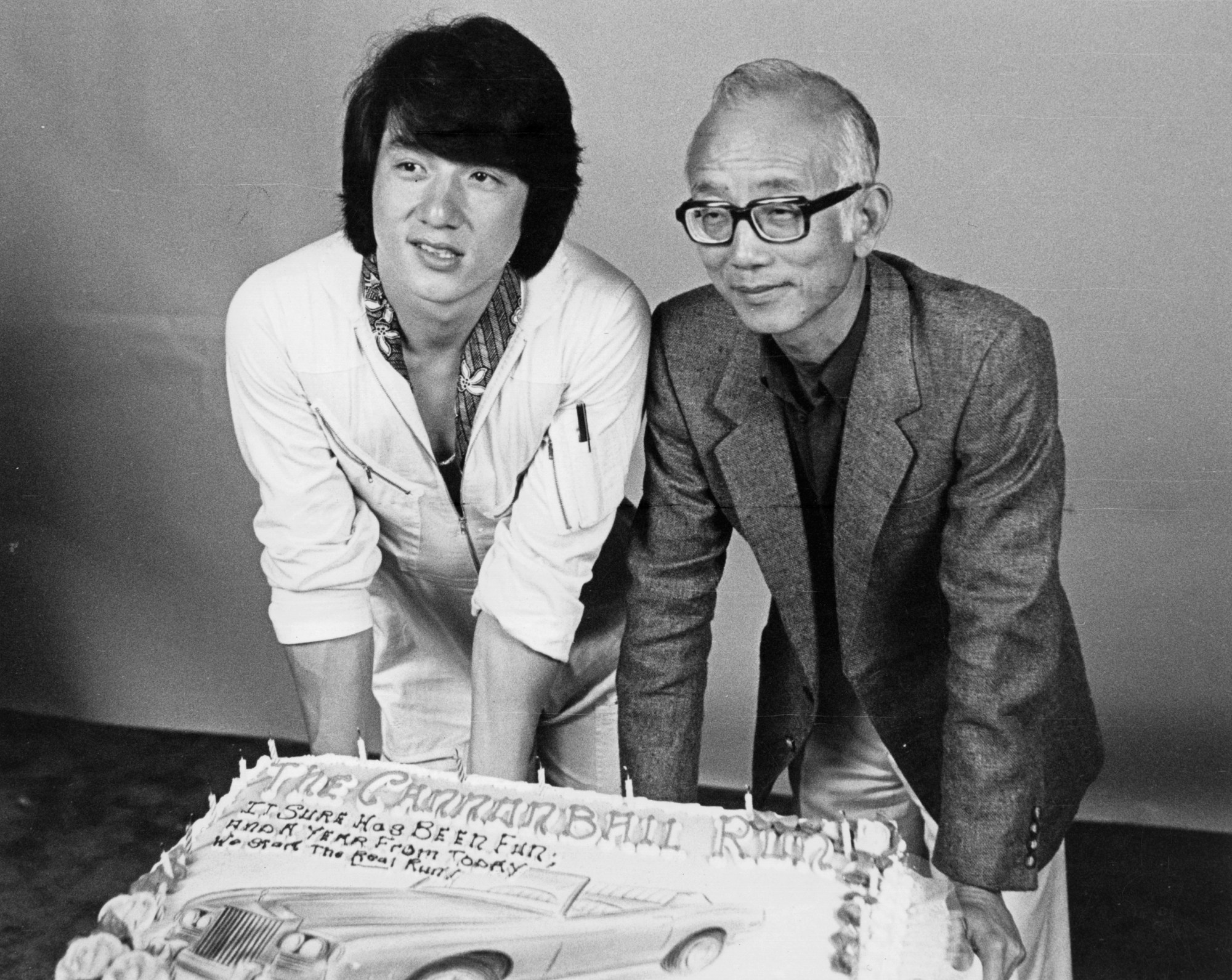

Jackie Chan in America: how The Cannonball Run and The Big Brawl, Hong Kong martial arts star’s early Hollywood movies, persuaded him to turn focus back to home

- Battle Creek Brawl (also called The Big Brawl) has martial arts scenes that are neatly choreographed and showcase Chan’s skills, but it wasn’t a box office hit

- Chan had a small role in The Cannonball Run, but the focus was on its star, Burt Reynolds. ‘I knew If I stayed in the US, my career would be finished,’ he said

Although it’s almost lost to film history, Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest studios was very active in international film production during the 1970s.

“Shaw Brothers offered me more money, but Golden Harvest told me they would make me a star in America,” Chan told this writer in an interview.

“When the price that Shaw [Brothers] were offering went higher than [Golden] Harvest could afford, Raymond Chow told me, ‘Look, we can’t give you any more money, but I promise to make you an international star.’ I mentioned this to Shaw Bros, but they didn’t really say anything about America. So I signed with Golden Harvest – and I held them to that promise.”

Maggie Cheung had ‘no interest’ in martial arts films – but did them anyway

Chan’s first film for Golden Harvest was the 1980 hit The Young Master, which he directed – being allowed to direct his own local films was another condition of Chan’s contract.

Battle Creek Brawl (aka The Big Brawl) followed that year. The story takes place in the US in the 1920s, where Chan competes in a rough-and-tumble fight competition while trying to meet the demands of various gangsters.

Chan is the hero of the story, and has a love affair with a Caucasian, even kissing her on screen – something that was still taboo in US cinema in the 1970s.

“Forget about the simple plot and the implausibility and overall corn of it all – just sit back, munch on a bag of sweet popcorn and enjoy the kung fu capers of the appealingly boyish Jackie Chan,” wrote local critic Mel Tobias in a review published in the Post book Memoirs of an Asian Filmgoer.

“Jackie displays his comedic brand of kung fu with breathtaking speed as he undergoes training with his uncle … the two go through snappy funny routines that frequently draw howls from the audience,” wrote Tobias, noting that the film would go down well with Western audiences “easily impressed with oriental oddities and exotica”.

Unfortunately, US audiences were not impressed, and Battle Creek Brawl failed at the box office. “I don’t think it is a bad film. I remember going to see it in a theatre in the US, and the audience seemed to like it,” Chan told me.

“The people who went to see it were satisfied, but a lot of people just didn’t go and see it. I had a big African-American following in the US at that time, but most people didn’t know who I was, so they stayed away. It didn’t make me an international star, and to make it worse, the film didn’t do as well as The Young Master in Asia, either,” he said.

With hindsight Chan said he understood why the film underperformed. “Apart from American audiences not knowing who I was, they also didn’t like the kind of fighting I was doing. They did not think my punch was hard enough – I wasn’t as powerful as Bruce Lee, knocking someone down with one punch, which is what they liked.

“My kind of action is actually more sophisticated, but they just didn’t accept it. Because of this, there was no interest from the media, and the film didn’t get much coverage,” he said.

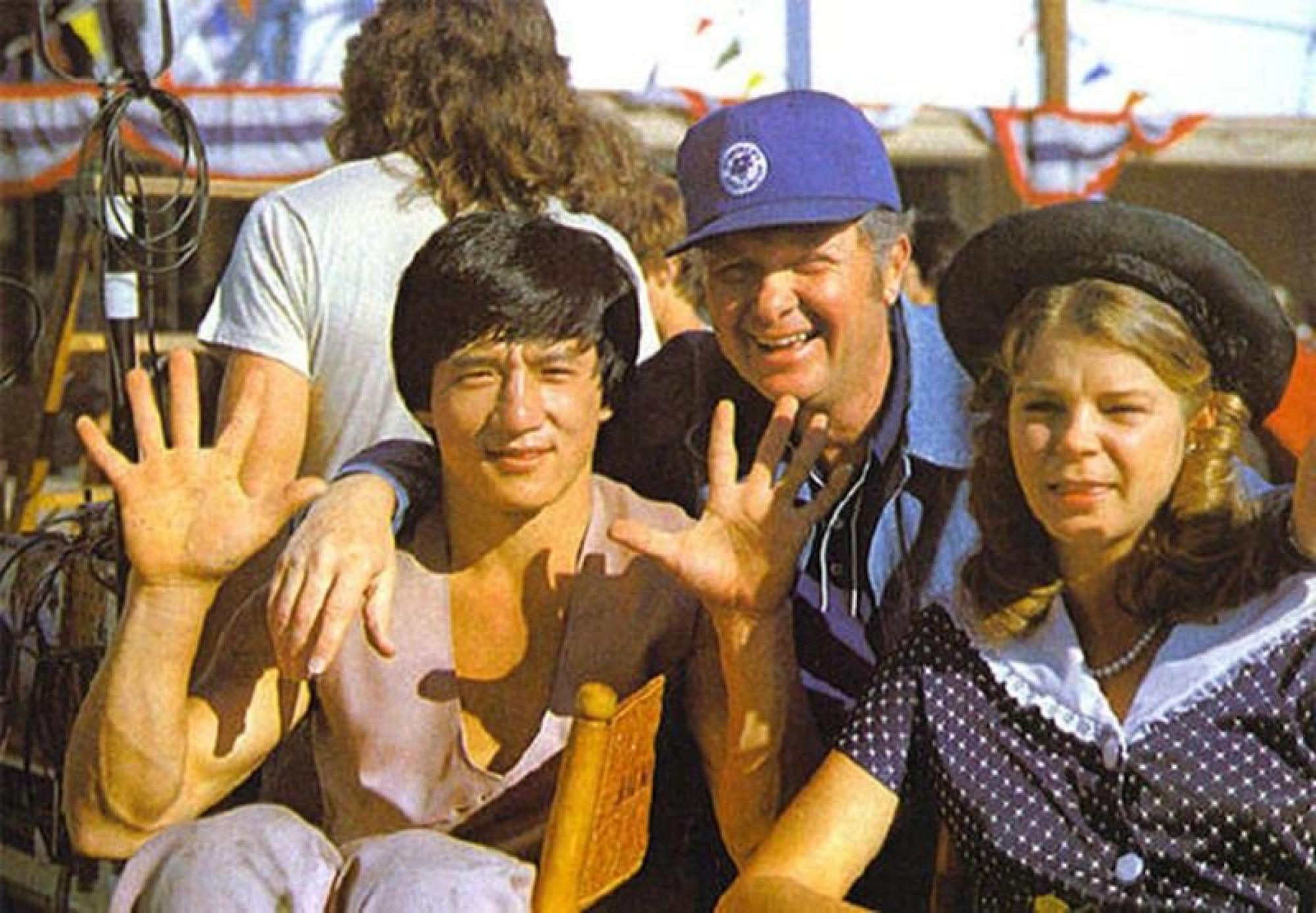

The failure of Battle Creek Brawl led to a smaller appearance in The Cannonball Run (1981), an appalling madcap comedy which focused on its star, Burt Reynolds. Chan was not downgraded by Hollywood – it was his decision to play a smaller role.

“After The Big Brawl failed, we sat down with American producers and said, ‘Shall we try a TV series first to get me known, and then do a movie? They said that was a bad idea, because if you get known on TV, you are a TV star, and your movie career is over.

Jackie Chan’s 10 best films ranked, from Police Story to The Foreigner

“Someone suggested that I do a movie as a guest star to get attention, so we did Cannonball. But everyone went to see Burt Reynolds, and no one noticed me. Worse, people came to see me in it in Asia, and I wasn’t in it much. My popularity in Asia began to slip as a result.”

“I knew If I stayed in the US, my career would be finished. There were a lot of big stars in America, and if I stayed, I would be the smallest of the stars – and nobody seemed to like me much anyway. So I said, ‘That’s it, I’m coming home to Hong Kong to make my own films.’”

Chan did return to the US for a small part in The Cannonball Run sequel, and made one more attempt to crack the US market with the universally reviled The Protector in 1985.

The violent cop story, set in Hong Kong and New York, features gunplay and brutal violence, and the American version does not highlight Chan’s abilities – “I seemed like just another action star,” he said. Chan reportedly tried to choreograph his own martial arts scenes, but was refused by director James Glickenhaus.

The Hong Kong cut Chan edited himself, which features new combat footage and a whole extra plot line featuring Sally Yeh, is better, but that did not help his success in the US. After The Protector, Chan kept his focus on Asia until 1995’s big breakthrough with Rumble in the Bronx.