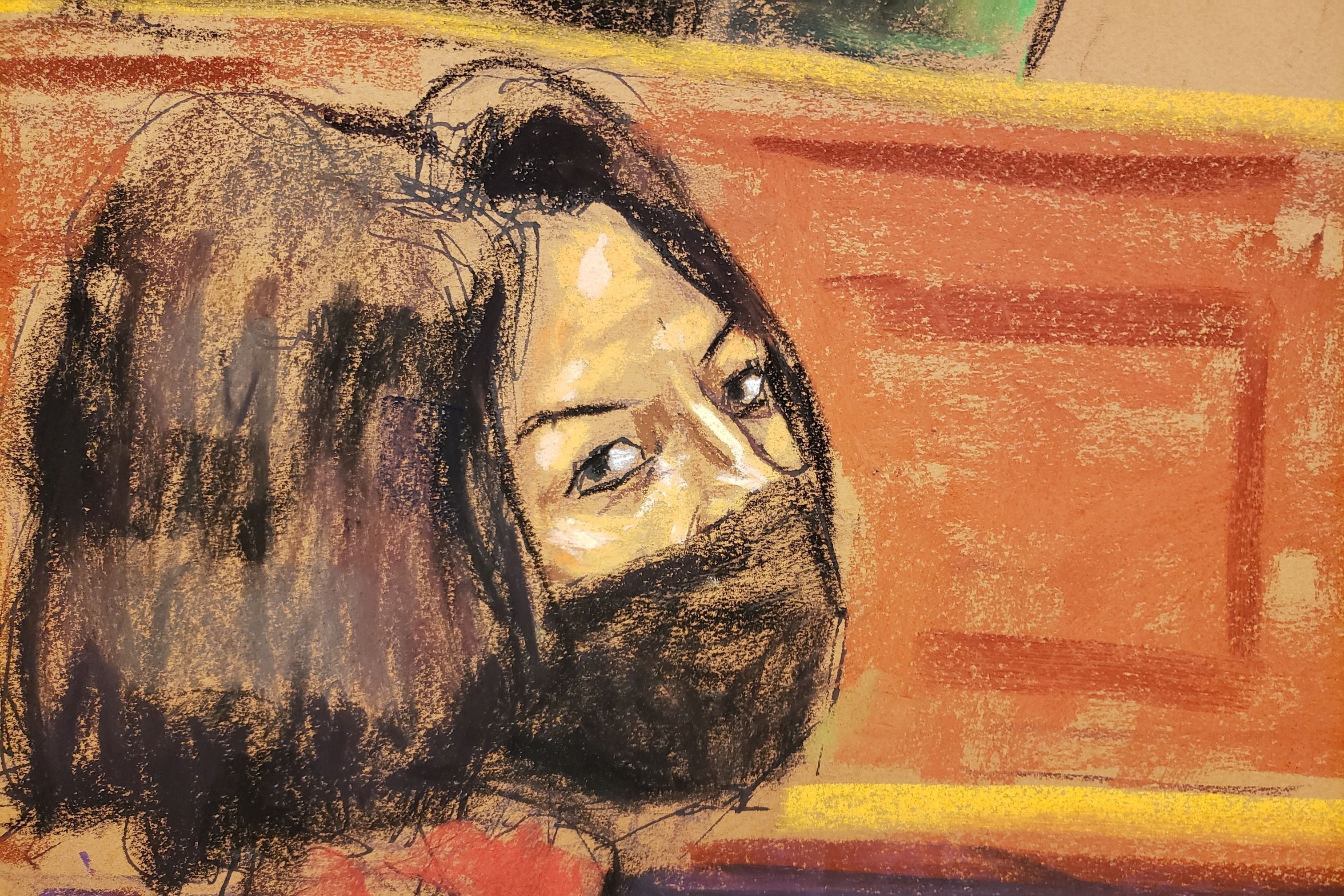

The trial of Ghislaine Maxwell, the former girlfriend and associate of the late Jeffrey Epstein, serves as a critical turning point in our ongoing reckoning with sexual abuse by foregrounding the ugly reality of female sexual predation. Maxwell stands charged with trafficking underage girls for abuse by Epstein. Witnesses say that she participated in sexual abuse incidents and helped groom many of the girls with feigned friendship, explicit conversation, nudity, and encouragement to accept money from Epstein.

Common beliefs, media depictions, and powerful gender norms point to men as the only real sexual threat. But research on female perpetrators has grown dramatically in recent years, forcing us to rethink our ideas about sexual abuse. This reconsideration is as urgent as ever: A thorough understanding of the full range of abuse is necessary to help advance the feminist lessons from the #MeToo movement and beyond.

We now know that female sexual perpetration is far more widespread than is commonly believed. My colleagues and I at UCLA Law pooled data from the 2010-2013 National Crime Victimization survey finding that a female perpetrator committed more than a third of rape and sexual assaults involving male victims and 4 percent of incidents involving female victims. Among those reporting assault by a female perpetrator, 58 percent of male victims and 41 percent of female victims reported that their female abuser hit, knocked down, or otherwise attacked the victim.

Research also unearthed a trend common among sexual assaults: Most survivors of sexual assault know their perpetrator. Female abusers, too, are typically known to the victims, who are often bewildered and wracked with self-blame in the wake of abuse. Young adults and people behind bars are especially at risk. And according to the CDC, heterosexual male victims of sexual abuse are the group mostly likely to report female abusers (71 percent of their perpetrators were female).

Women themselves actually report committing sexual abuse in surprisingly high proportions. A 2012 Census Bureau survey asked people if they had ever forced someone else to “have sex against their will.” Forty-four percent of those who said “yes” were women. And a 2013 national study of youth found that nearly half of those self-reporting rape or attempted rape by age 18-19 were female.

The research is startlingly clear: It’s time to move beyond the idea of exclusively male perpetrators.

Maxwell’s trial foregrounds a tendency specific to female abusers. While her defense team argues that she’s merely a scapegoat for Epstein, prosecutors are building a convincing case that the two operated closely together. This abuse pattern, known as co-offending, is now well documented. In fact, a 2015 analysis of federal surveys found that, compared to men, female sexual perpetrators were much more likely to have an accomplice, working with a co-offender in a third of abuse incidents. Some female co-offenders are described as “male-coerced” and are sometimes victimized themselves, while others are willing participants.

Gender stereotypes have kept us from developing a clear picture of female abusers. Today, female predation remains under-reported to authorities, in part due to victims’ fears that no one will believe them. Stereotypes about the so-called weaker sex teach that women are naïve, nurturing, and harmless, leading to widespread skepticism about female-initiated abuse. Even the female body is seen as non-threatening. “No penis, no problem,” as one scholar derisively summed up our widespread cultural indifference toward female sexual predation. When victims do report female abusers, the incidents are less likely to be charged and prosecuted. Yet people who are sexually abused by women experience the same sorts of trauma that other survivors do.

Shining a spotlight on women who commit sexual violence might seem like a thorny strategy for feminist activists who have long advanced the idea that sexual victimization is about male predation and privilege. But a better understanding of how and when women sexually violate others is not a backlash to the feminist advances in our collective understanding and treatment of rape and rape culture. Simply put: An expanded perspective on gender and sexual violence is the next critical step forward, not backward.

As the #MeToo movement revealed, well connected predators like Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, R. Kelly, and Les Moonves were allowed to operate for many years, enabled by institutions replete with sycophants both male and female. Meanwhile, victims could see that reporting abuse was more likely to hurt themselves than their perpetrators – a through-the-looking-glass reality for which #MeToo served as a vital corrective. Only #MeToo’s cultural pivot and the newfound safety in numbers has enabled victims to finally step forward..

But the #MeToo movement didn’t come out of the blue. For decades, feminist activists and scholars have pointed to power imbalances as the key driver of sexual abuse. And it’s hard to imagine a more power-soaked couple than Epstein and Maxwell, whose networks encompassed presidents, royals, and billionaires. The victimized girls, in contrast, were young, troubled, and often broke. It’s no coincidence that Epstein and Maxwell didn’t prey on girls from their own milieu.

Confronting gender stereotypes is of course another key feminist intervention. The very idea that women can be sexually manipulative, dominant, and even abusive runs counter to traditional portrayals of docile women. Disturbingly, Maxwell’s defense attorneys are milking the old stereotypes by claiming she’s merely a victim of society herself. Yes, many women are victimized. But can feminism’s emancipatory goals be realized if adult women can never be cognizant actors, able to make choices and be responsible for their own actions?

Like all complex human beings, women have the capacity for kindness and for cruelty. But Maxwell seems to have traded on stereotypes about women as always “safe.” According to victims and prosecutors, her very presence helped normalize the situation for girls who assumed that sexual abuse would never take place with a woman nearby. How wrong they were.