I can hear music from the bar two doors down spilling out into the street. After-work-drinkers and night-out-on-the-towners gather in the smoking area as more line up to get inside. I’m watching them from where I’m standing in a disused alcove, surrounded by a sea of high-vis jackets, listening to Inspector Andy Durrant give his night-time briefing to the few dozen officers who – from 9pm until the early hours this bustling Friday night in Shoreditch – have one job, and one job only, to help keep women safe. Across London, other units, in other boroughs, are doing the same thing.

Tonight, I’m joining them on this particular beat, as I want to know: how can the police protect women when, put quite simply, we don’t trust them? It’s almost two years to the day since the murder of Sarah Everard. We all, of course, know the story. How she was kidnapped, raped and murdered by a serving Metropolitan Police officer, Wayne Couzens. But Couzens is far from just one "bad apple" – and this tragic case is an example of a long and brutal history of police corruption.

In June 2022, two Met officers were sentenced to 33 months in prison after sharing photos of the bodies of Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, who were murdered in a north-west London park on 6 June 2020. And in January 2023, Met officer David Carrick was outed as a serial rapist. Carrick pleaded guilty to 49 offences – including 20 counts of rape – against 12 women, prompting Met commissioner Sir Mark Rowley to reveal that the force is currently investigating 1,000 sexual and domestic abuse claims involving about 800 of its officers.

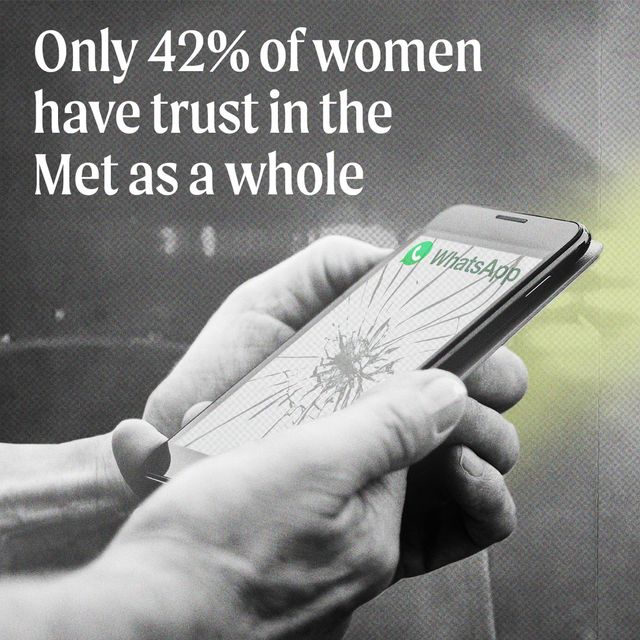

So far, so rotten. For many, faith and trust in the police has been rapidly declining since the murder of Everard. Recent statistics from YouGov show that only 42% of women have trust in the Met as a whole, while just 41% of women trust individual officers. The figures are even lower for ethnic minority Londoners, only 37% of whom trust the Met Police force.

This is against the backdrop of what the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, describes as “an epidemic of violence against women.” According to the latest figures from the Counting Dead Women project, at least 144 women in the UK were killed by men (or where a man was the principal suspect) in 2021. In 2022, this figure dropped slightly to 107.

Of these victims, there are the names you’ll recognise – Sabina Nessa, Ashling Murphy, Zara Aleena. But there are many you won’t, whose names haven’t dominated headlines.

Domestic abuse is also on the rise. Figures from the Office for National Statistics in March 2022 show that domestic abuse-related crimes were 7.7% higher than the previous year, and 14.1% higher than the year before that. Although, these figures can never truly paint the full picture, given that so many domestic abuse cases go unreported.

To end violence against women, prevention and support services for domestic abuse are desperately needed, but we also need a strong and solid police force, who we can trust to help us when we need them. The Met insists that we do have that, and the force has set up an array of initiatives to tackle violence against women: both internally and externally. But, is this enough? I joined the Met, over a series of days and nights, to find out…

Ally or enemy?

They spotted her just in time. The young woman, her head swaying and her legs flailing beneath her, being led by a much steadier looking man. He had his arm around her, guiding her towards an unmarked car posing as a taxi outside a kebab shop. “It was one of those hybrid-type cars. You know, the ones that Uber drivers tend to have,” Inspector Durrant recalls, proudly telling me how his officers stepped in and arrested the man, who’s still being investigated.

This is just one of the many scenarios that Durrant describes on our night in Shoreditch, as I tag along on Project Vigilant – one of the Met’s newer initiatives to tackle violence against women.

It was set up in 2021 to identify, prevent and deter predatory behaviour in the night-time economy. The scheme, which runs on Friday and Saturday nights, sees uniformed officers team up with specially trained plain-clothed officers to patrol the streets in search of anyone who may be displaying predatory behaviour. If a situation arises, plain-clothed officers alert their uniformed colleagues – like those I’m tagging along with tonight – who step in and engage with the concerned individual, taking any action required. This could be handing out a dispersal notice, requiring the individual to leave the area for a certain amount of time, or an arrest if a suspected crime has been committed.

"Relaxing shouldn't come at a cost,” Durrant tells me as we walk the streets together. He’s wearing his police uniform, complete with a hat and polished shoes. He’s tall, but not intimidating, telling me stories about his two young daughters in the brief moments of silence between us. As we speak his eyes dart from mine to those around us, he’s always on the lookout for anything suspicious. “Women should be able to enjoy themselves and let their guard down,” he says. It’s a statement we can all agree on, but the women I meet out in Shoreditch that night share the same concern.

“They’re the predators, that’s the problem,” one woman says when I approach her to find out what she thinks of the Met’s Project Vigilant. Her friend agrees, telling me that if she found herself in a vulnerable situation she wouldn’t “trust” a male officer to help her. Another woman said that while she was confident the presence of uniformed officers would deter members of the public from acting inappropriately towards women, she’s still “scared” of male police officers and would only approach one as a last resort. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all of the women I spoke to had no doubts about whether they’d feel safe around a female officer.

When I tell Durrant about what these women have honestly shared with me, he’s disappointed but not surprised. “We know there’s a challenge,” he says, before adding that the Met is doing its best to “project the positives” of its work in an effort to regain the trust of women. “If we take that out onto the streets and show people what we’re doing and what we’ve achieved, that will bring them back to us.”

Sarah walked these streets

It’s early on a cold February morning in Clapham. Commuters are packing into buses, hands clasped around hot coffees. A few of them eye me up and down. Usually I’d wonder why. Something on my face, perhaps? Has the zipper on my jeans come undone? Today, there’s no need for such questions, I know the reason for every glance. I’m walking alongside Police Constable Paterson, she says she’s used to being on the receiving end of these looks. Many of them unfavourable.

Paterson and I are spending the morning together, pacing the streets of Clapham: the very same streets that Everard was kidnapped from, and later, where women came to protest her murder. Just hours before it was due to go ahead, an official vigil organised by Reclaim These Streets was shut down, but thousands of mourners flocked to Clapham Common nonetheless. What was a peaceful gathering to remember Everard quickly turned sour with the growing number of Met officers on the scene and things descended into chaos – something which the Met was heavily criticised for. Several arrests were made at the vigil, with six of those in attendance charged for allegedly breaching COVID-19 restrictions, although these charges were later dropped by the Crown Prosecution Service.

Not far from where this all happened, I’ve joined Paterson on the Met’s Walk and Talk scheme, another avenue that the force hopes will build trust in its officers again. After registering online, women can buddy up with local female officers and walk them through an area they don’t feel safe in, sharing concerns about safety and discussing what needs to be done to alleviate these.

Paterson, whose dark hair peeks out from under her hat, sheds some light on the positive impacts the scheme has had so far, such as the instalment of CCTV in a problem area. She also tells me how the scheme offers a chance for officers to highlight what’s being put in place to protect women, such as the Clapham Hub – a safe space open on Friday and Saturday nights which offers first aid and a place to charge your phone or wait for a taxi.

But, in order for these solutions to come about, officers need to be made aware of the issues affecting women. It’s something that Paterson says isn’t happening, telling me that not enough women are utilising the Walk and Talk scheme, so their voices aren’t being heard. In part, she says, this is down to a lack of awareness that schemes like this exist.

After my time with Paterson, I polled Cosmopolitan UK readers on Instagram and found that only 5% of you were aware of the Walk and Talk scheme. But is it really on us to point out where problems lie? If the scheme relies on women to speak up, and fails when we don’t, that feels slightly like victim blaming to me. And isn’t it a bit of a misdirect, when the majority of crimes against women are carried out by men they know? The most recent figures from the Femicide Census show that only 8% of women died at the hands of a stranger, compared to 52% who were murdered by a current or former partner.

Although the issue is quite clearly them (being men), not us, it seems that women are willing to take part in the Walk and Talk scheme if there’s a chance it could improve our safety. Of the readers I polled, 71% said they’d be keen to go on a Walk and Talk, with one saying: “In order for stuff to change, you have to speak up and participate.” Another replied, “I want to do more to help women, so I would speak up.”

Not everyone was convinced however. “Unfortunately, due to the recent issues with the Met highlighted by the media, I don’t trust them,” said one respondent to the poll, as someone else wrote, “My concern is being alone with police.” Another Cosmopolitan UK reader replied: “Dark alleyways aren’t the problem. Police-perpetrated violence is.”

It’s a sentiment shared by the women’s campaign group, End Violence Against Women (EVAW). Director of the coalition, Andrea Simon, describes the Walk and Talk scheme as “poorly considered and fundamentally limiting” because it is “disproportionately taken up by women who feel more able to trust the police, therefore limiting its reach and amplifying inequalities in whose views are heard and inform policing responses to VAWG.”

When I head to New Scotland Yard to meet with the Met’s Assistant Commissioner Louisa Rolfe, I put to her the concerns about the Walk and Talk scheme. “We know we don’t have all of the answers,” Rolfe admits, adding that she welcomes this kind of feedback, be it “constructive criticism” or – in some cases – “constructive anger”.

Rolfe says the Met is aware of, and is proactively trying to break down, the barriers in place when it comes to hearing from “harder to reach communities”. She explains that, for those women not comfortable with attending a Walk and Talk or even engaging with officers directly, their voices can still be heard through online surveys that are regularly sent out. Rolfe is also keen to strengthen relationships with women’s organisations who can help bridge the gap between the Met and those less trusting of the force.

It’s going to get worse before it gets better

Two years on from Everard’s murder, the Met – unsurprisingly – wants to show how it’s changed. I was hardly going to be sent out on patrol with the kind of officers the force is trying to root out. But have these officers simply been banished to desk duty, swept under the rug and erased from the Met’s attempt at a squeaky-clean image?

Critics, it seems, agree that might be the case. They argue that the proactive measures the Met has taken to reduce violence against women within the community are merely surface level, and that the issue must first be tackled from the inside out. EVAW’s Simon brands the Met’s response to the issue of violence against women as “superficial” and tells me that “the gravity of police-perpetrated abuse” has not been appropriately addressed. “In order to be meaningful, the response from the police must start by confronting and addressing the systemic cultures of misogyny and racism within its own ranks.”

With this in mind, I go to meet Detective Chief Superintendent Tara McGovern, who runs the Met’s Anti-Corruption and Abuse Hotline. The hotline was set up last year and provides members of the public and officers themselves an outlet to report those at the Met who are corrupt and abusive, thereby undermining the Met’s integrity and letting Londoners down.

“Devastating,” is the response I get from McGovern when I ask her what it’s like hearing calls come into the hotline. “It's really very unpleasant,” she adds, explaining that – as hard as it may be for some officers to report a colleague – it has to be done. “When you’ve got predatory behaviour and you turn a blind eye to that, the perpetrator becomes further emboldened,” she says. “It’s corrosive.”

McGovern tells me that every call is listened to and assessed as either being a ‘conduct’ issue or a ‘criminal’ case. Cases are then passed onto the relevant investigation teams, such as DASO, the Met’s Domestic Abuse and Sexual Offences team. Once a case has been investigated, a public hearing is held to determine the outcome, which is made by an independent panel. In the most serious cases, the desired outcome is suspension (and perhaps criminal prosecution), but McGovern says frustratingly that: “the bar for an investigation is low, but the bar to suspend someone is high.” This sometimes results in officers retaining their posts when they most certainly shouldn’t, and why the Met is currently working with the Home Office to simplify the dismissal process.

Although the hotline has not been running long enough to provide tangible statistics on its success at weeding out the bad apples (suspension cases can take upwards of 12 months), McGovern says it is “money well spent in tackling the issue”. But, she warns that things will get worse before they get better and that cases like Couzens and Carrick are just the beginning.

McGovern shares her concern that as more and more corrupt figures are uncovered – thanks to the Met’s revised focus on vetting (more on that in a minute) and reporting procedures – this will chip away at what little trust women have left in the force, especially when every bad apple makes front page news.

“There has been a failure to identify textbook patterns of offending by those departments responsible for police standards and vetting,” EVAW’s Simon says. “For women to have the trust and confidence to report violence and abuse to the police, we have to know that the institution doesn’t harbour perpetrators and takes every step to root out individuals who don’t belong in the police service.”

In response to Simon’s comment, Rolfe admits there have been shortfallings. “We’ve identified that whilst the Met has been adhering to national standards [when it comes to vetting], we haven’t always been as rigorous in re-vetting,” she says, explaining that re-vetting should happen at regular intervals, which the Met has failed to keep up with. Rolfe tells me that re-vetting all officers is now a priority, along with introducing extra layers of checks, increased supervision throughout an officer’s career and, importantly, instilling a zero tolerance approach to misogyny within the force, therefore empowering officers to call out this behaviour when they see it.

“It's not political correctness gone nuts,” McGovern adds of the Met’s crackdown on misogyny. “We're not saying you can’t have a sense of humour. It’s not about that. It’s about creating an environment where those predatory individuals cannot thrive, where they cannot operate. This will be the solution to our current predicament.”

The question of trust

I’m in the press room at New Scotland Yard. I’ve seen it on TV countless times. Officers usually sit behind the big desk at the far end of the room, cameras flashing in their faces as they appeal to the public for information. It’s much quieter in here today as I sit alone with the Met’s Assistant Commissioner, Louisa Rolfe. She’s about to cry, I can hear it in her voice. Then I see her look up, fixing her eyes on the ceiling – a tactic I often use when I’m trying to stop tears falling from my eyes. “I felt physically sick,” she says, recalling the moment she found out that a serving Met officer had been the one to take Everard’s life.

She points out that predators like Couzens and Carrick are attracted to policing because of the power these roles hold. “The wonderful thing about being a police officer is that you can make a difference every day, and you can make a difference to people who are in desperate circumstances,” she tells me. “But the sad reality is that, in a job that offers people the opportunity to be a hero, that will attract a minority of people who are in it for the wrong reasons.”

I ask her if she thinks that, after what happened to Everard, the Met can ever regain women’s trust. “We must,” she says with conviction.

“And there are many ways we must do that,” Rolfe adds. “One is through our everyday interactions with women, whether those women are victims of crime or if they just see police officers patrolling the streets. If what they see of policing and their interactions with officers is positive, then that will make a difference.” She emphasises that another integral element is “demonstrating that we take violence against women really seriously,” which she hopes can be achieved through “improving outcomes for victims of domestic abuse or sexual offences, as well as harmful practices, like female genital mutilation.”

Rolfe also acknowledges that a lot of work must be done to undo generational distrust in the police force – a topic that requires a 2,000-word feature of its own to unpack. In 1999, the Macpherson report found that the Metropolitan police was institutionally racist (meaning: they failed to give an appropriate service to some groups in society because of their colour, culture or ethnicity) and three decades on, it seems that the feeling remains. YouGov figures show that as of January 2023, 46% of people still think the Met is institutionally racist. There are issues when it comes to homophobia too. A report from the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) last year found that discrimination – including homophobic slurs – was often dismissed by officers as “friendly banter”.

Commenting on claims that the Met needs a “root and branch” review, Rolfe says this would be a distraction rather than a solution. “We need to be really open about what we are doing to reform… [but] let’s not get consumed by a process of reorganisation or pulling things apart for the sake of a symbolic ‘ta-da it’s different’,” she argues. “Actually, let’s do meaningful things that we know will make a difference.”

Is the work being done?

Like many across the capital – and it’s worth reiterating that this issue is, of course, not exclusive to London, but that violence against women is a nationwide (and global) issue – I’ve questioned my relationship with the police in light of Everard’s murder, something which I know is a privilege to only recently have had to do.

This relationship has been undeniably damaged and although we don’t yet know when – or if – it can ever be rectified, I do think that the Met is putting in the work to ensure we get there, or at least some of the way. The work being done by McGovern and those on the Anti-Corruption and Abuse Hotline seems promising, and schemes like Project Vigilant are a step in the right direction. Others, like the Walk and Talk – which in my opinion puts too much onus on women to drive change – could do with a rethink.

As I tagged along on each of these schemes, I met the officers working behind them – Rolfe, McGovern, Durrant and Paterson – as individuals, each with their own purposes and passions. Couzens and Carrick are individuals too – ones with their own motives and immoralities. But we must zoom out from the individuals. The issue, two years on from Everard's murder, remains institutional and systemic.

Ultimately, the Met cannot change, until society changes. Until individuals like Couzens and Carrick no longer exist. Until their ideologies, their beliefs, their hatred of women is stamped out. Misogyny must end. It must be broken down to its very foundations. We need more (and mandatory) training in schools and workplaces, as well as the police force. We need more regulation online. We need more protests, more voices. We need more men calling out men.

Echoing what feminists, activists and grassroots organisations have been saying – yelling – for a long time, McGovern said it perfectly: we need to create "an environment where those predatory individuals cannot thrive". Because there is no place for predatory behaviour. In the Met. In London. In the world.

If you have information about a police officer or member of Met staff who you believe is corrupt and/or abusing their position of power, call the Anti-Corruption and Abuse Hotline on 0800 085 0000.

Follow Jade on Instagram and Twitter.

Jade Biggs (she/her) is Cosmopolitan UK's Features Writer, covering everything from breaking news and latest royal gossip, to the health and fitness trends taking over your TikTok feed. She also works on first-person features and investigative long-reads, taking a deep-dive into mental health, celebrity culture and women's rights. Jade has been a journalist and content writer for ten years, and has interviewed leading researchers and doctors, high-profile influencers and fitness experts. She is a cat mum to four fur babies and is obsessed with Drag Race, bottomless brunches and wearing clothes only suitable for Bratz dolls. Follow her on Instagram or Twitter.