- India

- International

India’s challenge in European geopolitics

🔴 C. Raja Mohan writes: Greater engagement with Europe and dealing with its multiple contradictions must necessarily be important elements of India’s international relations today

The resignation of Germany’s naval chief, Vice Admiral Kay-Achim Schonbach, followed the uproar in Europe over his remarks about Russia, China and Ukraine.

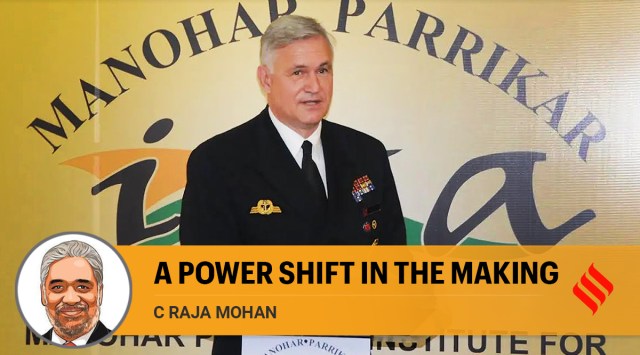

The resignation of Germany’s naval chief, Vice Admiral Kay-Achim Schonbach, followed the uproar in Europe over his remarks about Russia, China and Ukraine.It is unfortunate that the seven-month-long Indo-Pacific journey of the German frigate, FGS Bayern, ended with the resignation of Germany’s naval chief, Vice Admiral Kay-Achim Schonbach. He was in Delhi last week to mark Bayern’s port call in Mumbai. Schonbach’s resignation followed the uproar in Europe over his remarks about Russia, China and Ukraine.

The Schonbach episode reminds us of the complexity of European geopolitics that never conformed to Delhi’s binary view of the region inherited from the Cold War era. As Delhi elevates Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to a higher pedestal in the national pantheon, it is a good moment to reflect on India’s great power politics in the pre-independence era.

For India, an important strategic priority today is to rebalance the Indo-Pacific that has been destabilised by China’s assertiveness in the region. Delhi, however, recognises that this expansive challenge can’t be met by any one power, including the US. A larger European role in securing Asia therefore becomes critical.

To Indian ears, at least, Schonbach’s comments on the importance of Russia in balancing China, the case for respecting Putin, NATO’s difficulty in admitting Ukraine, and the impossibility of retaking Crimea from Russia, are all rooted in common sense.

That peace with Russia in Europe might be necessary for America to focus on Asia has been the key motivation, if implicit, behind President Joe Biden’s decision to intensify engagement with Vladimir Putin in the last few months. If his predecessors dismissed Russia as a declining power, Biden was prepared to take a more realistic view of Russia’s enduring weight in European geopolitics.

On the question of Ukraine’s membership of NATO, Schonbach was not off the mark. The US and its European allies have suggested that Kyiv’s membership is certainly not imminent; but they are unwilling to say Ukraine will “never” be admitted. (All this could, however, change if Russia invades Ukraine.)

The problem with Schonbach’s comments was that they were too clear. His error was in shredding the carefully crafted political ambiguities in German and European positions over Ukraine. A soldier’s plain talk is not always welcome in the world of diplomacy, especially in the middle of a major crisis.

The Ukraine crisis that compelled Schonbach to resign reveals four deeply rooted contradictions. First, Europe remains geopolitically unstable. None of the three European settlements of the 20th century — in 1919 after the First World War, in 1945 after the Second World War, and in 1991 after the Cold War — has endured.

Second is the difficulty of integrating Russia into a European order on mutually acceptable terms. Russia was part of the great power system in Europe through the 18th and 19th centuries. If the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution put Russia and the West at odds with each other, the collapse of the Soviet Union has not resolved the contradiction.

Third, the growing tension between the US and Europe. Since the Second World War, Europe has relied on the US for its security, but it never stopped resenting the American dominance over its geopolitics. The EU’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell, has repeatedly objected to the US and Russia deciding the future of Ukraine over European heads. French President Emmanuel Macron has demanded that Europe should collectively set out its own requirements for peace in Europe. But Russia does not take the EU seriously and is betting on negotiations with the US.

Finally, the idea that Europe must look after its own security dates back to Charles de Gaulle. But it remains an unrealised ambition. While the EU has become a powerful economic entity (with its $17 trillion GDP), it remains a weak security actor.

The ambition to construct a strong geopolitical personality for the EU is hobbled by divisions over the role of Russia and the US in the region as well as the historically rooted mutual suspicions among European states. This is compounded by the reluctance to spend more on defence and the inability to develop collective defence arrangements outside of NATO led by the US. States on the western periphery of Russia would prefer an American role in ensuring their security and are reluctant to buy into the idea of a European “strategic autonomy” from Washington.

All these contradictions get concentrated in Germany that has long been at the heart of European geopolitics. Viewed as the most loyal ally of the US until recently, Germany is now seen by some in the American establishment as pivoting away from Washington.

Whatever might be the outcome from the gathering conflict over Ukraine, these European contradictions are not going to disappear any time soon. In turn, they demand that Delhi discard its tendency to view the region through the “East versus West” binary. Delhi today could profitably take a leaf out of the book of the Indian national movement.

In the late 18th century, as European powers competed for influence in the subcontinent, many Indian princes sought to take advantage of the contradictions between Britain and France to preserve their independence. As Germany became a great power by the end of the 19th century, Indian revolutionaries turned to Berlin in the early 20th century to overthrow British rule.

Imperial Germany supported the formation of a nationalist government of India in Kabul in 1915 headed by Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh. As Soviet Russia became a champion of Asia’s liberation from European imperialism, the Indian communists were drawn to Moscow.

Eager to accelerate Indian independence during the Second World War, Netaji turned to Germany and Japan, the world’s newest great power. He formed a provisional government of India in Singapore in 1943 with Japan’s support and inspired millions of Indians in the subcontinent and the globally dispersed British empire to fight for independence.

The sharpening struggle for Indian independence, and more broadly the liberation of Asia between the two World Wars, inevitably involved exploiting the contradictions between different imperial powers. This was complicated, however, by rapid realignment among the major powers —friends became adversaries and enemies became allies. The Indian and Asian national movements were deeply divided in coping with the shifting great power dynamic.

The world enters a similar moment today that could rearrange relations between the US, UK, Europe, Russia, China and Japan. Delhi’s focus must be on leveraging them for national benefit where it can and insulating India from the negative effects where it must. Greater engagement with Europe and dealing with its multiple contradictions must necessarily be important elements of India’s international relations today.

This column first appeared in the print edition on January 25, 2022 under the title ‘A power shift in the making’. The writer is a contributing editor on international affairs for The Indian Express.

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05