Quick to learn and eager to please, the rare Spanish colonial horses remain untouched by interbreeding. But their population is on the decline.

Heidi Collings grew up with horses, but she was blown away by her first encounter with the Wilbur-Cruce, the only pure breed of rancher horse descended from Spanish colonial times. In 1995, a friend brought an untrained colt to her Arizona ranch. Collings threw a saddle on him, his first. An hour later, he was moving cattle in the pens. He pushed them about as though he had done so his entire life. No horse she had ever ridden before had done that.

“He handled everything like he had grown up with it,” Collings recalls. “He was very steady, with a real work ethic. He did whatever we asked him.”

She acquired her own Wilbur-Cruces, and the cowboys working for her found the horses had amazing endurance. Quarter Horses, the most popular breed on ranches, need to rest following a hard day. Not Wilbur-Cruces. They are ready for action the next morning.

“These horses spoil you,” says Collings. “You get hold of these and you don’t want to deal with anything else.”

Other owners echo her sentiments. The Wilbur-Cruces are quick learners and eager to please. They are loyal to their human partners—the closest thing to working dogs. They don’t alarm livestock and react calmly to ropes swung over them. They’re reliable and always on call. Although on the smaller side—measuring on average 14 hands, or 56 inches, high—they are extremely hardy.

Photo courtesy of Robin Collins.

“They’re perfect for farms and working cattle,” says Robin Collins, who owns around 40 Wilbur-Cruces near Fresno, California.

But there’s a hitch. The Wilbur-Cruces are nearly extinct. At most, 160 remain, all in the US, despite there being a dedicated preservation attempt by private individuals. That’s because so few people know about the animals and resources are scarce. Horses are costly to maintain, and breeders need money, as well as eager buyers, to bring more into the world.

A handful of other strains of Spanish colonial horses exist in North America, such as the Choctaw and Baca. But unlike mustangs, which are feral horses that are often mixed with other types, the Wilbur-Cruces have the genetics of original Iberian horses, untouched by interbreeding.

[RELATED: 20 Farm Horses From the Past]

The Wilbur-Cruces descend from a herd brought from Spain to Mexico in 1681 by Padre Kino, a missionary rancher. In 1885, an American named Ruben Wilbur brought 25 mares and stallions to his rugged desert ranch in Arizona where their descendants remained isolated for another century. When the ranch was sold in 1990, 77 horses were donated to what is now known as the Livestock Conservancy, which seeks to save endangered heritage breeds. Collins took many of the equines and other enthusiasts joined her effort to preserve the bloodline. But numbers have fallen as funding dried up and breeders aged out.

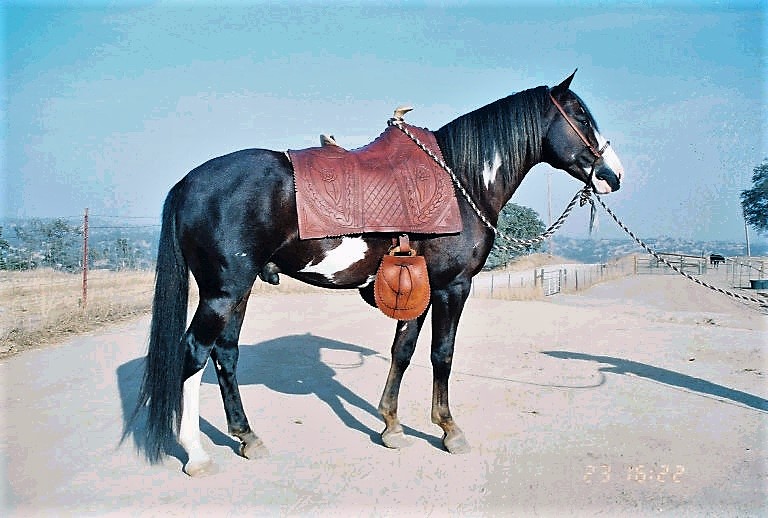

A Wilbur-Cruce horse gets ready to sort some cows. Photo courtesy of Stephen Turcotte.

That’s a shame, says Phillip Sponenberg, a genetics professor from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine who has studied Wilbur-Cruce horses for 25 years.

He says the varied DNA that created such a fine working horse could prove useful for future generations. They can do a range of activities, unlike modern lines that are bred for one purpose, such as racing or jumping. Wilbur-Cruces were always used for plowing, draft, livestock and transport.

Sponenberg also stresses the cultural heritage of the American West, where Spanish breeds predominated until the 1800s. “We save historic buildings, yet these are a living record of human endeavor,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Robin Collins.

Sandra Esposito believes more people would own the horses if they saw them in action. She uses her Wilbur-Cruces to go camping and pack supplies as a forest volunteer in California’s Sierra mountains. She finds them to be the most grounded and intelligent horses. One even figured out how to trot around barrels and poles by watching others. “They’ll see a problem and think about it and say, ‘We’ve got this.’”

They are also remarkably agile, says Rear Admiral Steve Turcotte. A Wilbur-Cruce gelding is the go-to rope horse on his craggy cattle farm in Arizona. The steed goes shoeless through the Aravaipa canyons. “These horses scramble up rocks and cliffs that I wouldn’t hike on,” he says. “My farrier says they’ve got the best feet he’s ever seen.”

[RELATED: Harness the Power of Draft Horses]

The downside? Wilbur-Cruce horses get bored without a task at hand. They don’t like circling in a ring without a purpose. And their affection can get in the way. Owners say it’s hard to clean up manure because they’re always at your elbow, asking for a rub.

Photo courtesy of Stephen Turcotte.

Still, conservationists persevere, working to get the word out. The Spanish Barb Horse Association does education about this rare strain and others. It advertises breeders and horses for sale. Turcotte offers his black stallion, Amigo, to mate for free. But business is largely word of mouth, and few Wilbur-Cruce foals are born each year.

At 76, Collins worries about what will happen when she can no longer care for her Rancho del Sueno sanctuary. The pandemic has further complicated that. Vet bills cost $35,000 a year, the price of feed has doubled and she can’t do educational programs like before.

“These horses were instrumental in the development of humanity,” she says. “We need to keep them alive.”

The Packard Foundation, Former Mrs. Bezos, and former Mrs. Gates need to step up. His is just the kind of historic and natural preservation that they support.

Interesting! I am not a horse person, but why are the vet bills so expensive. Moving to land in Costa Rica and wanting to learn more.

You have peeked my curiosity and I am interested in getting more information. What size are they? How would one get one or two of them? If I were to consider breeding them to help in their existence, how would I go about that? I have a farm in the middle of Woodford County, Kentucky (center of the Bluegrass and thoroughbred capital) and it would be a good home for them I would think. Please connect with me via contact info below. My phone no. is 859-207-8683. Best regards, Craig

I would love to acquire a stallion and two mares. Where would I find these horses for sale? I’ve not been able to find a breeder with horses in an online search.

Tell us more. I am a Lippit Morgan man but find this fascinating.