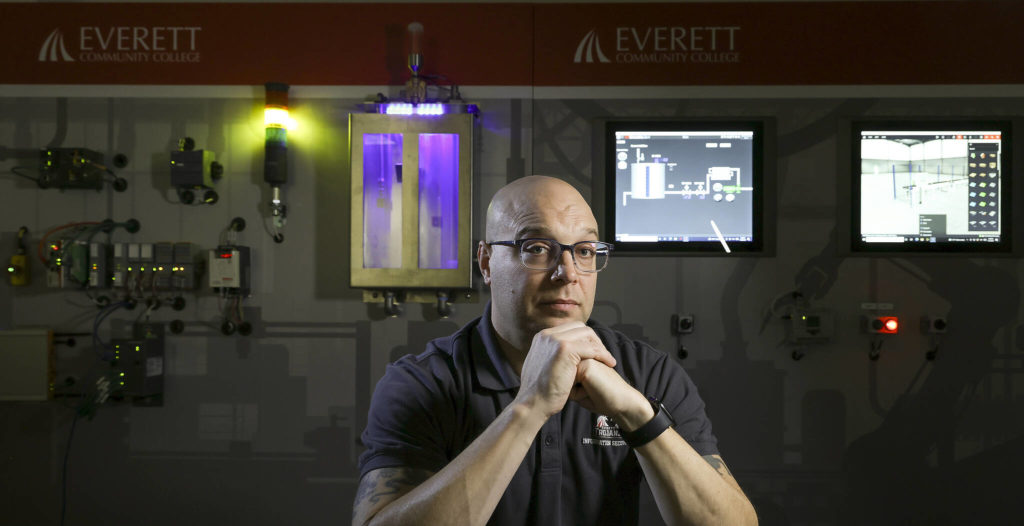

Everett Community College’s newest tool is a 6-foot-tall, 15-foot-long $500,000 interactive machine that’s being used to train a new generation of students for jobs in cybersecurity.

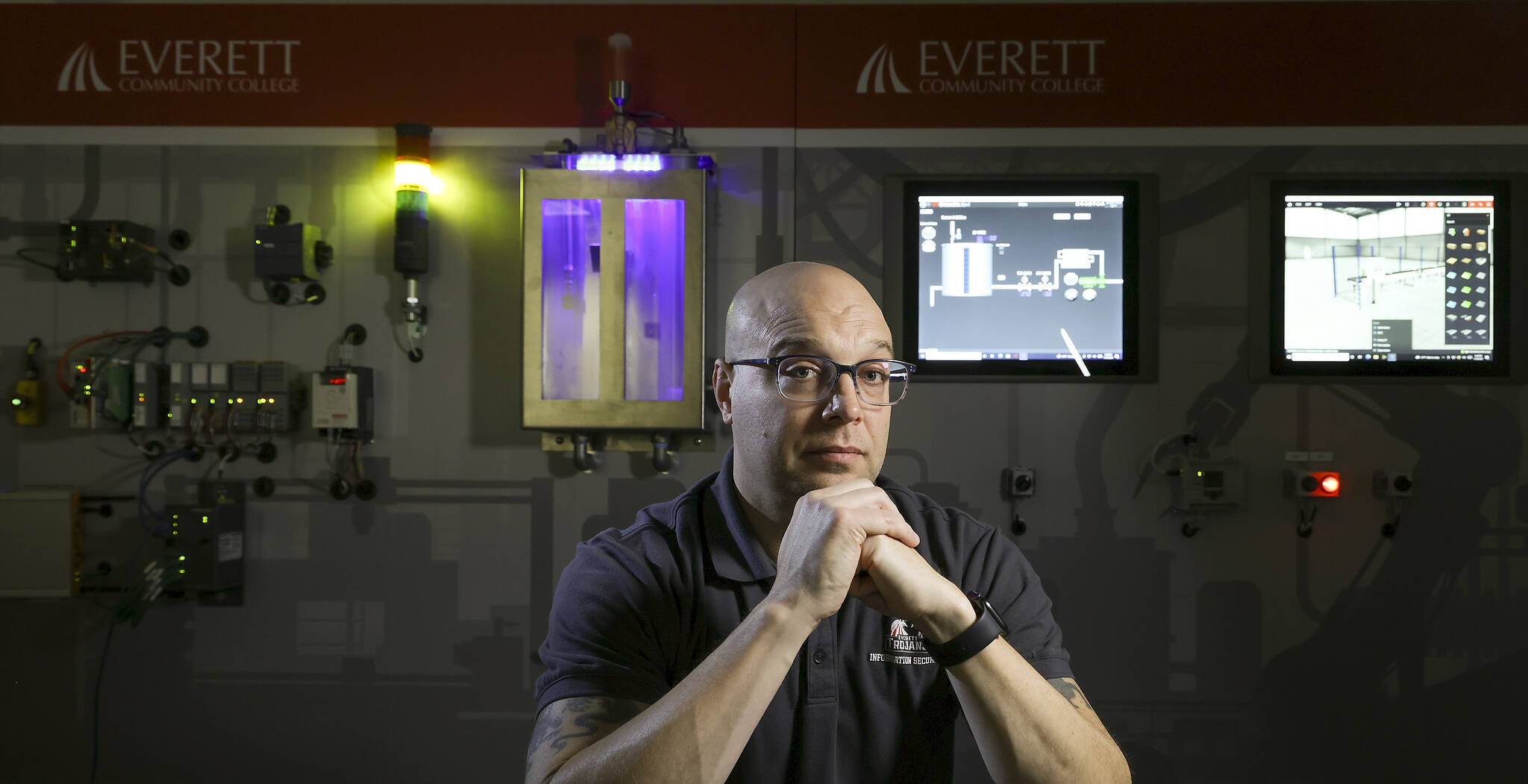

Students can use the industrial trainer to control the system, spot vulnerable points and even hack it themselves, said Dennis Skarr, information technology instructor at Everett Community College.

Here’s where it gets rad: The Wall has real pumps, water tanks, valves and electrical circuits that can be programmed to simulate the workings of a water treatment plant or an assembly line, for example, and the software that controls their functions.

The equipment can be used to model real-world cyber attacks and create a hands-on experience for students, said Skarr, who teaches cybersecurity classes at the college.

“We can’t do it exactly, but we can wing it and make it fairly accurate,” he said.

Lately, those types of cyber threats are hitting close to home.

In February, a cybersecurity attack rattled local authorities. The city of Lynnwood disclosed that the third-party company it uses to bill utility customers had been targeted by cyber criminals.

The Seattle-based payment processor detected the data breach when its servers were seized by ransomware. The malicious software holds hostage an organization’s files, making them inaccessible. To unlock them, cyber criminals usually demand a ransom.

The Port of Everett, the Alderwood Water & Wastewater District and the cities of Monroe, Kirkland, Redmond and Seattle were among those affected by the “Cuba ransomware” gang, the alleged culprit.

Although authorities concluded it was a relatively low-level threat, it was a reminder of how vulnerable computer networks can be.

Data theft is nothing new. It’s been happening since at least the late 1990s, said Skarr, 45, who received his cybersecurity training while serving in the Washington Air National Guard.

“How many times have you received a letter saying your personal information has been compromised?” Skarr said.

But while data breaches are old hat, the attacks are picking up in frequency and severity, Skarr said.

The latest scourge are cyber attacks that target physical infrastructure — pipelines, power grids, schools and hospitals.

Such strikes can inflict millions of dollars in damage and put thousands of people at risk.

Skarr believes The Wall could teach students how to guard against those threats and make students more marketable in today’s workforce.

Similar machines are usually available only to experts at cybersecurity seminars, Skarr said.

Everett Community College is the first community college in the nation to incorporate an industrial trainer into a cybersecurity program.

The Wall

Software-only simulations have value, “but nothing really beats the real thing,” Skarr said, standing in front of the industrial trainer that’s installed inside an EvCC classroom.

“One of the things you can do with this system is disrupt the equipment in ways that are more realistic and can’t be duplicated with a software simulation,” Skarr said, as he flipped a virtual switch and watched water flow into a tank.

The apparatus and EvCC’s expanded cybersecurity program were funded by three grants through the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges: a $78,000 Workforce Development Technology Enhancement grant and two Career Launch grants totaling $1.3 million. GRIMM, a national cybersecurity firm, developed the training wall.

Information Technology students at EvCC began using the device last spring. But students aren’t the only ones lining up to take advantage of the new technology.

The Washington State Guard’s cyber-protection team is using the trainer. And local business groups and IT divisions are asking for demonstrations, Skarr said.

Steven Hellyer, Information Technology director for the city of Everett, said the city and other local municipalities hope to launch a program using EvCC’s industrial trainer.

“We envision a program for IT professionals that addresses the common threats we all deal with,” Hellyer said. The threat list includes potential cyber attacks aimed at water control systems, fire, safety and transportation networks — critical infrastructure, Hellyer said.

As automated control systems become more widespread, protecting them would be the focus of the training, Hellyer said.

“Industrial control systems perform automated functions such as regulating chlorine levels or help with manufacturing and production,” he explained.

In the past 10 years, cyber attacks aimed at critical infrastructure networks have “substantially increased,” he said.

This year in particular, ransomware attacks targeting utilities, private manufacturers and hospitals have skyrocketed.

During the first six months of 2021, there were more than 305 million attempted ransomware attacks compared to 306 million attempts in all of 2020, according to a mid-year 2021 SonicWall Cyber Threat report. Some three-quarters of those attempts targeted U.S. organizations, the report said.

“It’s gotten so bad that insurance companies are raising their rates on cyber liability coverage or dropping coverage altogether,” Hellyer said. “This sort of training is very important to our national and local security and economic interests.”

Low-tech hacks

In May, hackers commandeered the largest fuel pipeline in the United states. They shut it down for five days, roiling East Coast fuel deliveries. To regain control, the Colonial Pipeline Company reportedly paid a $5 million ransom.

Despite the high price, Skarr called it a low-level break-in. The perpetrators didn’t actually hack the system or use password-cracking tools, he said.

All it took to break into the firm’s computer network was a password that had been compromised and leaked to the dark web, a part of the internet where users can hide their activities.

Password in hand, attackers penetrated the network using a company account that allowed authorized employees to remotely access the network, Skarr said.

And the threat doesn’t always end when the ransom is paid. Companies that fork over the money are often the target of repeat attacks. Eight out of 10 are hit again, according to a ZDNet, a business technology news website.

In June, a ransomware attack shut down meatpacking operations at JBS USA, one of the world’s largest meat producers. With factories idled in the U.S., Canada and Australia, the company paid an $11 million ransom to hackers, which the FBI identified as having links with Russia.

Hundreds of U.S. hospitals were mercilessly attacked this year by hackers, according to a Wall Street Journal report. Perpetrators “do not care,” hospital officials said.

The network attacks interfered with ambulance services and devices that monitor patients’ vital signs. In all, cyber-thieves extorted more than $100 million from 235 U.S. health care facilities, the report said.

Skarr and others believe the number of assaults may be much higher. “Not all are publicly reported,” Skarr said.

In a world rife with cyber threats and ransomware attempts, even small manufacturers and small utilities need to identify where their networks are vulnerable, Skarr said.

“The Wall can help identify some of the gaps,” he said.

Outcome unknown

Chris Von Reybyton tried out The Wall this spring when he enrolled in a class taught by Skarr that focuses on protecting physical infrastructure.

While software-only simulations can reveal how a cyber attack unfolds, “it’s all theoretical and very regimented,” said Von Reybyton, a former chef who graduated from the school’s cybsecurity program.

“You go from point A to point B. You know what the outcome is supposed to be,” he said.

“The great part of working with The Wall is you’re physically involved with something you’d face in real life,” he continued. “There is no point A to point B, so you don’t always know the outcome.”

During the spring session, Skarr based the class around the Oldsmar, Florida, hack, a cyber attack that compromised the city’s water treatment plant.

In February, a plant operator there observed “a cursor being moved around on his computer screen, opening various software functions that control the water being treated,” according to a report by Pewtrusts.org.

The network intruder raised the amount of sodium hydroxide (lye) used to de-germ the water supply to potentially toxic levels — about 100 times above normal. Fortunately, the intrusion’s discovery and multiple safeguards that protect the treatment process meant no damage was done, Skarr said.

Skarr’s exercise, said Von Reybyton, “illustrated the point that if you have really poor security, infrastructure attackers can easily break in.”

Routine software upgrades and lax business practices can also create security gaps that hackers can take advantage of.

Each software upgrade can introduce new vulnerabilities in a computer network. Organizations that fail to terminate an employee’s credentials or change a group password when they leave, “is like building a six-foot fence around your house and then leaving a seven-foot ladder next to it,” Skarr said.

The Wall will take center stage next spring when EvCC launches a new cybersecurity competition, open to college and high school students. To introduce the technology and give entrants practice time, the college plans a series of workshops.

“The fact that Everett Community College is the first community college in the nation to have this is amazing,” Von Reybyton said. “College and high school students will be able to use this.”

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097; Twitter: @JanicePods.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.