- India

- International

How Mumbai’s CSMVS became a repository of memories and culture, through wars, plague and pandemic

In its centenary year, a look at how the iconic Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya tells stories of our shared humanity

The CSMVS building at Kala Ghoda (Source: CSMVS Collection)

The CSMVS building at Kala Ghoda (Source: CSMVS Collection)After more than a decade’s wait, a museum was set to be inaugurated in 1921 as a memorial to the Prince of Wales. Built in the Indo-Saracenic style, the memorial would have art, archaeology and science sections, and represent the Bombay Presidency and Sind. It would also encompass the “Oriental region”, including Tibet, Yunnan, Syria and Iran.

However, when Edward VIII, the Prince of Wales, landed in Bombay in November 1921, he was greeted by non-cooperationists and riots that lasted three days. To the great disappointment of the museum trustees, the royal inauguration did not materialise. Then on January 10, 1922, the memorial was inaugurated by the collector of Bombay, JP Brander, and the wife of the governor, Lady Lloyd. With no prince in attendance, the memorial fulfilled its destiny as the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India.

The museum, renamed Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Kala Ghodha, is currently home to 70,000 objects, 26 galleries, and exhibition spaces that match international standards — all of which are managed by a staff of 220. The much sought-after destination attracted a footfall of 10 lakh annually pre-pandemic — tourists, picnickers, school students, art historians, numismaticians and zoologists. It celebrates its centenary this year.

The Sword of Damocles (1904) by Antoine Dubost, part of the Tata Collection at CSMVS (Source: CSMVS Collection)

The Sword of Damocles (1904) by Antoine Dubost, part of the Tata Collection at CSMVS (Source: CSMVS Collection)

In the pandemic, CSMVS was shut for 16 months, and has survived solely on patronage. It’s a strong reminder of its tumultuous origins. As delayed as its opening was in 1922, the building had been operational since it was completed in 1914. Forgoing its intended purpose, the building first operated as Lady Hardinge Hospital for Indian soldiers in World War I. Then again, during the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-20. In World War II, the main building of the otherwise functional museum was closed for five years to allow the Red Cross to function.

“The history of CSMVS is the history of Mumbai,” says Sabyasachi Mukherjee, its 57-year-old director, who has lived and worked on the campus for the last 15 years. He says, “It was largely people who contributed to the making of the museum. It’s a history that fortunately continues in today’s Mumbai.”

Mukherjee often describes CSMVS as “by the people, for the people”. To start with, the museum opened with a bequest. Ratanji Tata, son of industrialist Jamsetji Tata, had a significant art collection with noteworthy objects, such as The Sword of Damocles (1804) painting by Antoine Dubost, Mughal emperor Akbar’s armour and shield, and folios from an illustrated manuscript of Nala-Damayanti from 1699. TR Doongaji, a trustee of the museum and former managing director of Tata Services Ltd, writes in the Tata Central Archives newsletter in 2021 that of the 5,700 objects at the time of the museum’s opening, over 70 per cent came from this bequest.

A decade later, another bequest followed — Dorabji Tata’s, Ratanji’s elder brother. It had rare pieces from the Ming dynasty, European paintings, and personal memorabilia. The bequests together form the Tata Collection, which celebrates its centenary alongside the museum.

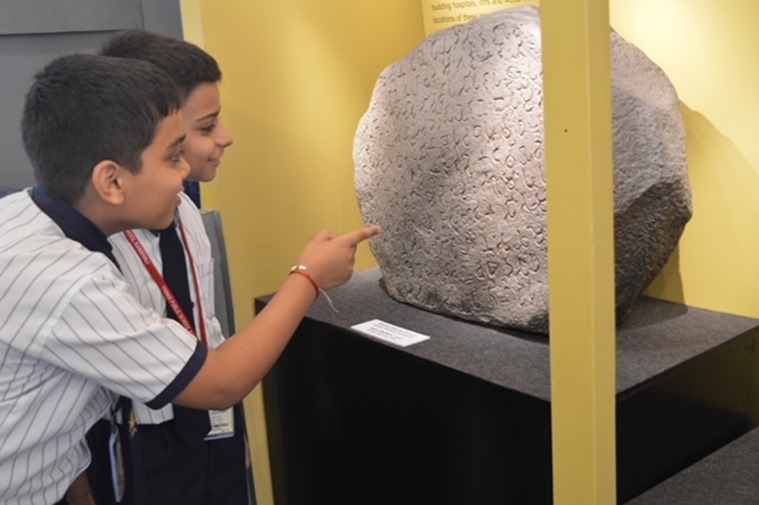

Children look at the Ashokan Edict No 9 from about 250 BC, discovered in Nala Sopara, Thane. It is one of the rare objects in the CSMVS collection (Source: CSMVS Collection)

Children look at the Ashokan Edict No 9 from about 250 BC, discovered in Nala Sopara, Thane. It is one of the rare objects in the CSMVS collection (Source: CSMVS Collection)

The CSMVS, often mistaken to be a government institution, is in fact an autonomous body unaided by the government. It receives an annual grant from the municipal corporation — a sum of Rs 25,000 since 1922 that was increased to Rs 50,000 in 1970, which has stayed the same since. There was one instance of the Ministry of Culture sanctioning a modernisation grant of Rs 20.3 crore, which was used to create an auditorium, the signage, a conservation centre, a cafeteria and a travelling “museum-on-wheels”, among other improvements.

“We have to move with the times, otherwise youngsters think it’s a dead space. In some parts of India, museums are referred to as ajayab ghar, a place for curios, but people have to understand that this is their own culture preserved here, their guiding force,” says Manisha Nene, director of galleries and general administration at CSMVS.

She cites the instance of CSMVS’s Himalayan Art Gallery, which had great examples of the region’s culture, but once saw few footfalls. Visitors had curiosity but lacked context. To solve the problem, the team spent time in Ladakh and nearby regions, and introduced prayer wheels, audio-visual guides and even a gompa in the gallery. Footfalls rose gradually.

CSMVS was the first Indian museum to introduce audio guides, an idea devised by Kalpana Desai, who became its director in 1996. She recalls, “The museum was centred only around scholars, researchers and curators. We tried to make it a more public-oriented institution.” Now based out of Vadodara, Desai says, much of her time as the director was spent in improving the museum’s infrastructure rather than its collections. The museum’s extension wing used to be “a dingy, jail-like area with walls so weak that they could fall if you blew on them”, Desai recalls. Out of these shambles, a three-storey extension wing was created by architect Rahul Mehrotra and his team in 2002 and funding came from business house Premchand Roychand & Sons.

Desai also saw the museum forced to shed its old colonial name and take on a new one in 1995, under the Shiv Sena government, which was interested in projecting a Maratha association. This was soon after Bombay was changed to Mumbai. Incidentally, CSMVS’s collection has one of the four known portraits of Maratha king Shivaji, made around 1675 in Bijapur.

A painting of the military procession of the Golconda court of Abdullah Qutb Shah from the mid-17th century, part of the CSMVS collection (Source: CSMVS Collection)

A painting of the military procession of the Golconda court of Abdullah Qutb Shah from the mid-17th century, part of the CSMVS collection (Source: CSMVS Collection)

When Mukherjee succeeded as director in 2007, his attention turned to the museum collections and collaborations with peers in India and abroad. In 2013, he brought the Cyrus Cylinder from the British Museum for an exhibition of ancient Persian artefacts. The cylinder, from 6th century BC, was displayed alongside a rare Ashokan edict from about 250 BC, discovered in Thane and part of the CSMVS collection. For Mukherjee, this was one of his favourite museum moments—to see the two artefacts, from different regions, conveying ethical codes of behaviour.

“Museums are a symbol of culture and a coming together of different communities. Such experiences motivate people to become part of cultural conversations and help them to respect similarities and differences,” Mukherjee says. CSMVS has shaken off the unfortunate connotations that museums have in India — dusty, poorly lit, spaces for broken objects — and is an institution that has the capacity to pull together different eras and regions. The museum has hosted an eclectic collection from home and the world comfortably under one roof – be it the late Bollywood actor Shammi Kapoor’s memorabilia, a 3000-year-old Egyptian mummy, a 6th century Shiva sculpture discovered in Mumbai, or a Rembrandt and a Rubens.

For the centenary, the museum staff has prepared a mega line-up of exhibitions, lectures, publications and plans for the museum. CSMVS unrolled its centenary celebrations last week with a virtual event, which included an exhibition of its latest acquisition, Thanjavur paintings from the collection of the late Delhi architect Kuldip Singh. Other plans include a 300-seater semi-underground auditorium; a new gallery on the ancient world, in collaboration with the British Museum, Berlin Museum and Mexico Museum, supported by the Getty Foundation; and another gallery on sacred art. CSMVS is also set to strengthen its bond with Mumbai, with the development of a digital archive of the city’s maps and photographs, and a gallery specially dedicated to the city.

Born in one crisis and turning 100 in another, this veteran museum has survived to tell its story, and ours.

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05