Vanessa* is lying on what looks like a massage table wrapped in cling film. It’s hot and sticky against her skin. She’s trying to ignore the pain and looks up at the ceiling, at the artwork on the walls. Trying to think about anything but the needle, the burning sensation – and another uncomfortable feeling she’s only just starting to recognise.

She hadn’t been sure what to expect, she’d known the guy tattooing her, Sam*, was a big name in the industry – with thousands of Instagram followers. The tattoos he creates are works of art and just the style she wanted. She couldn’t believe it when he’d said yes to tattooing her, and in such an intimate area: on her chest.

At the first appointment, Sam had been flirty, but she’d batted off his comments with a nervous chuckle. He was being polite. Wasn’t he? But today, things have taken a turn. “I’ll do this tattoo for free, for a blowjob?” the words pour out sleazily, as the tattoo machine and its pinching needle is dragged across her exposed skin.

She tried to find the courage to say no, the word about to form on her tongue, but he didn’t wait for a response. He started touching her breasts, the next thing she knows, she can feel the full weight of him pressing on her. There’s no one in the studio, they’re alone. She’d felt safe at first, reassured by the fact that it was only the two of them, no prying eyes. Now she realises this empty studio is not for her benefit… there’s nothing she can do, no one to help her…

A lawless industry

This feeling of unease – and power imbalance – is prevalent not only in tattoo shops, but throughout the industry at large. Take tattoo conventions; once I watched a woman wearing a bikini, a crowd eagerly ogling her, as a man set about inking her ankle. Was the bikini really necessary? Was the poster hanging behind her, showing a naked woman, two men in balaclavas pinning her down, as she screams, necessary either? So often there's a toxic sort of male energy in the air, mixed with physically unwanted brushes up against my body and lingering stares.

A 1933 book by Albert Parry, Secrets of a Strange Art, likened getting tattooed to sex – the needle, he wrote, was a penis. And tattooed women were sluts who couldn’t possibly be virgins, Parry stated – and those attitudes became so deeply ingrained that they still play out today. Even when I first started getting tattooed, in 2007, tattooists were bound by an outdated "moral code": that they own the tattoo on your body, therefore have some say in what happens to it.

I remember in the noughties, before the days of Instagram, I’d gone into a newsagent seeking tattoo inspiration. I’d had to reach up to the top shelf to find the tattoo magazines sitting next to lad mags and porn. On the cover of one was a female tattooist, legs spread, breasts cupped in her hands. I’ve no problem with women owning their sexuality. But I do have a problem when the same isn’t expected from their male counterparts – and there’s no other alternative.

So in 2012, I launched a tattoo magazine for women. I wanted to make a change. I’d been collecting tattoos since I was 21, intricate designs working their way over my body. I’d fallen in love with how tattoos made me feel, but I didn’t love the tattoo world itself. Tattoo bros and lads reigned supreme. Women – our bodies – weren’t respected. My magazine was met with aggressive resistance: “we don’t need a magazine for women.” Only now do I realise it was the men who spat those comments at me who were abusing their positions of power. They were scared of being found out, that the lad culture that had kept them safe was at risk of being exposed.

These men, their attitudes, whirl around my mind as I settle into the public viewing gallery of court 13 inside the Royal Courts of Justice – the very same room in which the Depp v The Sun libel case unfolded. It’s February 2023 and sitting in front of me is tattooist Billy Hay. It’s surreal seeing him out of context, his tattooed neck and hands poking out of a stiff suit. Hay is a prominent figure in the industry, his face is familiar, he’s someone I see working at tattoo conventions regularly… But more than a decade ago, he violently sexually assaulted a woman named Nina Cresswell on a night out. It’s hard to fathom that I’m not about to watch his trial unfold. Instead, Hay is suing the woman he sexually assaulted for defamation...

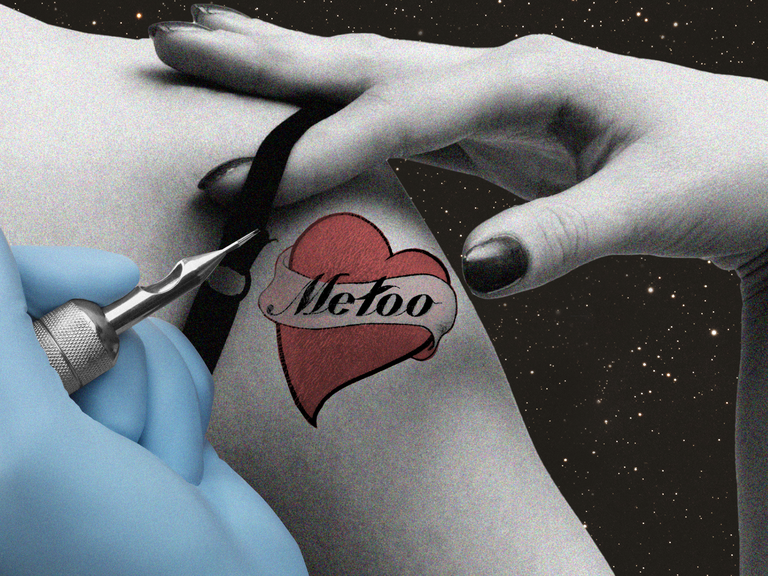

Me too enters the tattoo world

Glasgow-based tattoo artist, Fidjit, started naming alleged rapists and abusers on her Instagram account in 2015. The first she posted about was her own experience with a tattooist. With permission, she’d reshare stories from other survivors who’d experienced everything from being asked to remove clothes that they didn’t need to during appointments and being touched without consent, to violent assaults that left women with scars beyond that of the tattoo inked into their skin.

“I’ve got a lot of backlash for posting names,” she tells me. “Some people will still associate with a predator tattooer if they think it will benefit them, it’s disgusting.” Fast forward to 2020, during the dark days of the first lockdown and a revelatory #MeToo movement in the tattoo industry gained momentum (similar to one in the US in 2018, which was reported in Jezebel.) Fidjit – who has nearly 50k followers on Instagram – shared a story about one particular predator. Sam, who’d tattooed Vanessa.

Fidjit was unprepared for the avalanche of women who, emboldened by the fact that she had posted about him, felt able to share their stories. “It was overwhelming,” she says. Hundreds of women slid into Fidjit’s DMs, but it wasn’t just about this one tattooer, other names came up, too. Some over and over again.

“It was the first time such a huge amount of people really took notice of what was being said.” In turn, anonymous Instagram accounts – with handles such as Tattoo Me Too – started popping up naming sexual predators to warn people not to book in with them. “Speaking out, telling your story, it’s a way for survivors to take some power back,” says Fidjit.

Cresswell had never actually wanted to speak publicly about what William 'Billy' Hay did to her. But she’d been let down by the police when they’d recorded her assault as a “no crime” mere hours after it happened. She tried to bury it, move on with her life. But when more and more tattooists were being named, she knew she couldn’t stay quiet. She needed to warn other women who might end up under his needle… and so, in June 2020, she wrote about the night that Billy Hay attacked her in an anonymous blog post. She then shared it with his girlfriend and business partner – who she thought needed to know – before posting it to her Facebook and Instagram.

“There’s something empowering about sharing your experiences and having them validated by others, and for many women and girls, the words of support and encouragement are hugely beneficial,” says Jayne Butler, CEO of Rape Crisis. “When people speak publicly about their experiences it can help to destigmatise sexual violence and abuse and help others to feel less alone in their trauma.”

Before we continue, let’s make one thing clear: “if someone touched you sexually and you didn’t want that to happen, they have committed a criminal offence,” states Leigh Morgan, senior legal officer at frontline women’s legal rights charity, Rights of Women. And while we as women know that, the stark reality is that the highest ever number of rapes – 70,330 – was recorded in the year ending March 2022. But in that same period, just 2,223 cases were brought to charge. The most heartbreaking statistic is that 5 in 6 women who’ve been raped say they don’t report it to the police. “The police are famous for failing survivors,” says Fidjit.

Sam, for example, who assaulted Vanessa – and countless other women – was arrested after multiple women went to the police to report him, but the case collapsed due to a supposed lack of evidence and there’s rumours that he’s tattooing again, under a different name. And there’s Cresswell. Let down by the police when she needed them most. Then, just after she posted about Billy Hay she received an email from his lawyer stating that her account was a "work of fiction". And so, she was put on trial by the tattooist who attacked her.

But you do have the right to be taken seriously by the police and professionals, continues Morgan. “As a victim of a crime, you have a set of rights and minimum standard of support that organisations, such as the police, must provide to you – which is set out in the Victim’s Code.” (FYI, Rights of Women can also offer options when an abuser is not charged.)

“The system and the law are both flawed, from taking your statement all the way through to being in court. It doesn’t protect survivors, it protects scumbags,” asserts Fidjit. “That’s why we share our stories. When you post your own story, there’s no one to censor you.”

Where rape culture thrives

Until recently, there’s been no one to censor the predators in the tattoo world. It’s a mysterious sort of industry where you pay cash, there are no set rates and no one is up front about it until you ask. Like you don't deserve a tattoo if you need to know how much it costs. There are no HR departments or official training routes.

When Leah* started working as a tattoo artist at a famous London tattoo shop, she was delighted. It’s where all the celebs go – influencers, actors, musicians, Love Islanders... But what was portrayed on Instagram was very different to her reality. “The owners were nice to me at first, they’d buy me gifts and make me feel special,” she tells me. Looking back, she can see that it was part of the manipulation to keep everyone quiet, grooming them to make them work until they “burnt out.”

“I felt like I was treading on eggshells, I was extremely uncomfortable all the time,” says Leah. The power dynamics were all wrong in the shop, Leah explains. “[The owners] were always commenting on the way people's bodies looked, there were snarky comments about clients, prices were ridiculous.”

Another anonymous source confirms that often the price was changed while the client was actually getting tattooed. There’s multiple stories of women being told by the owner to strip to levels of undress that weren’t appropriate for the tattoo they were getting. The same source also told me that there was a hidden lingerie drawer for women who came in wearing underwear that wasn’t deemed “sexy” enough for the Instagram photos.

In another studio run by a male tattooist who’d regularly dish out free tattoos to underage girls (legally, you have to be 18 to get tattooed), photos were taken of clients in various states of undress without their consent. “I was tattooed by him on my wrist when I was 15,” Sarah* tells me. “I was on my own in a private room while I was getting my wrist done and he was very touchy, rubbing his leg against mine. I didn’t think anything of it, as I’d never been tattooed before.” The tattooist offered Sarah a full back tattoo in return for a “good time”, and told her to pop back in when nobody was there. “I declined and never went back.”

I first spoke with Cresswell just after that blog post was published. I’ll never forget how she described the tattoo world as an “insidious” place. We spent hours on the phone. In 2010, she was on a night out when she spotted her tattooist at the time, Richard 'Bez' Beston of Triple Six Studios. With Bez was Glasgow-based tattooist Billy Hay, who was doing a guest spot in his studio. He introduced Hay to Cresswell – and she trusted him, because she trusted Beston. It was on that night, on her way home from the club, that Hay sexually assaulted Cresswell.

In the hours following the attack, not only did Cresswell go to the police, but she also messaged Beston asking for help, naming Hay. The first words in his reply were 'ha ha', before failing to answer any of her questions about Hay's whereabouts that night. She then called Beston, and he told her he “didn't want to get involved”.

“That’s the problem,” Cresswell says. “So many in the tattoo industry put their fingers in their ears when it comes to predators. They either outright protect and defend them, or they 'don't want to get involved'. All they care about is their own reputation – the silence is so unsettling.”

And that’s exactly how predators continue to work in this industry.

A whisper network of survivor stories

Over the past three years, I’ve been collecting hundreds of stories from those who’ve experienced abuse at the hands of a tattooist (gut-wrenching stories that land in my inbox to this day, experiences I thought the Me Too movement might put a stop to). Many of the women decided against sharing their stories publicly – they didn’t want to be recognised or for their court cases to be put at risk.

Abuse has been like an open secret, behaviours brushed off with “oh that's just what he's like”. Women told they must be mistaken or that they asked for it in some way, and so predators continue to tattoo. They keep their jobs because it's just “lads being lads”. No one says anything but everyone knows who they are.

What played out in the courtroom between Cresswell and Hay is the epitome of what the tattoo world breeds. Hay stated that Cresswell was lying – and so he just expected to be believed. His witnesses – Beston and a fellow tattooist mate, Joe 'JJ' Jackson, who’s based in York – are complicit. I watched on as they continued to protect each other, insinuating that it’s actually men who can’t say anything anymore due to the “current climate.”

“This super supportive culture is good for nobody,” Jackson wrote in a WhatsApp that was used in evidence. “There is no reasoning. I feel like we (men) are trying to [be] reduced to below women (not equal rights), and this is just one of the steps to do it.” Jackson also suggested abuse allegations were being fabricated so that women could get free tattoos.

Throughout writing this piece, something else that kept coming up in my conversations was the fact that the tattoo industry is unregulated. “There’s so many blurred lines and states of undress, if you’ve never been tattooed you don’t know what to expect or where you’re going to be touched,” explains tattoo artist, Lucy, who set up Tsass_uk, a survivor-led safe space, after she’d opened up about her own experience at the hands of a male tattooist. “You’re nervous, you don’t know what to say, you feel like you can’t say anything if you’re uncomfortable.”

“In England, all you need is to be licensed by a local authority,” Lucy continues. “All that shows is that you’re hygienic, so basically anyone could get one. You could open a tattoo studio tomorrow even if you’ve never tattooed before. On top of that, there’s no background checking. No questions asked.” Lucy is campaigning for DBS checks to become a mandatory part of being a tattooist.

“If these industries were better regulated with bodies that worked toward better workplace cultures and dealt with sexual misconduct allegations appropriately, this would give victims alternative routes to justice and help ensure others are kept safe from perpetrators’ abuse,” adds Deeba Syed, senior legal officer at Rights of Women.

That said, others question whether this is the answer. “Tattooing being unregulated isn’t why these things happen. Tattooing doesn’t need more regulations,” asserts Fidjit. “Background checks don’t work because rapists and abusers very rarely have criminal convictions for rape and abuse. Barely any of the names who've been outed on social media have criminal records. An abuser will manipulate situations; they don’t stop because they have checks done, they work around that. Abusers still exist in heavily regulated industries. Authority constantly fails survivors.”

So what’s the answer? “Tattooers need to have a zero tolerance policy towards rapists,” says Fidjit. “Stop making excuses for these people if they work in your shop. Stop having them in your studio, stop letting them work your conventions, stop putting them in your magazines, stop promoting their work online, listen to survivors when they’re putting their neck on the line to warn you.”

And if you’re someone who wants to get tattooed? “There’s choices,” says Lucy, who suggests having a conversation with your artist before you book. “So you can build a rapport with them and see what kind of person they are. Explain you’re new to this and ask what you should expect. Even ask if you can bring a friend.”

Most importantly, remember that it’s not an honour to get someone’s work tattooed on your body, it’s their privilege to tattoo your skin. No one owns the tattoo on your body but you. If you didn’t have a good experience with someone, you can get another tattooist to finish it for you. Thousands of followers and verified blue ticks are meaningless – it’s about communication and feeling comfortable. Tattoo shops should be magical places, not somewhere you walk in and feel like you don’t belong.

* Name has been changed

** This article was originally published 16 January 2023 and was updated on 5 June 2023, after Nina Cresswell won the libel case against Billy Hay who tried to silence her in court. She can now say that he violently sexually assaulted her. The judge concluded that Cresswell was sexually assaulted and that she “has shown on the balance of probabilities that the perpetrator of the violent sexual assault upon her was the claimant”, Billy Hay. Cresswell’s defence was funded by The Good Law Project and her case has now been reopened by the police.

Alice set up Things & Ink to give a voice to women in the tattoo world

If you have been affected by any of the stories in this feature, contact Rape Crisis for support. Rights of Women can also provide vital legal support to women in England and Wales to help you to understand your rights and options, including sexual offences such as rape and sexual assault, reporting offences to the police and the criminal justice system, victims right to review scheme and criminal injuries compensation.

Alice is a freelance writer, editor and author of Tattoo Street Style. She's currently working with the features team at Cosmopolitan UK (across print and digital). She loves writing in long-form, and covers everything from issues and news affecting women to books, health, art and culture. When she's not working, she's probs watching reality TV, reading a book or out walking with her dog.