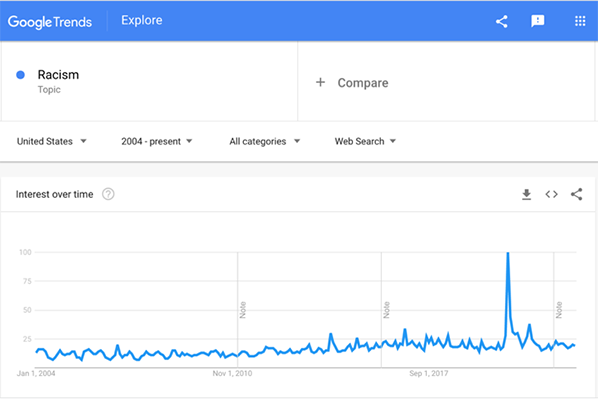

Racial divisions have become the stalking horse of our politics and social discourse, with racism defined as white on black (often extending to Western vs. non-Western ethnicities). Google Trends reveals how the online topic of racism has steadily risen over the past decade, spiking like a seismic reading of an earthquake in June, 2020 that marked the George Floyd tragedy and the Black Lives Matter protests that followed.

In due course we’ve been treated to a surfeit of acronyms to help us understand our racial divisions, from BLM and CRT to DEI, CSJ, and SEL.1

Our educational institutions have done their best to promote race consciousness in schools through books and pedagogic exercises defined by racial groupings. One teachers’ handbook promises to “equip students to engage with the most urgent issues of our time. With a groundbreaking intersectional approach framed around social spheres, Race in America gives students the tools to think critically about race, racism, and white privilege.”

This is not so much about learning history as promoting tribalism. The standing premise is that race dominates all identity classifications for explaining disparities among groups.

Certainly, anecdotal and systemic racism has played its part, but then again, unresolved debates over preferences, crime, constitutional challenges to Affirmative Action, self-segregation, and voting rights raise questions over whether the emphasis on race and its root in identity politics has advanced the cause of racial equality or has even been the determining factor of political, social, and economic outcomes. After a century of post-bellum struggles and breakthroughs during the civil rights era, it would appear we are now moving farther away from the ideal of Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of a color-blind society.

The current Supreme Court case on redistricting in Alabama under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is an illustrative case. The VRA was instituted as part of the defense of civil rights to protect the right to vote for minority groups by prohibiting race as the basis of electoral rules. We see the unintended result in gerrymandered minority districts that create higher shares of black voters electing black representatives. But this not only violates the spirit of the VRA, it promotes self-segregation, creating the separation of races the policy is seeking to integrate.

In two other SCOTUS cases, a student advocate group is suing Harvard University and the University of North Carolina over race-based admissions policies. And most recently, the scandal involving racial and ethnic battles on the Los Angeles City Council has exposed the fragility of a race-based political coalition based on a unified community of “persons of color.”

The underlying assumption that DNA determines outcomes is at the heart of the problem. It assumes that group interests can only be justly represented by members of that same identity group and all groups must be represented in proportion to their share of the population. Anything less is racist. So, blacks must elect black representatives, Hispanics for Hispanics, Asians for Asians, etc. If our goal is integration and assimilation to achieve race-blind outcomes, this trend inevitably sets us back.

Why Race?

We should accept that the issue of race in America is confounded by the historical legacy of the African slave trade. Such anti-black racism was institutionalized for much of our history with slavery followed by Jim Crow laws and forced segregation up until the 1960s. In more recent times we have witnessed highly publicized racial altercations with law enforcement associated with the Rodney King, OJ Simpson, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor incidents. We hit the tipping point with the tragic case of George Floyd.

We cannot dismiss such shocking events, but the boiling outrage obscures how infrequently such racist acts occur in today’s America. So infrequently that some racialists feel the need to create them. In his book, Hate Crime Hoax, Wilfred Reilly (a black scholar) documents a dataset of 409 allegedly false or dubious hate crime allegations (concentrated during the past five years), which he describes as hoaxes on the basis of reports in mainstream national or regional news sources. These hoaxes attempt to bolster the indefensible racist narrative.

Undeterred by the evidence, racialists have shifted focus in recent years from explicit racism to incontestable systemic racism. Their logic now argues that mathematics and science are racist. Time management is racist. Speaking grammatically correct English is racist. Wearing a tie is racist. We have gone from proving discrimination through legal means to suggesting disparate outcomes have racist causes (which is social science in reverse). This permits racialists not only to condemn oppressors who don’t even know they are oppressors, but also allows them to pose as virtuous, anti-racist, social justice warriors.2

After electing Barack Obama in 2008 and again in 2012, this reversal in race relations has taken most Americans by surprise.

Culture and Multiculturalism

During and after the civil rights movement there was a radical shift in urban black communities that promoted a unique American black culture that rejected those attributes of the “white” mainstream. This was marked by the split between MLK Jr. and Malcolm X, followed by the Black Panthers and Nation of Islam.

One problem with the “Afro-centric” formulation is that capitalism—in Asia, Africa or the Middle East—rewards and reinforces cultural behaviors that Max Weber labelled as the (European) Protestant Work Ethic.

The key dynamic in capitalism is wealth building through capital accumulation that results from saving and investing in both financial and human capital (education). A culture or subculture that eschews saving and investing while encouraging over-consumption cannot benefit from the virtuous cycle of compounding wealth. Though pejoratively labelled “acting white,” these formulas for success are not racial or ethnic, they are cultural and can be adopted by any individual or population. The Jewish diaspora has long embraced these cultural attributes in response to their own segregation from Christian Europe. Admittedly, parsimony is not a virtue promoted by a market system pushing conspicuous consumption as a symbol for status and meaning.

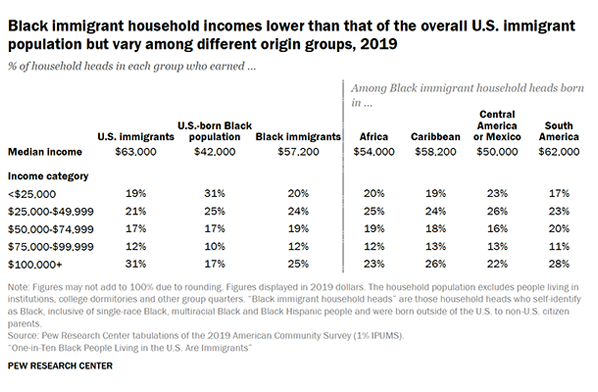

South Asian immigrants, of every shade of skin color, are another example: after barely two generations, South Asians as a group have the highest household median income in the US, followed by Taiwanese and Filipinos. One can make a distinction for African heritage, but black immigrant groups from Africa and the Americas also outperform in educational achievement, employment, and household incomes.3

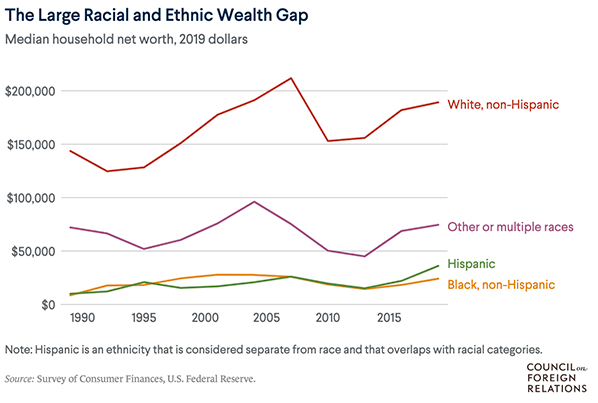

In the past many American blacks were prohibited from accumulating capital and real assets under the systemic racism of the past, so they have been disadvantaged generationally. This can explain some of the racial disparity in wealth accumulation and why racial wealth gaps are far greater than income gaps. But the solution is not decrying racism of the past, rather we should adopt the dominant cultural formula for success regardless of race, creed, gender, or ethnicity.

Today’s racial narrative is often labeled cultural Marxism or racial Marxism. Marxist ideology is based on class divisions between capital and labor. Unfortunately for Marxist ideologues, class divisions have so far failed to solidify durable political coalitions in the US, even during the depression era. Americans see themselves as upwardly mobile, so class warfare has never been widely embraced.

In contrast, identity and especially race have proven far more potent as a political wedge necessary to a kind of faux “Marxist” agenda, particularly in the ideological hothouses of the media and the University. Rather than the class struggle, culture wars have come to define US political divisions since the 1970s and the purpose is disruptive. Today, the racist narrative has sadly become the most powerful identity marker because in political context, anti-racism is power. But this power play only serves to obscure the true dynamics of our political and economic divides.

The True Divide: Class

When we unpack inequality in the constellation of political and economic power, class division between capital and labor has historically been the most significant factor. Marx was correct (as he noted in Das Kapital, updated by Thomas Piketty with Capital), that capital concentrates success, while the market dynamic to maximize profits often depresses wage incomes relative to capital incomes. The capitalist principle that “money makes money” drives a wedge between those who have it and those who do not, creating our American class tensions between rich, middle class, and poor. This wedge has been widening persistently with the financial and fiscal policies of recent decades dangerously hollowing out the middle class.

Pew Research data show that the richest families in the U.S. have experienced greater gains in wealth than other families in recent decades, a trend that reinforces the growing concentration of financial resources at the top.4 Another study by the Council on Foreign Relations notes that in 2021, the top 10 percent of Americans held nearly 70 percent of U.S. wealth, up from about 61 percent at the end of 1989.5 The share held by the next 40 percent fell correspondingly over that period. The bottom 50 percent (roughly sixty-three million families) owned about 2.5 percent of wealth in 2021. This widening of the wealth gap has roiled our national politics may be seen as disproportionately impactful on particular races, but exists as well within racial groups. There are rich blacks, and poor Asians and Jews, while, in sheer numbers there are more white people living in poverty than any other group.6

We certainly cannot absolve slavery and racism. As previously stated, American blacks and other poor minority groups have been historically disadvantaged from accumulating capital assets. That fact explains much of the differences between income and wealth disparities, holding other significant factors such as education constant. But in searching for solutions we need to keep in mind that chattel slavery as practiced in the pre-bellum South was as much about property and forced labor as a means of production on plantations as it was about the racial identity of the slaves. In material terms, slavery was an economic class phenomenon.

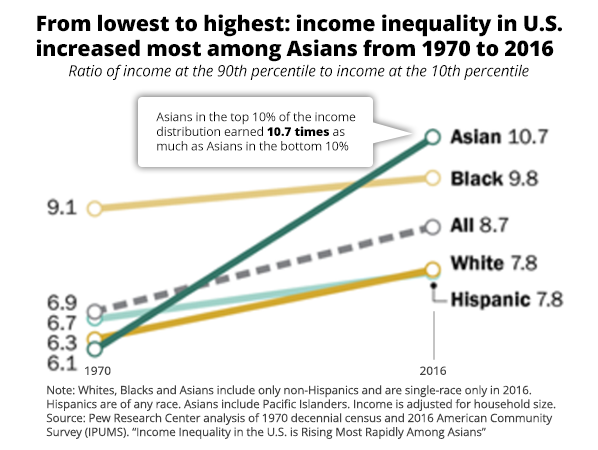

Further evidence that racism is not the primary driver of inequality in today’s America is illustrated by the experience of Asian immigrants and by the changes in income inequality over time within racial groups, especially among Asians. The median net worth of Asian Americans in 2019 was $156,000, placing them close to that of native white Americans.7 But the accompanying data from Pew Research shows that over the past 45 years growing inequality among Asians far outpaces other groups and that inequality among blacks is higher and rising faster than both whites and Hispanics.8 Racism cannot explain these trends within groups.9

A Cultural Correction

If we want to address the critical issue of economic inequality, the solution must be found elsewhere than in race and identity politics. In other words, it’s not about who you are as much as about what you do.

The widespread accusations of racist policing can help illustrate divergent cultural norms among minorities, especially for young black males. It starts with the breakdown of two-parent families under the well-meaning welfare policies of the Great Society programs. Economist Thomas Sowell has done excellent research documenting the disintegration of black families after the 1960s.

This problem has been compounded by the decline in public school education under the urban political machine that has repurposed resources in response to political pressures, mostly from public unions. Without strong parental role models and inadequate educational opportunities, young urban minorities face few lucrative employment or career prospects, so where else to turn except to the highly lucrative drug trade? When the violent criminality of the drug trade becomes a political liability, the same urban political machine turns to law enforcement and the criminal justice system to solve the problem. Naturally this leads to far more direct altercations between police and urban minority males, increasing the inevitability of highly publicized human tragedies (these incidents harm victims and police, as well as alleged perpetrators).

The thread of causation from poor, broken families to educational disadvantages to underemployment to criminal activity to police confrontations to unintended tragedies is fairly straightforward. We won’t fix anything for urban minorities if we don’t break this vicious spiral.

Furthermore, mischaracterizing our inequality as primarily racist has been bundled up with a stew of “woke-ism” that uses race and gender as the chosen identity markers rather than trying to create new, and broader, access to economic opportunity and advancement.

As Rev. King preached, we will need to get beyond race to discover who we are as a human community. The recent racial and cultural trend toward tribalism in Western societies is a step backwards and is not going to bring us to the Promised Land.

Michael Harrington is a political scientist, policy analyst, writer, and former resident of Los Angeles now living in Charleston, South Carolina. He blogs at Casino Capitalism and Crapshoot Politics, mharrington.substack.com/ and tukaglobal.com.

1 Black Lives Matter; Critical Race Theory; Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Campaign for Social Justice; Social Emotional Learning.

2 “Virtue Signaling, Implicit Bias, and the Recent Black Lives Matter Movement”, “The Myth of Systemic Police Racism”

3 “Key findings about Black immigrants in the U.S.”, “Study Shows African Immigrants in US Do Well, Despite Differences Among Them”, “Household income, poverty status and home ownership among Black immigrants”.

4 “Trends in Income and Wealth Inequality”

5 “The U.S. Inequality Debate”

6 “Poverty rate in the United States in 2021, by ethnic group”

7 “Many U.S. Households Do Not Have Biggest Contributors to Wealth: Home Equity and Retirement Accounts”

8 “Income Inequality in the U.S. Is Rising Most Rapidly Among Asians”

9 “Why income inequality is growing at the fastest rate among Asian Americans”