- India

- International

Long before Sarojini Nagar, there was Vinay Nagar, providing accommodation to Delhi’s ‘polite’ clerical staff

🔴 In the pre-liberalised era of the mid-1950s, the government remained the biggest employer of educated and aspirational young men and women, and Delhi welcomed a majority of them. Following the departure of the British, the scope and responsibility of the government had expanded greatly, and there was a sharp increase in government jobs.

Vinay Nagar was among 10 such areas planned by

the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) in the 1950s to house new government employees. (Adrija Roychowdhury)

Vinay Nagar was among 10 such areas planned by

the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) in the 1950s to house new government employees. (Adrija Roychowdhury)Writer Khushwant Singh, in his classic on Delhi, had very aptly described the Capital as a “grangerous accretion of noisy bazaars and mean-looking hovels growing around a few tumble-down forts and mosques along a dead river”. Indeed to the newcomer, Delhi would come across as an overwhelming metropolis, its swanky residential neighbourhoods just as daunting as the narrow, overcrowded ones. Yet, it is also true that this is the city of aspirations, thronged by millions each year in hope of education, career, or just a better life. From the exasperated refugee escaping the bloodshed of Partition to the dreamy-eyed IAS aspirant, Delhi as the capital of an independent India was built for the migrant and by the migrant.

The Delhi rewind series is an attempt to trace the history of the city from the moment it transformed from the capital of British India to that of an Independent India. As the capital, Delhi had to be built ambitiously and appropriately for the international gaze while being reimagined to accommodate the large number of migrants from across the country. Through little nuggets of history, this series will put together the story of Delhi post 1947.

To the newcomer, Sarojini Nagar is synonymous with flea markets. For Paritosh Bandopadhyay (82), this was one of his first homes in the national capital. It was called Vinay Nagar at that time, named after the virtue of ‘politeness’ (vinay) expected from clerical staff residing in this neighbourhood.

Bandopadhyay, then 25, had recently bagged a coveted job in the Press Information Bureau of the Information and Broadcasting Department, and moved to Delhi from Calcutta.

“The government had painted a rosy picture of an easy climb up the bureaucratic ladder and benefits such as free accommodation. I was quite attracted to the idea of a central government job and managed to clear the examination,” he said.

In the pre-liberalised era of the mid-1950s, the government remained the biggest employer of educated and aspirational young men and women, and Delhi welcomed a majority of them. Following the departure of the British, the scope and responsibility of the government had expanded greatly, and there was a sharp increase in government jobs.

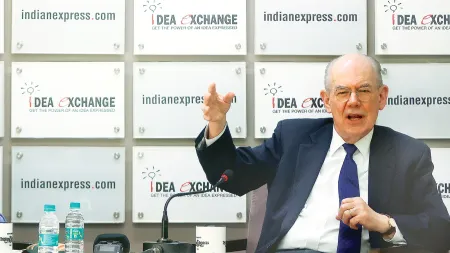

“The nature of the state became very different after independence. Under the colonial state, the government had very limited functions. It only policed, collected revenue and embarked on certain construction projects,” explained historian Swapna Liddle. “The post-Independence state played a much more active role in agriculture, industry and a lot more.”

The interim general plan for Greater Delhi, produced by the Town Planning Organisation in 1956, noted that approximately 40% of urban Delhi was dependent on government jobs. Consequently, earmarking and developing neighbourhoods to house employees of the central government was a most pressing requirement.

Vinay Nagar was among 10 such areas planned by the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) in the 1950s to house new government employees. Shan Nagar, Kaka Nagar, Laxmi Bai Nagar, Man Nagar, Moti Bagh, Sewa Nagar, Bharti Nagar and Lodhi Colony were other such government colonies.

“Each of these areas was within five to six kilometres of the Central Secretariat,” explained A K Jain, urban planner and former commissioner of planning with the DDA. “The plan was to accommodate government employees in the south of Lutyens’ Delhi and private colonies and commercial establishments would be in the west.”

In her 2018 book, ‘Negotiating Cultures: Delhi’s Architecture and Planning from 1912 to 1962’, Professor of Architectural Design Pilar Maria Guerrieri wrote that each of these neighbourhoods was envisioned with a specific architectural style. Individual tastes of the residents played no role and were subordinated to the overall vision of the CPWD. These were low-density settlements with two storeyed houses or groups of houses. Each house has a private park at the rear, and a common garden in the front is shared by a cluster of buildings.

“They are clean, simple, and semi-modern with functional architecture,” wrote Guerrieri.

Based on rank and role of the officer, the houses range from type one to type eight. The type one consists of a single bedroom, kitchen, and bathroom along a corridor, while type eight is a bungalow with three bedrooms, two bathrooms, living rooms and a kitchen.

Despite the many efforts made by the government to house its new employees, very few in fact managed to get free accommodation. Bandopadhyay said that one had to wait for a long time before being allotted accommodation. The allotment would depend on the rank of the officer and availability of housing. For the 15 years that he worked in government service, Bandopadhyay was in fact never allotted housing, even though he lived in the government colonies.

His first accommodation in East Vinay Nagar was a rented room in one of the quarters. “Officers would often rent out one room in their allotted quarter to someone who had not received housing,” he said. “It was a small 12×12 feet room, sufficient for a single person. In one corner, I had a kerosene stove for cooking.”

After moving out of Vinay Nagar, he moved to Lodhi Colony, another neighbourhood built for government housing. There he stayed at a chummery, which were quarters built by the British to house soldiers during the Second World War. After the war ended, they were made available to unmarried male government officers.

“It was like a mess. Each room was allotted to a single officer, who would then be joined by a few of his friends. In my room for instance, four or five of us lived together,” said Bandopadhyay.

Despite the congested living conditions in these neighbourhoods, an atmosphere of camaraderie and fun had developed due to the presence of a large number of young people, most of whom were new to the city. Bandopadhyay recollected the number of literary clubs, drama clubs and the like that had been formed by the officers for recreation.

He also has fond memories of striking up a close bond with another Bengali boy who had grabbed a job in the education ministry. “He was having a particularly hard time managing food in Delhi since he did not know how to cook. On his request, we started preparing our meals together. He would grind the spices and I would do the cooking. In the process, we became very good friends,” said Bandopadhyay.

Apart from housing, the growth prospects in the government also came as a disappointment to many like Bandopadhyay. “These were the years immediately following Independence and rules related to the government jobs were not framed clearly. Consequently, we had to wait for many years unnecessarily to get a promotion,” he said. “But we hoped for something good to happen since avenues were very limited.”

Keeping the challenges aside though, Delhi, with its broad roads lined up with blooming amaltas and large tamarind trees, had won Bandopadhyay’s heart. One of the many reasons he had aspired to move to the city was the prospect of meeting different people from across the subcontinent.

The government colonies of Delhi were among the earliest spaces where people from all over resided together, breaking down caste, class, and regional boundaries. The men shared food and drinks, and travelled to work together. The children played together and the wives found friends and confidantes in these humble, almost boring looking quarters.

Today, large parts of these neighbourhoods are being torn down for redevelopment. “Most of the houses are about 60-70 years old and have become dilapidated. So, the CPWD and NBCC started redeveloping them from 2008 onwards,” said Jain.

With the city having changed significantly in the last seven decades, these colonies are now being redeveloped for a denser population and larger commercial activities.

Buzzing Now

Apr 16: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05