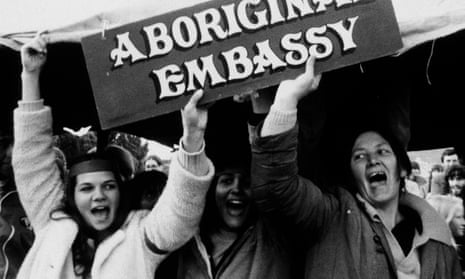

The great Australian protest documentary Ningla-A’na is returning to cinemas with a new restoration timed for the 50th anniversary of the film and its subject. Capturing the early days of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy – a hugely influential symbol of sovereignty that began as a beach umbrella erected by four activists (Billy Craigie, Tony Coorey, Michael Anderson and Bert Williams) in 1972 – it’s not just a historical document but a kind of evergreen clarion call and electric time capsule, burning with white-hot energy and a searing sense of purpose all these years later.

The launch of the Tent Embassy marked the first time many saw First Nations people confronting the establishment. In Ningla-A’na we watch protestors congregate, march, occupy public spaces and clash with cops, including in one shocking sequence that became a widely seen and highly influential depiction of police brutality. This moment, as curator Liz McNiven wrote for the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, “brought international attention to Aboriginal people’s struggle for land rights and human rights” and even “fundamentally changed the way the world saw Australia”.

Italian-born director Alessandro Cavadini structures the film – which was clearly made from inside the movement – around Indigenous voices. Given its message that black activists don’t need white spokespeople, it was an odd choice to open with an elderly white pacifist and former veteran, Jim Leacock, who comments about his life and attitudes towards war before finally moving on to the topic at hand, describing the push for Aboriginal land rights as “the most important direction we can take in helping to restore some of the injustice”.

But then Cavadini takes to the streets and never looks back, capturing many engaging subjects and the intense feeling and fervour of what would become a watershed moment in Australian history. The coolest subject is probably the great Gumbaynggirr activist and artist Gary Foley, who is what they call in documentary land “great talent” – a pull-no-punches presence who is loquacious, charismatic and mad as hell. After a tetchy exchange with a well-dressed white woman, Foley discusses the need for the black community to represent themselves, criticising previous iterations of the movement for being “full of white liberal shits” and arguing “people like her fucked our movement up for 20 years”.

Foley then responds to the suggestion that the movement may find more support from the wider community if he tones down his use of language. His retort is one for the ages. On the notion of obscenity: “You think that my language is obscene … I think that what is going on in the black communities in this country is obscene.” And on being offensive: “I find very, very, very offensive the fact that a black person in birth, if he sets one foot in a bloody thoroughfare, he will get his head kicked in … I find very offensive the highest infant mortality rate in the world in this country amongst black kids …. that’s offensive to me.”

Ningla-A’na’s restoration took seven months to complete, cost around $40,000 and received crowdfunding support from financiers including Russell Crowe. The rerelease will hopefully introduce it to a new generation and bestow upon the film its rightful status as Australia’s greatest ever protest movie: so alive and so galvanising it seems to have its own electromagnetic force.

There’s been some good protest documentaries in recent years (including The Tall Man, Defiant Lives, Brazen Hussies and Frackman) but nothing that registers with this sort of impact. And nothing that so vividly captures such a significant event in modern Australian history, when activists (among many other things) created, as Jennetta Quinn-Bates put it, “a deliberate reminder of the ongoing atrocities subjected to the oldest living culture on the planet” and a space where Indigenous people – in the words of Roxley Foley – can “heal something in themselves”.

Cavadini takes a multifaceted approach to exploring activism, digressing from tumultuous footage to quieter moments exploring topics such as the role of feminism within the movement, the birth of modern Indigenous theatre, and the shocking state of Indigenous health, articulated in a powerful sequence by Professor Fred Hollows. Cavadini went on to co-direct another historically significant documentary, Two Laws, which introduced many white Australians to the concept of this country having two kinds of laws, one of course existing far longer than the other.

With time maybe that production will also be restored and its presence renewed in the zeitgeist. For now all eyes should be on Ningla-A’na: the very definition of an unmissable Australian film, returning to the big screen like a clap of thunder.

Ningla-A’na is playing in select theatres around Australia

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion