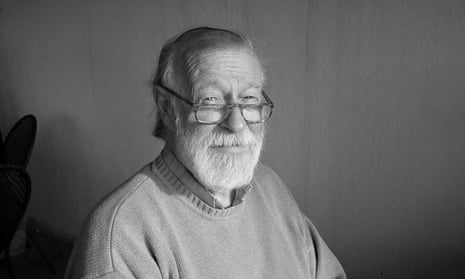

Writing from Los Angeles in 1965, the Scottish film academic Colin Young told readers of Sight & Sound magazine that Hollywood was “turning out tired material that is irrelevant to what is really going on inside Americans”. Young, who has died aged 94, became instrumental in helping to improve that situation.

In his capacity as chairman of the department of theatre arts at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA), a position he held until 1970, he facilitated an especially fecund period during which the student body included Francis Ford Coppola, Lawrence Kasdan, Barry Levinson, Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison (who formed the rock band the Doors), John Milius and Paul Schrader. “He used to collect all sorts of odd people,” said the documentary maker Terry Macartney-Filgate, who taught at UCLA. “Anyone who interested him could get in the programme.”

Young encouraged his students to look beyond their own horizons in search of inspiration. “There was a generation of Americans who didn’t find themselves in their own films, but they did, funnily enough, in European films,” he said. One unexpected consequence of the thriving American cinema he had helped to shape was that the students he went on to teach at the National Film School (known since 1982 as the National Film and Television School) in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, “couldn’t bear to think of working anywhere in the world except Hollywood”.

Young was the school’s founding director, and his students – who regarded him, according to Movie Maker magazine, as “a kind of benevolent godfather” – included Terence Davies, Bill Forsyth, Beeban Kidron, Nick Park, Julien Temple and the documentary makers Nick Broomfield, Molly Dineen and Kim Longinotto. Among later intakes were Lynne Ramsay and Joanna Hogg, whose autobiographical diptych The Souvenir (2019) and The Souvenir Part II (2021) features scenes based partly on her time at the school.

Park, whose graduation film, the stop-motion Wallace and Gromit short A Grand Day Out (1989), took seven years to make, called the NFTS “a playground to develop the craft of storytelling”. Davies recalled butting heads with Young only once, when he suggested removing an eye-catching shot from the director’s 1980 short Madonna and Child. “I hit the roof and went home full of indignation,” Davies said. “But on the way home I realised he was right … I apologised to Colin and that was a good lesson for me – if you’re seduced by how good it looks you should probably get rid of it.”

Not that there were many hard and fast rules. The school had no written curriculum or formal limit on hours and term times. This was a loose, practice-based endeavour in which, as Young put it, “everyone did a bit of everything”. He and his colleagues, he said, “change our mind all the time about the best ways to do this job. So that it’s never the same place two years running, it’s always a new school – regenerated!”

Born in Glasgow, Colin was the son of Agnes (nee Holmes Kerr) and Colin Sr, who owned three confectionery shops called the Sugar Bowl. His passion for film was rooted in the Hollywood movies he saw as a child at Saturday matinees. He was educated at Bellahouston academy, and on being called up enlisted in the Intelligence Corps. At St Andrews University, he got his master’s in philosophy and morals in 1951. Harbouring journalistic ambitions, he began working for an Aberdeen newspaper where he filled in as film reviewer, though the rigour of his critiques sat unhappily with advertisers, and his tenure in the role was brief. He travelled to California where he worked as a gardener to save the money necessary to enrol at UCLA. By his second year, he was teaching there to help cover his fees.

After gaining his theatre arts degree there, Young briefly joined the writing department at MGM as a “technical adviser”, and was impressed by the unfussy attitude of his colleagues. “These guys just did things by the seat of their pants,” he said. “I was amazed how quick they were to spot a weakness in the story without ever wishing to change the story, but simply to strengthen the storytelling.”

In 1958, he became Los Angeles editor of Film Quarterly magazine, which published some of the first English translations of writing by the auteurist critic André Bazin; Young was also its London editor for 21 years from 1970. He was invited back to UCLA to teach, and given the department of theatre arts to run in 1965.

He brought in esteemed guest tutors including Jean Renoir, and helped create the university’s ethnographic film programme as what was called an ethno-communications programmme, which provided opportunities for film-makers of colour; these included Charles Burnett, director of Killer of Sheep (1978) and To Sleep with Anger (1990). Young argued for the importance of film school over learning on the job. Here, he said, students are given “the chance to practise with film and get it wrong, again and again, until they eventually get it right”.

He returned to Britain in 1970 after being invited to apply to found the country’s first national film school, a move by the government to revitalise the British film industry. He was looking, he said, for candidates who were “emotionally mature and intellectually lively – and have a feel for putting images together meaningfully and interestingly. In short, they must be publicly-spirited egomaniacs who are terribly talented.” The school opened its doors in September 1971. Initial students were given the task of making a documentary on some aspect of Beaconsfield life; Broomfield focused on a local MP, while others set up a sentry post on the edge of the town, stopping people to ask them for passports and then filming the results.

He left the school in 1992 and established in Paris the Ateliers du Cinéma Européen, a training and development centre for European producers. He was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1987 and a Bafta fellow in 1993. Writing in 2004 in the Journal of British Cinema and Television, Duncan Petrie argued that Young’s “contribution to the development and maintenance of a serious film culture ... makes him as important a figure as his fellow Scot, John Grierson”.

The seeds of Young’s philosophy were there from the start. In 1954, he published an article about film societies in which he advocated the migration from viewer to practitioner, insisting that any climate “in which film watchers will be encouraged to become film-makers, even at an amateur, exploratory level … is a development in the right direction. There comes a time when a man cannot listen to another word about film criticism. He simply has to forget talking, and go out and shoot some film.”

In 1987 he married Conny Templeman. She survives him along with their children, Keir and Zoe, and two sons, Colin and Cairn, from his first marriage, to Kristin Ohman, which ended in divorce in 1985.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion