In 1971, Shirley McGreal, who has died aged 87, encountered crates of infant monkeys awaiting export from the cargo area of Bangkok airport. The sight of them piled on top of each other in inhumane conditions, gazing at her with doleful eyes, led her to start reading everything she could about primates and to begin contacting primatologists around the globe. Two years later she set up the International Primate Protection League (IPPL) with the support of Ardith Eudey, a researcher into the stump-tailed macaques that Shirley had seen at the airport.

Shirley and Ardith set about investigating the enormous traffic in macaques for use in biomedical research. One of their first initiatives, in 1975, dubbed “Project Bangkok”, involved a team of Thai students monitoring all wildlife exports from Bangkok airport over 10 weeks. They revealed staggering volumes of some 100,000 mammals, birds and reptiles, many in appalling conditions, in violation of international standards. Thailand banned the export of all primates shortly afterwards.

Another success followed in 1977 when IPPL revealed that macaques being exported to the US from India were being used in chemical warfare experiments. As a result, India enacted a similar blanket ban on primate exports that is still upheld to this day. A further export ban in Bangladesh, where interest from the US had shifted, followed in 1979, and Malaysia in 1984.

Ardith’s studies in Thailand were for her doctorate at the University of California. In 1974 she discovered that gibbons were being illegally smuggled out of an American army medical research facility in Bangkok to a research lab at her own university in the US. IPPL reported the case to the US Fish and Wildlife Service but was eventually told it had been dropped, not for lack of evidence, but because it was “too sensitive”. However, the following year, due to the publicity surrounding the IPPL investigation and an ensuing report by the US National Academy of Science, the lab lost its funding and the remaining gibbons were sent to other facilities.

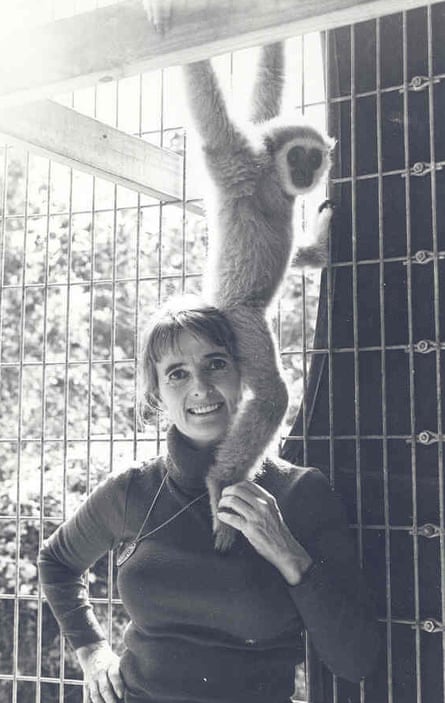

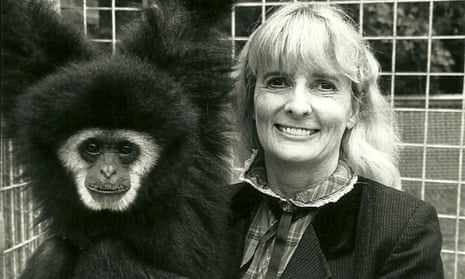

One “metabolically abnormal” gibbon could not be rehomed. Shirley, who was now living in South Carolina in the US, and had already rescued one gibbon, stepped in, beginning her journey towards running what is now a vast gibbon sanctuary on 47 acres of land.

Born to Kate (nee Pearson) and Allan Pollitt, a bank manager, in Mobberley, Cheshire, Shirley studied French and Latin at Royal Holloway, University of London, graduating in 1955. Her identical twin sister, Jean, went to the London School of Economics, and it was as young graduates that the twins first became involved in activism, taking part in demonstrations for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and the Committee of 100 anti-war group. Though they lived in different countries in later life (Jean settled in Canada), they remained extremely close, often speaking several times a day, with Jean serving on the board of directors at IPPL until her death in 2009.

Shirley studied French at postgraduate level at the University of Illinois, where she met John McGreal, an engineer, whom she married in 1960. They moved to the University of Cincinnati for further study, and then to India, where John worked at the United Nations and Shirley on doctoral research in education, until their move to Thailand for John’s work, and her fateful airport encounter.

Shirley was a firm believer in grassroots conservation; she had a long legacy of seeking out and nurturing frontline conservationists around the globe. As well as organising and attending primate welfare and conservation conferences, Shirley spent her days investigating cases of illegal trafficking, courageous in pursuit despite the intimidation and death threats that could ensue. Through her extensive network of contacts, she would receive tip-offs that she would then investigate, either through formal means, or undercover.

She would often pursue a number of routes to get what she wanted. For instance, in 1975, she uncovered the “Singapore connection”, whereby primates were being smuggled into Singapore and exported from there under falsified permits. After contacting first the Singapore government, then the governments of the countries where the primates were being captured, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, to no avail, she wrote an exposé for the Bangkok Post. This was picked up by the Reuters news agency, went global and embarrassed the Singapore government into action.

I met Shirley in 2008 when I took over the running of IPPL’s UK branch from Cyril Rosen, and I continued to work with her over the next decade as an IPPL board member and chair. Though then in her 70s, Shirley was still a passionate and hardworking activist. She spoke fluent French, and had wide-ranging interests, from politics and literature to opera and ballet. She was also warm and quick-witted with a keen sense of humour.

Of the many awards she received, she was proudest of one from the Interpol Wildlife Crime Group and the Dutch Police League in 1994 for exposing an international ring of primate smugglers.

During a related case in 1993, which involved the smuggling of six infant orangutans – four of which died during transit – Shirley was outraged to learn that one of the principal players had been given a misdemeanour plea bargain. She galvanised her network to flood the judge with more than 1,000 letters of protest. The judge insisted on a felony plea, including a jail sentence, and disqualified the trafficker from further international dealing.

One of the protest letters was from The Duke of Edinburgh, with whom Shirley carried out a long correspondence from their meeting at a conference in 1981 until his death earlier this year. When Shirley was made OBE in 2008, she also enjoyed a private audience with the duke.

In a letter written in 2015, he wrote: “I am glad to know that IPPL continues to flourish and keeps up the good work of pursuing the crooks, rewarding the righteous and caring for 36 gibbons!”

Shirley is survived by John and by two nieces, Yvonne and Michelle.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion